The Back of His Head (40 page)

Read The Back of His Head Online

Authors: Patrick Evans

A quick check at the window shows the woman down at the wheelchair, tilting it back towards herself and turning it as she speaks silently down to the small child it half-encloses. The wind bounces in her dark, springy hair. Sunshine, bleaching the sky, creating a democracy of little white clouds that puff across it.

I come down to her from the house, behind the tourists returning to the tour bus, whose driver still slumps resignedly against his wheel. I watch them yack and scramble their way aboard. Down on the road, cars start up. I wave at the bus as the engine fires. Some wave back.

The woman is pushing her child up the lawn towards me in his wheelchair, a large plastic cocoon that contains him in a web of straps. The boy crouches like a little spider in its web.

âThis is Anaru,' his mother tells me.

He stares up at my face, querulously, like a little old man.

Now he holds up to me the thing he's been moving through the air while left to himself down here. A model plane, a finger-span long, a jet fighterâ

âI brought him to meet you,' his mother says. âI wanted you to see him.'

âI'm going to be a fighter pilot,' the boy tells me.

I look at her. âYou're Jennifer.'

âYes. I've been here two or three times. But it's always been someone else taking the tour. I kept coming back till it was you.'

âWhy me?

âYou wrote the letter. You sent me the same letter twice.' No rancour, just a simple observation. She has one hand on the chair, and looks out across the city, and the wind moves her hair. âI wanted to see how he lived. How a famous writer lived.' Now she looks up at the house. âIt's not great but it seemed pretty good inside. All that furniture.'

âIt's not all what it seems to be. We had a valuation recently and sold some.'

âYou can tell when people let things go. They don't have to prove anything. Old money. I got angry when I saw it. The money.'

âThere's not that much there, really.'

She stares at me. âYes, there is. You don't understand. Of

course

there is. When I saw it the first time, I thoughtâI can't say it in front of the boy. I thought,

stuff you

, and I took the ashtray. I didn't want it to be something big so I took the ashtray. After I got the first letter. To get even.'

Down below, the little boy is whizzing his plane through the air and providing the sound effects.

âAnd then I thought, this is silly, it doesn't mean anything, I'll bring it backâanyway, I don't want anything of his.'

âWe really don't have money to give away, Jennifer. What we raise we spend on the Residence.'

âThat's what I mean,' she says. She's unlocking the straps, she's releasing the boy. âI want you to see him,' she says.

âCan he stand on his own?'

âSort of. He's pretty good, actually. Aren't you, boy?'

The child comes out of his cradle.

âI don't care about the money.' She bends down to him: he teeters between her palms. âBut you need to see him.'

Ah. To

see

him. My stomach knots up. I swallow hard. âRight.'

She holds him with one hand and pulls at his T-shirt with the other. âNo, Mum,' he says.

âMr Lawrence is going to be a friend of ours, boy.'

âPlease, Mum.'

âJust for a second.' She lifts up the back of his little shirt. âThereâ'

âAh.' And I peer down at him, at last. âYes. Yesâ'

It takes a few seconds, and then she begins to put him together again. When she's done, she leans forward and presses her face into the top of his head and holds him close. Soon his hand brings the plane up again.

âGood boy,' she says. âGood boy.'

I watch as she holds him up, across the lawn: his tiny, strutting body, his strange, man-in-the-moon profile. It occurs to me that he may be eight or nine years old, possibly more.

She walks him, and he flies the plane. I watch.

After a minute I suggest we take him for a ride on the old elevator. She puts him back in his chair, and we bring him into the garden room.

Now the chair is on the platform, with the two of us on either side. I flick the switch and the elevator begins to rise, with its familiar, low, urgent hum.

The boy holds the plane up, to rise into the air with the elevator.

I turn to the woman, across and above the boy's head and the weaving, ducking fighter. As we rise into the Residence, I feel as if I'm beginning to understand what's happening.

The boy looks up at me. âI'm going to be a fighter pilot,' he tells me.

I

think

I'm beginning to understand.

Far out on the plain, in a slight depression in the ground, Hamilton found ruined walls and a crumbling mausoleum that had a narrow, high dome. Bou Saada. He could see an old Ottoman bordj farther up behind it on a stony mound of earth. Its split walls were patched with ancient, furred whitewash. Nearby, figtrees, stunted, around a fountain whose sanguine water trickled into a canal lined with red and white piles of saltpetre and salt.

In the bordj he was given a small room that had a reed mat, a chest of drawers and a skin of water hanging from a nail. There were Fez cushions in embroidered leather and the walls were painted white. Lying on the mat he sensed the old building hulked around him in silence, though sometimes a fettered horse whinnied outside, or there was the passing thud of hooves and, regularly, the squeaking of a bucket being let down into a well and pulled out again. Less frequently and from farther away, the low, savage growl of the camels when they arrived to kneel at the gate. All this as evening set in.

