The Atlantic and Its Enemies (46 page)

Nixon had to wrestle endlessly with the external problems, including of course that of the dollar’s world role, and he neglected the internal problems - finding Congress difficult to deal with, and anyway lacking powers to deal with it head-on. The Constitution itself in effect left the State sometimes paralysed: it was weaker in many ways even than the Swiss central state (where on occasion the cabinet had nothing to do but play cards). By contrast, the legal machinery was much more developed: there were 312 lawyers per 100,000 people, as against 190 in Germany and 134 in England. Given that the President could be frustrated by Congress and/or the Supreme Court, if they so decided, the very system of government was not well-equipped to deal with a general crisis, and in 1973 much went wrong.

With Nixon’s resignation, the United States went into a sort of tailspin. The inflation - or rather ‘stagflation’ - went together with a, for the USA, very strange phenomenon, that much of business now appeared to fail: some of the greatest names in American business got into trouble, symbolized by the fall of one of the largest modernizing enterprises of all, the Penn Central railway. Chrysler itself was saved by the Republicans only as a national symbol: by 1980 the collapse of public services was such that 88 per cent of Americans went to work by automobile. ‘The pursuit of happiness’, in the foundation charter of the United States, has always struck foreigners as funny. That is a misunderstanding of the original, which was just a polite way of saying ‘money’ (‘commodity’ is a similar euphemism, and in English ‘honorarium’, ‘remuneration’,

etc.

have the same function). As the seventies went on, the expression could only be used with irony. Much of the country - in its way, the real part - was still innocent and old-fashioned: churches got a billion dollars for building, twice what public hospitals got, and the modern ills of family breakdown and drug addiction passed these parts by. But overall the country was paying for the very obverse of the pursuit of happiness, and there was a sort of civil war. It was an extremely strange period. Hollywood became anti-patriotic, and embarked upon a campaign of anti-American film-making, with Robert Redford in the lead, though he had several less talented imitators. But there was hysteria at large. Senators George McGovern and Ed Muskie referred to Nixon in apocalyptic terms: ‘one-man rule’, ‘this tyrant’. The ‘Pentagon Papers’ affair, in 1971, which had then led to Watergate, was a disaster for the whole concept of national security, encouraging babyish attention-seeking among journalists without the talent of the pioneers in the business; and a campaign was launched against the old CIA, its assorted enemies being cast as martyrs (e.g. Seymour Hersh’s work on the Chilean coup in

The New York Times

in 1974). Various radicals were acquitted, and there were the usual conspiracy theories as to the Kennedy assassination, even a House committee accepting primitive legendry as to how the Mafia had caused it. Tom Wolfe wrote a superb little essay, ‘Radical Chic’, on the attitudinizing of New York money at social events staged on behalf of grotesque killers.

Politics fell into paralysis, and foreign policy for a time became mouthings. Congress was now cutting the powers of the presidency. In November 1973, even before he fell, Nixon had faced a Resolution preventing him from sending troops overseas for any length of time if Congress did not formally give support, and the Jackson-Vanik amendment of 1973-4 put an obstacle in the way of his policies towards the Soviet Union, by cancelling favourable trade arrangements if Moscow did not cease harassing Jewish would-be emigrants. In July-August 1974 Congress again paralysed US handling of another strategic headache, on Cyprus, where first Greeks and then Turks had intervened. Both were in NATO, and each had treaty rights to invoke; Cyprus mattered because there were British bases there, and the island was on the very edge of the Middle East. One set of Greeks attacked another set of Greeks, and there was a Turkish minority with paper rights, which the Turkish army then invoked, occupying a third of the island. The enraged Greek lobby intervened, against the advice of Kissinger, who felt that it was giving up the chance of a long-term solution in order to vent short-term steam, a judgement proven correct. That autumn Congress restricted the CIA, and in 1975 frustrated any positive policy towards Angola, where a civil war killed off a fifth of the population. Endless new committees in both Houses now supervised aspects of foreign affairs, and the old congressional committees which had been notorious for insider dealings, with long-term chairmen who knew which levers to pull, were replaced by an allegedly open system in which nothing worked at all. The staff monitoring the White House rose to 3,000.

