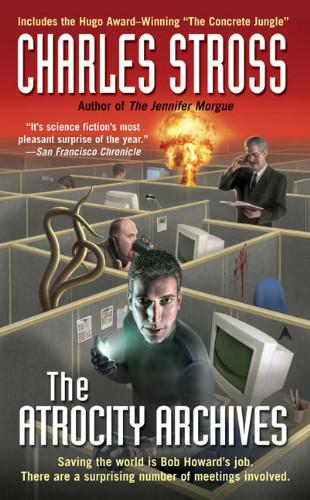

The Atrocity Archives

eVersion 2.0 - click for scan notes

Charles Stross

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors write, but not in a vacuum. Firstly, I

owe a debt of gratitude to the usual suspects—members of my local

writers workshop all—who suffered through first-draft reading hell and

pointed out numerous headaches that needed fixing. Paul Fraser of

Spectrum

SF

applied far more editorial muscle than I had any right to

expect, in preparation for the original magazine serialization;

likewise Marty Halpern of Golden Gryphon Press, who made this longer

edition possible. Finally, I stand on the shoulders of giants. Three

authors in particular made it possible for me to imagine this book and

I salute you, H. P. Lovecraft, Neal Stephenson, and Len Deighton.

"The Atrocity Archive" is a

science fiction novel. Its form is that of a horror thriller

with lots of laughs, some of them uneasy. Its basic premise is that

mathematics can be magic. Its lesser premise is that

if

the

world contains things that (as Pratchett puts it somewhere) even the

dark is afraid of,

then

you can bet that there'll be a secret

government agency covering them up for our own good. That last phrase

isn't ironic; if people suspected for a moment that the only thing

Lovecraft got wrong was to underestimate the power and malignity of

cosmic evil, life would become unbearable. If the secret got out and

(consequently) other things got in, life would become impossible.

Whatever then walked the Earth would not be life, let alone human. The

horror of this prospect is, in the story, linked to the horrors of real

history. As in any good horror story, there are moments when you cannot

believe that anyone would dare put on paper the words you are reading.

Not, in this case, because the words are gory, but because the history

is all too real. To summarise would spoil, and might make the writing

appear to make light of the worst of human

accomplishments. It does not. Read it and see.

Charlie has written wisely and well in the

Afterword about the uncanny parallels between the Cold War thriller and

the horror story. (Think, for a moment, what the following phrase would

call to mind if you'd never heard it before: "Secret intelligence.")

There is, however, a third side to the story. Imagine a world where

speaking or writing words can literally and directly make things

happen, where getting one of those words wrong can wreak unbelievable

havoc, but where with the right spell you can summon immensely powerful

agencies to work your will. Imagine further that this world is

administered: there is an extensive division of labour, among the

magicians themselves and between the magicians and those who coordinate

their activity. It's bureaucratic, and also (therefore) chaotic, and

it's full of people at desks muttering curses and writing invocations,

all beavering away at a small part of the big picture. The

coordinators, because they don't understand what's going on, are easy

prey for smooth-talking preachers of bizarre cults that demand

arbitrary sacrifices and vanish with large amounts of money. Welcome to

the IT department.

It is Charlie's experience in working in and

writing about the Information Technology industry that gives him the

necessary hands-on insight into the workings of the Laundry. For

programming is a job where Lovecraft meets tradecraft, all the time.

The analyst or programmer has to examine documents with an eye at once

skeptical and alert, snatching and collating tiny fragments of truth

along the way. His or her sources of information all have their own

agendas, overtly or covertly pursued. He or she has handlers and

superiors, many of whom don't know what really goes on at the sharp

end. And the IT worker has to know in their bones that if they make a

mistake, things can go horribly wrong. Tension and cynicism are

constant companions, along with camaraderie and competitiveness. It's a

lot like being a spy, or necromancer. You don't

get out much, and when you do it's usually at night.

Charlie gets out and about a lot, often in

daylight. He has no demons. Like most people who write about eldritch

horrors, he has a cheerful disposition. Whatever years he has spent in

the cellars haven't dimmed his enthusiasm, his empathy, or his ability

to talk and write with a speed, range of reference, and facility that

makes you want to buy the bastard a pint just to keep him quiet and

slow him down in the morning, before he gets too far ahead. I know:

I've tried. It doesn't work.

I first encountered Charles Stross when I worked

in IT myself. It was 1996 or thereabouts, when you more or less had to

work in IT to have heard about the Internet. (Yes, there was a time not

long ago when news about the existence of the Internet spread

by

word of mouth

.) It dawned on me that the guy who was writing

sensible-but-radical posts to various newsgroups I hung out in was the

same Charles Stross who'd written two or three short stories I'd

enjoyed in the British SF magazine

Interzone

: "Yellow Snow,"

"Ship of Fools," and "Dechlorinating the Moderator" (all now

available

in his collection

TOAST

, Cosmos Books, 2002).

"Dechlorinating the Moderator" is a science

fiction story about a convention that has all the trappings of a

science fiction convention, but is (because this is the future) a

science

fact

convention, of desktop and basement high-energy

fundamental physics geeks and geekettes. Apart from its intrinsic fun,

the story conveys the peculiar melancholy of looking back on a con and

realising that no matter how much of a good time you had, there was

even more that you missed. (All right: as subtle shadings of emotion go

this one is a bit low on universality, but it was becoming familiar to

me, having just started going to cons.) "Ship of Fools" was about the

Y2K problem (which as we all know turned out not to be a problem, but

BEGIN_RANT that was entirely thanks to programmers who did their jobs

properly in the first place back when only geeks and astronomers

believed the twenty-first century would

actually arrive END_RANT) and it was also full of the funniest and most

authentic-sounding insider yarns about IT I'd ever read. This Stross

guy sounded like someone I wanted to meet, maybe at a con. It turned

out he lived in Edinburgh. We were practically neighbours. I think I

emailed him, and before too long he materialised out of cyberspace and

we had a beer and began an intermittent conversation that hasn't

stopped.

