The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (24 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

As was his custom by now, Michael Jackson stood at the vanguard. He wrote for the

Washington Post

in November 1983 what was very likely the first article in a mainstream American newspaper about pairing beer with food, and vice versa. The

Post

was still in its Watergate afterglow of nine years before, the third-largest daily US newspaper by circulation, read not only by the denizens of the White House and Congress but also by a wide regional audience

from central Virginia through Maryland. On November 16, 1983, the week before Thanksgiving, they awoke to a discursive, at times humorous, essay meandering through four pages on which beers to have with which foods on the big feast day. Jackson eased his readers into the unfamiliar territory with wine as well as with an emphasis on the geographic origins of different beers, which in itself might have seemed unfamiliar. For the main course:

With the centerpiece of the meal, the turkey, the wine-drinker has a difficult choice. Should it be a medium-dry white? Or a drier medium-bodied red? Among beers, I would opt for a pale but medium-dry brew of the type produced in the city of Munich and elsewhere in Bavariaâ¦. With just a hint of sweetness to match some of the turkey's accompaniments, these Munich Light beers have plenty of body without being too filling. Their alcohol content is pretty ordinary, at well under 4.0 percent by weight or 5.0 by volume. As for serving temperatures, the simplest rule to observe is that any beer from Munich or elsewhere in Bavaria should be served chilled but not to American popsicle level; not less than 48 degrees, in fact.

It was something any person with healthy taste buds could get right away: certain beers went well with certain foods. But it was a matter of getting consumers to pair the beers with the foods in the first place. The era of light beerânot to be confused with the “Light” that Jackson referred to, which had to do with the German beers' colorâwas in full force, with tens of millions being spent on television and print ad campaigns to move tens of millions of barrels. Anheuser-Busch had debuted Bud Light (formerly Budweiser Light) in 1982, with a commercial of a mighty Clydesdale running through a seemingly endless pasture, a deep, unseen voice intoning, “A light beer worthy of the King of Beers.” Miller Lite, the brand it was meant to usurp, inaugurated the celebrity-studded Lite Beer Bowling Tournament in September of the same year. Beer was still seen as a beverage to be consumed when you're having six, with or without dinner, and as close to “popsicle” as possible. As for its geographic origins, it was not important if it wasn't local. Attempts to integrate American beer with gourmet food seemed as hopeless as Rodney Dangerfield's attempts to roll a strike in the Lite Beer Bowling Tournament (he couldn't down a pin).

The sit-down beer-food tastings and Jackson's articles were a start, though. He would write more for the

Post

and other American publications throughout the decade and would host pairings at venues that included the swanky Pierre hotel in Midtown Manhattan, where four Belgian chefs devised the lunch

menu; Monk's Cafe in Philadelphia's Center City as well as at the metropolis's Museum of Archeology and Anthropology; and the Century House in the hamlet of Latham, New York. That one, on November 4, 1986, even got a little advance press.

English beer authority Michael Jackson will visit Albany Nov. 4 to conduct “The Quintessential Beer Tasting,” at 8 P

M

at the Century House in Latham. The international beer tasting, sponsored by Albany's Newman Brewing Company, will be open to the publicâ¦. For the Albany show, he will lead a guided tour through a selection of 13 international beers. Tickets at $6 per person are available through Newman's Brewery ⦠and at the door.

Largely, though, press for the tastings or for craft beer generally was slim to none. From consumer media, it was mostly of the parachute variety: The reporter would be assigned to cover an event like the Great American Beer Festival; he would arrive, gather what background he could, garner some quotes from attendees and organizers for color, and be gone as quickly as he arrived. Rare, too, was the byline with any gravitas in the industry or with readers. Frank J. Prial's spring 1979 visit to Jack McAuliffe's New Albion was so far the most storied exampleâthe

Times

's wine critic stomping about the wilds of Sonoma, scribbling notes on craft beer! When T. R. Reid of the

Washington Post

phoned Daniel Bradford to tell him he was coming to Boulder for the second GABF in June 1983, it was all Bradford could do to not shout across the office to his boss, “Charlie, the

Washington Post

called, and they're sending a guy to cover this!” The silver lining in consumer coverage was that it had long ceased writing of craft beer as if it were a blip in the marketplace or a mere curiosity; knowledge about the brands and the brewing process was diffuse enough, and sources plentiful enough, that these parachuted reporters could get up to speed quickly.