The seventies were a period when the formula of fifties America appeared to be failing, and there was a symbol of this. The very capital of capitalism was in trouble. New York was reigned over by a Mayor John Lindsay, a man in the Kennedy mould, who shrank from making enemies. The city’s workers were collecting wages that, with inflation, bought less and less; in 1968 the rubbish was not collected for a week, and rats ran through the streets of Manhattan. The sewage workers then struck, and from Harlem hundreds of thousands of gallons of raw sewage floated along the river. This (1971) was the background to the famous riot, in which ‘hard hats’ working on building sites near Wall Street and the World Trade Center attacked anti-war protestors demonstrating there. The protestors fled, to fight (successfully) another day. Lindsay had attitudinized in their direction, decreeing that the city administration’s flag should, in mourning, be put at half-mast. He was forced to restore it to celebration mode, but then found another and much more damaging way to deal with the situation. He made bargains with the unions. In the USA these often had some association with organized crime, and might turn into protection rackets. The transport workers got an 18 per cent salary increase, an extra week of vacation, and fully paid pensions; the district councils, bureaucrats, had higher wages and were allowed retirement after twenty years; the teachers received increases of 22-37 per cent. Lindsay made New York the capital of crime. In the 1960s it had 7.6 murders per 100,000 people and from 1971 to 1975 21.7.

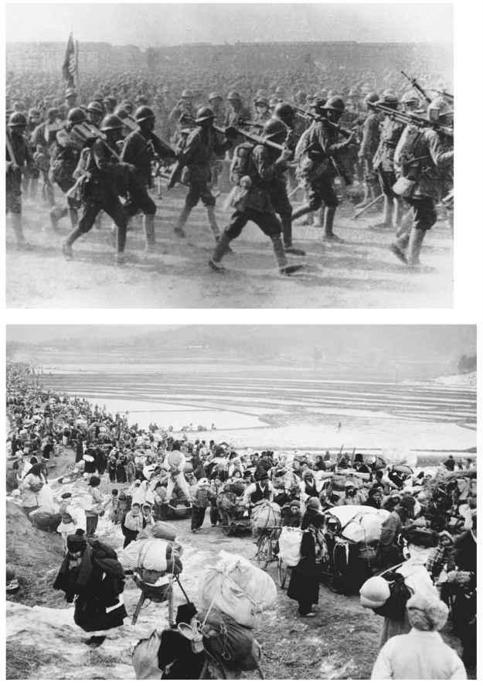

1. and 2.

Old business.

The former Chief of the High Command, Wilhelm Keitel, fails to persuade the Nuremberg judges not to hang him, while a delighted former finance minister, Hjalmar Schacht, signs autographs after his acquittal, September and October 1946

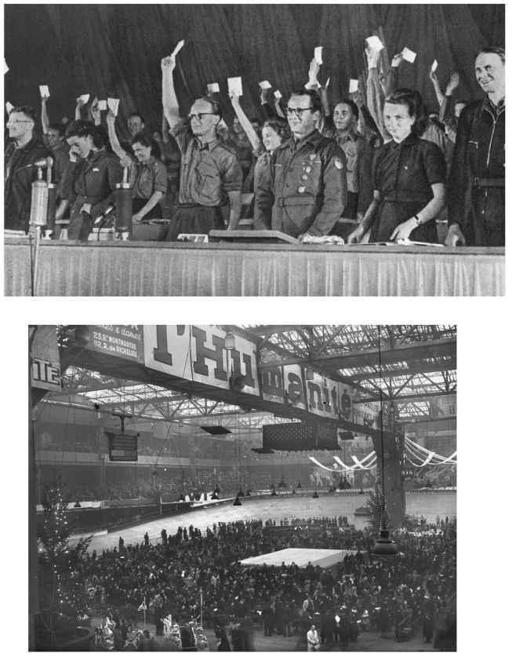

3. and 4.

Germany in 1946.

Berliners collecting firewood in the Berlin Tiergarten, and a tram filling with passengers in Dresden

5. and 6.

The chilly Communist future.