That was when he remembered the tangerine in his pocket and took it out and peeled it, and pushed the sweet pulp of it hard against his teeth and palate till it broke and dissolved into juice. He began to think of the boy again.

Back at the military camp he'd been told he came from here, from Bou Saada, though everyone knew the coastal Arabs despised the Amazigh youths and that the boys stayed away from the encampments because of that. This one had come into the military camp all the same and Hamilton had let him into his billet. His first mistake. Before he took the wallet the little prick stole Capitanes from Gost and one of the other Frenchmen, and the week before that something else went as well, guns or ammunition, the soldiers thought, because there'd been such an uproar around the place. Hamilton was sure that was the Kabyle boy, too. A small dried monkey head belonging to one of the Frenchmen, it turned out to be, that such a fuss was made of.

When he went out to it the next morning the little settlement of Bou Saada seemed to have changed overnight around the bordj. Now he could see a service station and a café under the eucalyptus trees, and, further on, what turned out to be a dry-goods store. Houses beyond that, shacks, and, behind them, little more than a cemetery with its bluish domes and white gravestones.

He moved through the streets, aware of children staring at him and of the dark-robed women looking down and stepping away as they passed him by, this Nazarene. But the men stared as he walked by them, stared hard at him, the desert-faced men squatting against buildings and gazing up at him as he walked past. He tried to look back, but found he could not. Berbers, some of them, their smooth faces heavy with dark blood and, when their rust-coloured buzzard eyes were not turned upon you like this, their sense of complete preoccupation. He would walk to the edge of the cemetery and back, and then he would try again to confront them.

For they were the gateway, he knew that, these Berbers, and would bring him to this boy with the name that meant

angel

, in this land where angels live among you and can be seen as light, where sometimes everything is light, all and only light and seeing. And where, at the same time, there was this, the world he had entered now, where you smelled the perfume of wisteria on one side of the street and on the other side the stink of a dead dog. And where, later, he knew, you could smell the night smell of the desert that lay further to the south, which was always the smell of shit and dust and nothing else. The world that looks back at you without pity, when you try to see it. What could change that, how could that be transformed, redeemed?

This is what I have come to find out, behind the gaze of these desert men and in this Amazigh boy who has taken my mahfaza and yet has led me here to find everything that is not money

â

On the third day of looking, miles from the bordj and towards the bottom of a salty incline whose ridge the mule had brought him to, and suddenly, the man found the boy. He was squatting with his back to him, his cloak over his head and his chalwar pulled down. He was doing his daily business. The glisten of it at his heels, coiling on the dry, lifeless soil of the Hodna.

Hamilton pulled the mule's head away from the brink. He knew it could be anyone, this figure down there, but he also knew that he'd found him at last. How could it have been so easy? He'd just taken possession of him again, of Anir, the angel. What do you do with another being, when you own him like this? What is there to stop you? What is there to be stopped? What is the thing you intend to do, and is it really the thing you are beginning to think of?

He remembered the old saying.

A ripe pomegranate on the ground. Whoever picks you up can have you

.

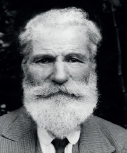

1933â2007

Author, Nobel Prize winner

By G. S. Trott

Raymond Thomas Lawrence was born on 11 October 1933 at Springfield, North Canterbury, to Adam Raymond Lawrence, a farmer, and Beryl née Adams, who taught at the local primary school. A twin brother died at birth; there were no other siblings. He was home-schooled by his mother and at the local primary school till early teenage, after which he experienced five unhappy years at an exclusive boys' school in Christchurch. From 1952 a further, similar and academically fruitless time was spent at the local university college, followed by a period in southern and south-east Asia, Europe, the Middle East and, at greatest length, North Africa, where he took part in the Algerian War of Independence (1954â62) in the wilayat of Rabah Bitat and, later, that of Larbi Ben M'Hidi, both of these men important resistance leaders. Claims that he was in fact in the French Foreign Legion at this time and a part of the brutal repression of the uprising, and claims that he overstated and even entirely invented this period of his life, have been convincingly dismissed.

His first novel

Miss Furie's Treasure Hunt

(1960) was begun in these years and completed in London; it has been described as a perversion of the Hansel and Gretel story cast in domestic terms, and received strong responses, both positive and negative, from readers and literary critics. His second novel,

Frighten Me

(1965), although more nearly conventional, had a similar, if slightly more negative, reception; together with

Flatland

(1966) it follows the growth and maturation of its protagonist, Thomas Hamilton, a recurring and autobiographical figure in Lawrence's

oeuvre

, as he moves to North Africa and becomes involved in a local war of independence there.

After ten years spent travelling and teaching in North Africa and Europe, Lawrence returned to his home country in 1971.

Natural Light

(1973), his first short story collection, alternates stories set locally with others set in North Africa, exploring similarities and contrasts, not without ironic emphasis.