From trade media, the coverage was more in-depth, and followed the conversational, we're-all-in-this-together tone set by homebrewing club newsletters like those of the Maltose Falcons in Los Angeles or self-published memoranda like Fred Eckhardt's

Amateur Brewer

out of Portland or Charlie Papazian's increasingly professionalized

Zymurgy,

the quarterly out of Boulder. As we've seen, they all mixed recipes and reviews with whatever news, including information on upcoming events, that could be amassed in the pre-Internet age, when even a long-distance phone call could be an event. Wider industry trade publications covered craft beer as well. The three most prominent were

the monthly magazine

Brewers Digest,

the multifaceted

Modern Brewery Age,

and the bimonthly magazine

All About Beer,

started by Mike Bosak in 1979 with a sixteen-page issue that included news of homebrewing's federal legalization and Anchor's production at its new Mariposa Street location. The latter publication, which might have been the largest with a claimed readership of 160,000 by 1983, was dismissed by many in the industry, as it sometimes sold editorial space (including the cover).

It was Fred Eckhardt, though, even more than Jackson, who dragged craft beer coverage over the hump from esoteric toward commonplace. On April 25, 1984, a Friday, tucked onto a page of Portland's daily newspaper, the

Oregonian,

with ads for Diet 7-Up and Atta Boy dog food as well as a call for contestants for a rice-cooking competition, were two brief stories and one photograph, what those in the newspaper trade call a thumbnail. The shorter of the two articles was headlined B

EER EXPERT WRITES COLUMN,

and it gave Eckhardt's CV in digestable nuggets: “Eckhardt is a âself-taught' amateur brewer who started making his own beer in 1969 [sic], in the fashion his father did during Prohibition.” It was the warm-up for the longer article: M

OST AMERICAN BEERS LACK ONE THING: TASTE.

The ensuing column marked the opening of what would be the first regular American newspaper coverage of craft beer. The type of writing championed by Michael Jackson out of England had found a domestic expression in Eckhardt in the

Oregonian,

which was one of the most respected midsize dailies in the country, with a weekday circulation of 249,000. And the ex-Marine did not hold back.

From that first column on April 25: “When drinking San Francisco Steam Beer [Anchor Steam], or a well-made dark beer, you notice the taste. Most domestic brews taste alike and many of us are forced to look to imports for the kinds of taste we used to find in American beer.” The list of “Twenty Beers with Class” at the end of the column included Anchor Liberty Ale and Sierra Nevada Pale Ale.

*

From a June 20 column after Eckhardt returned from the third GABF: “Since the voting was limited, and somewhat chauvinistic as a popularity contest, I am taking the liberty to list my choices for the twenty top beers at the festival. And, yes, I did taste all of the thirty-six beers which are not available in these partsâ¦. Rumor mills say the New Amsterdam Amber (already in California) will come north this fall.”

And this one on the Fourth of July of the same year:

Anyone who thinks that great beer has to be brought into Portland from a great distance just hasn't been paying attention. Some of the best beer in the world is made within 200 miles of Portland, where there are six breweriesâ¦. Good beer is becoming stylish, and if we hang in there, there'll be real taste in American beer again. In fact, it is here now. We have Redhook and Grants [sic] brewing world-class beer, but only on draft. The new Ponzi operation, Columbia River Brewing [later BridgePort], is set to produce beer by mid-August, but also only on draft.