He had this great idea for a novel: "It's a

techno-thriller! The premise is that Turing cracked the NP-Completeness

theorem back in the forties! The whole Cold War was really about

preventing the Singularity! The ICBMs were there in case godlike AIs

ran amok!" (He doesn't really talk like this. But that's how I

remember

it.) He had it all in his head. Lots of people do, but he (and here's a

tip for aspiring authors out there) actually wrote it. That one,

Burn

Time,

the first of his novels I read, remains unpublished—great

concept, shaky execution—but the raw talent was there and so was the

energy and application and the astonishing range of reference. Since

then he has written a lot more novels and short stories. The short

stories kept getting better and kept getting published. He had another

great idea: "A family saga about living through the Singularity! From

the point of view of the cat!" That mutated into the astonishing

series

that began with "Lobsters," published in

Asimov's SF

, June

2001. That story was short-listed for three major SF awards: the Hugo,

the Nebula, and the Sturgeon. Another, "Router," was short-listed for

the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Award. The fourth,

"Halo," has been short-listed for the Hugo.

Looking back over some of these short stories,

what strikes me is the emergence of what might be called the Stross

sentence. Every writer who contributes to, or defines, a stage in the

development of SF has sentences that only they could write, or at least

only they could write

first

. Heinlein's dilating door opened up

a new way to bypass explication by showing what is taken for granted;

Zelazny's dune buggies beneath the racing moons

of Mars introduced an abrupt gear-change in the degrees of freedom

allowed in handling the classic material; Gibson's television sky and

Ono-Sendai decks displayed the mapping of virtual onto real spaces that

has become the default metaphor of much of our daily lives. The

signature Stross sentence (and you'll come to recognise them as you

read) represents just such an upward jump in compression and

comprehension, and one that we need to make sense not only of the

stories, but of the world we inhabit: a world sentenced to Singularity.

The novels kept getting better too, but not

getting published, until quite recently and quite suddenly three or

four got accepted more or less at once. The only effect this has had on

Charlie is that he has written another two or three while these were in

press. He just keeps getting faster and better, like computers. But the

first of his novels to be published is this one, and it's very good.

We'll be hearing, and reading, a lot more from

him.

Read this now.

Ken MacLeod

West Lothian, UK

May 2003

1. ACTIVE SERVICE

Green sky at night; hacker's delight.

I'm lurking in the shrubbery behind an

industrial unit, armed with a clipboard, a pager, and a pair of bulbous

night-vision goggles that drench the scenery in ghastly emerald tones.

The bloody things make me look like a train-spotter with a gas-mask

fetish, and wearing them is giving me a headache. It's humid and

drizzling slightly, the kind of penetrating dampness that cuts right

through waterproofs and gloves. I've been waiting out here in the

bushes for three hours so far, waiting for the last workaholic to turn

the lights out and go home so that I can climb in through a rear

window. Why the hell did I ever say "yes" to Andy? State-sanctioned

burglary is a lot less romantic than it sounds—especially on standard

time-and-a-half pay.

(You bastard, Andy. "About that application for

active service you filed last year. As it happens, we've got a little

job on tonight and we're short-staffed; could you lend a hand?")

I stamp my feet and blow on my hands. There's no

sign of life in the squat concrete-and-glass block in front of me. It's

eleven at night and there are still lights burning in the cubicle hive:

Don't these people have a bed to go home

to? I push my goggles up and everything goes dark, except the glow from

those bloody windows, like fireflies nesting in the empty eye sockets

of a skull.

There's a sudden sensation like a swarm of bees

throbbing around my bladder. I swear quietly and hike up my waterproof

to get at the pager. It's not backlit, so I have to risk a precious

flash of torchlight to read it. The text message says,

MGR LVNG

5

MINS.

I don't ask how they know that, I'm just grateful that there's only

five more minutes of standing here among the waterlogged trees, trying

not to stamp my feet too loudly, wondering what I'm going to say if the

local snouts come calling. Five more minutes of hiding round the back

of the QA department of Memetix (UK) Ltd.—subsidiary of a

multinational

based in Menlo Park, California—then I can do the job and go home.

Five

more minutes spent hiding in the bushes down on an industrial estate

where the white heat of technology keeps the lights burning far into

the night, in a place where the nameless horrors don't suck your brains

out and throw you to the Human Resources department—unless you show a

deficit in the third quarter, or forget to make a blood sacrifice

before the altar of Total Quality Management.

Somewhere in that building the last late-working

executive is yawning and reaching for the door remote of his BMW. The

cleaners have all gone home; the big servers hum blandly in their

air-conditioned womb, nestled close to the service core of the office

block. All I have to do is avoid the security guard and I'm home free.

A distant motor coughs into life, revs, and

pulls out of the landscaped car park in a squeal of wet tires. As it

fades into the night my pager vibrates again:

GO

GO GO

. I edge forward.

No motion-triggered security lights flash on.

There are no Rottweiler attack dogs, no guards in coal-scuttle helmets:

this ain't that kind of movie, and I'm no Arnold Schwarzenegger. (Andy

told me: "If anyone challenges you, smile, stand up

straight, and show them your warrant card—then phone me. I'll handle

it. Getting the old man out of bed to answer a clean-up call will earn

you a black mark, but a black mark's better than a cracked skull. Just

try to remember that Croxley Industrial Estate isn't Novaya Zemlya, and

getting your head kicked in isn't going to save the world from the

forces of evil.")