The Outer Circle Transport Service

(1976) is generally agreed to be the work in which he marks his break with Europe and his first commitment to what, in the title of a later novel, he would refer to as the âother-people' of the world. It follows the fortunes of Julia Perdue, an

ingenue

and possibly the most attractive character in Lawrence's writing, in her journey away from Western values and towards an understanding of the lives of the dispossessed. This protagonist returns in

Bisque

(1980), where she moves through a series of adventures on the Mediterranean island of Ibiza that slowly darken as she becomes involved with a former Nazi sympathiser and Franco supporter.

The Long Run

(1982), his second volume of stories, was well received, as was the satire

Nineteen Forty-Eight

(1984), which renders Orwell's dystopia in everyday and localised terms while still using and developing his characters; this novel is widely acknowledged to be an outlier, however, in what seems now to be the inevitable progression of his

oeuvre

.

Starting with

Bisque

, Lawrence's next three novels are now widely acknowledged as the core of his achievement and the basis of his Nobel award.

Kerr

(1988), acknowledged as his masterwork, takes its eponymous protagonist on a raft journey inspired by the author's own solo raft trip from North Africa to Ibiza in 1962. Its visionary conclusion and the question whether its protagonist has indeed survived the voyage are still debated by scholars.

The Long Run

(1992) reintroduces the figure of the youth Anir from

Flatland

, in what has been seen as an unexpected return to the Algeria of Lawrence's earlier fiction, a country now transformed into a universal theatre of conflict and suffering without a necessarily specific geography. These themes were continued in

Other-people

(1996), whose Christian connotations and the links made in it between its protagonist and the historical figure of Christ have been widely noted; its extremely provocative final scenes continue to prove contentious and the novel continues to be Lawrence's most-debated work of fiction.

Following the announcement of his Parkinson's disease, in 1996, some argued for a slight decline in the quality of Lawrence's work.

Mastering

(1994) and

Mistresses

(1999) are short story collections mingling earlier and later interests; the slight unevenness of these was remarked on by some critics, though others saw both volumes as demonstrating the stylistic and thematic development of his

oeuvre

over many years.

Constanze

(2001), the last of his work published in his lifetime, revives the character of Julia Perdue as an older woman reminiscing about her life and has been seen as having strong autobiographical undertones; critics have remarked on the sexual ambiguity of his protagonist and the re-emergence of cross-dressing themes from the earlier âJulia novels' as well as some of his other earlier and middle-period fiction.

In 1976

The Outer Circle Transport Service

was awarded the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and the National Book Award. In 1981

Bisque

won the National Book Award and was regionally shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writer's Prize. In 1989

Kerr

, too, won the National Book Award and was regionally shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers' Prize, and for the Booker McConnell Prize in that year.

Constanze

was longlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2002. In 1995 Raymond Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, for (in the words of his Citation) âthe spontaneity and integrity with which [he] has shown what happens to the European mind far from home, and for his holding before our collective gaze the wretched of the earth'. His development and popularisation of anti-realist modes were also mentioned. In 1996 Raymond Lawrence was awarded the Order of Merit.

The Raymond Lawrence Trust has published two of the writer's posthumous works.

Understanding the Cardinal

(2009) collected further stories from earlier in Lawrence's life, including what is now seen as his juvenilia, while

The Back of His Head

(2015) is noted for a distinctive change in the tone of Lawrence's writing and for raising questions as to its authorship. Questions about the quality of these works and the appropriateness of their publication have been convincingly dismissed. Further posthumous publication is planned.

Raymond Lawrence died in controversial circumstances on 14 June 2007, in an explosion on the city campus of the University of Canterbury which destroyed a number of buildings, including the creative writing school that had been named for him; seven young people also died in this disaster. This event was thought for some time to have been the work of agents from his Algerian period or elsewhere in the Middle East bent on assassination or by agents of the

Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure

(DGSE). A subsequent coronial enquiry identified its cause, however, as a fault in a gas supply. Cultic reports of Lawrence's reappearance after this date have been convincingly dismissed.

Raymond Lawrence remained unmarried throughout his life and had no issue, though he adopted his nephew and literary executor Peter Or as his son in 1992. He was involved in a number of significant relationships, with the painter Phyllis Button, the novelist Marjorie Swindells and others. The nature of his long relationship, revealed in

Constanze

and elsewhere, with the artist and poet Driss Dris Batuta (1940â1990), whom he first met in 1953 and to whom he returned regularly in Tangier, Morocco, is not known. His home on the Kashmir Hills in Christchurch was for forty years the focus of a group of writers, artists and intellectuals known for their exclusiveness. Maintained by the Raymond Lawrence Trust, the Raymond Lawrence Residence is open to the public daily from 10:00 a.m. in summer and 1:00 p.m. in winter. An admission fee is charged.

Suggestions and sources:

Trott, G.

Raymond Lawrence: Years of Lightning

. Bumpkin Press, 1983?

Trott, G.

The Raymond Lawrence Story

. Hazard Press, 2015.