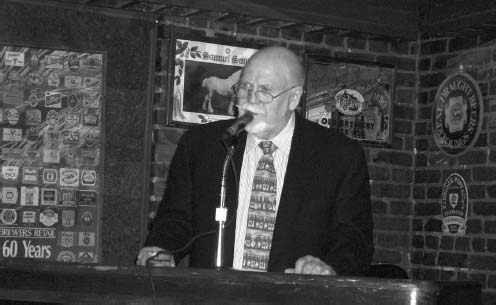

Fred Eckhardt speaking at the old Brickskeller beer bar in Washington, DC, in 2002.

COURTESY OF DAVE ALEXANDER

Eckhardt's

Oregonian

columns continued through the 1980s and set a precedent in mainstream outlets not only for opinionated, conversational coverage of craft beer but also for sometimes putting the cart before the horse when it came to writing about brewers and their beers. Eckhardt, for one, would sometimes suggest a particular style to one of the Portland breweriesâa winter ale, sayâand then write about it once it was produced. Or he would write about a style that was unavailable from local brewers as a none-too-subtle nudge. Like Jackson's coverage, Eckhardt's combined a genuine desire to educate the consumer with a soft spot for mentoring these start-up breweries.

William Least Heat-Moon also had ulterior motives. He wanted something to write about that might require a road trip. Ex-Navy, with a PhD in English from the University of Missouri, he had crafted a bestselling memoir in the

early 1980s called

Blue Highways,

about traveling America's back roads after he lost his job and his estranged wife on the same winter's day. Critics compared it favorably to John Steinbeck's

Travels with Charley

and Jack Kerouac's

On the Road.

The pursuit of rediscovering something in Americaânamely areas empty of strip malls and fast-food joints, and the characters who inhabited themâperhaps uniquely qualified Heat-Moon to write the first long-form consumer magazine story about beer since the craft movement began. Besides, the third paragraph of

Blue Highways

could all but serve as a credo for the movement's entrepreneurs: “A man who couldn't make things go right could at least go. He could quit trying to get out of the way of life. Chuck routine. Live the real jeopardy of circumstance. It was a question of dignity.”

Heat-Moon's 6,978-word chronicle of his visits to nearly every brewpub and craft brewery in the country in the mid-1980sâKen Grossman's Sierra Nevada was the big exception, owing to time and traveling expensesâwas published by the 130-year-old

Atlantic Monthly

in November 1987 under the entirely appropriate headline A

GLASS OF HANDMADE.

Heat-Moon and a friend, whom he called The Venerable Tashmoo,

*

not only sampled myriad glassfuls but also learned the brewers' back stories and techniques, starting in Albany.

One September afternoon The Venerable and I watched Bill Newman work; we gnawed grains of his various malted barleys; we helped him stir the mash; we tasted the sweet wort, the hopped wort, the green beer, and the finished ale fresh from the maturing tank. Young Newman (to be a micro-brewer is to be under forty) wanted to give his city a choice of flavors, to fill a cranny that the industrial breweries left as they bought up regional companies.

The underlying theme of the story was one of the underlying themes of the craft beer movement: local variety versus mass production that had engineered out the former and eschewed the latter. With this came the challenges, and Heat-Moon recorded those, too. It was a daily grind with distributors, retailers, and especially consumers, even in 1987âtwenty-two years after Fritz Maytag walked into the old Anchor on Eighth Street, eleven years after Jack McAuliffe started building his gravity system in the grape warehouse, and five years after Charlie Papazian and Daniel Bradford launched the Great American Beer Festival.

I told the bartender what I'd seen at lunch in a cafe downtown: a manâfifties, blue blazer, penny loafers,

USA Today

under his armâordered a Hale's Pale American Ale, took a single sip, and handed it back to the bartender, who dumped it and then passed across a bottle of Heineken. The bartender said, “I don't see many conversions of middle-aged people. The beer a man's drinking when he's thirty is the one he tends to believe in the rest of his life.”