The young Erich Honecker being voted first chairman of the Free German Youth; a post-Christmas meeting of the French Communist Party at the Vel d’Hiv, Paris, complete with gloomy Christmas tree, both January 1946

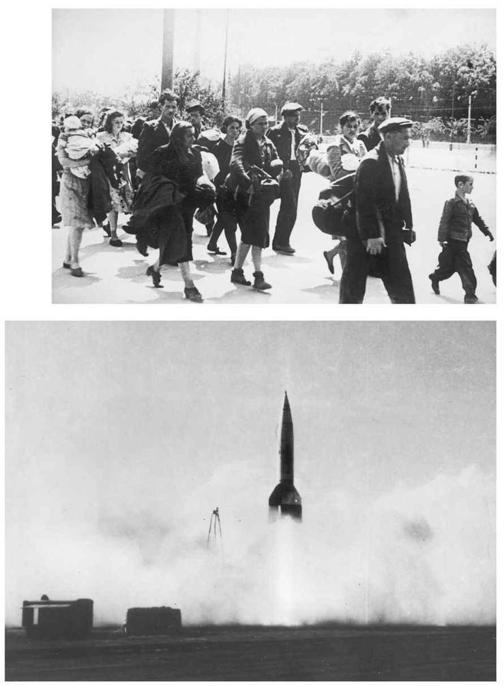

7. and 8.

Aftershocks.

Surviving Jewish families fleeing from Poland in the summer of 1946 following anti-Semitic violence; the origins of the American space programme: a V2 rocket being fired in New Mexico, August 1946

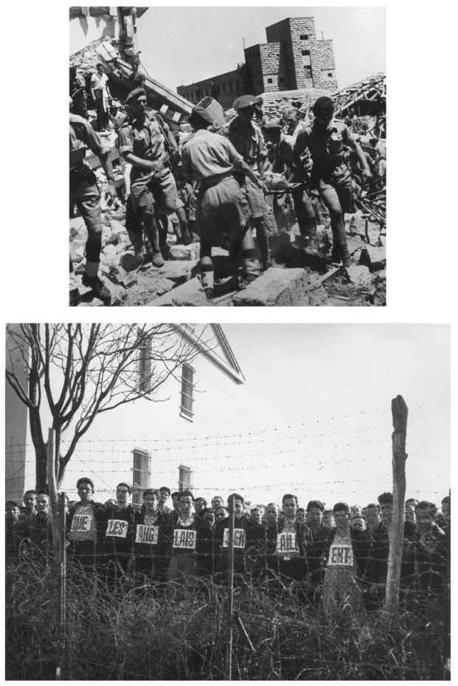

9. and 10.

The end of the British Empire.

British troops pulling casualties from the rubble of their headquarters at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem, July 1946, and Greek Communist prisoners in Salonica with ‘The British Must Go’ spelled out in French on their shirts, March 1947

11. and 12. and 13.

The Cold War coalesces.

George C. Marshall with Vyacheslav Molotov, March 1947; Jan Masaryk and Edvard Beneš in Hradčany Castle, March 1947; Mátyás Rákosi at his desk

14. and 15.

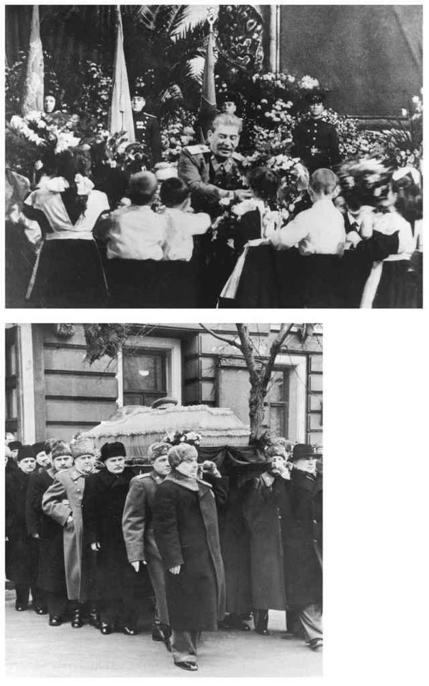

Stalin.

Stalin celebrates his seventieth birthday at the Bolshoi Theatre, January 1950; from right to left: Beria, Malenkov, Vassily Stalin, Molotov, Bulganin and Kaganovich carrying Stalin’s coffin, March 1953