The Assassins of Isis (32 page)

Read The Assassins of Isis Online

Authors: P. C. Doherty

âWho is often represented by a frog,' Amerotke said, scrambling to his feet. He recalled the derelict temple, the circular sanctuary with its grey-paved stone. âOf course,' he breathed, âthe sanctuary was built in the shape of a potter's wheel; that's what Menna meant, whilst the reference to frogs was a joke.'

Â

Â

The late-afternoon breeze was cooling the river as the imperial war barge,

the Vengeance of Isis

, stood off the small causeway leading to the island where the ruins of the Temple of Khnum sprawled under the light of the setting sun. The war barge had been there some time, its blue and gold sail furled, whilst the royal cabin, with its red and silver canopy, stood empty, its side doors open to catch the breeze. Those soldiers and marines not sitting in whatever shade they could find clustered with Amerotke and Shufoy along the taffrail, in the prow or the stern. They shaded their eyes and stared across at that lonely island fringed with its reed and papyrus groves. Even now, despite the presence of the barge and its escort craft, it was a lonely place, the haunt of the hippopotamus, the crocodile and the brilliantly feathered marsh birds whirring up in clamour at this unexpected intrusion. Barges of marines, armed with flaring pitch torches, patrolled the banks, driving off the river beasts from this place now sanctified by the presence of their Pharaoh.

the Vengeance of Isis

, stood off the small causeway leading to the island where the ruins of the Temple of Khnum sprawled under the light of the setting sun. The war barge had been there some time, its blue and gold sail furled, whilst the royal cabin, with its red and silver canopy, stood empty, its side doors open to catch the breeze. Those soldiers and marines not sitting in whatever shade they could find clustered with Amerotke and Shufoy along the taffrail, in the prow or the stern. They shaded their eyes and stared across at that lonely island fringed with its reed and papyrus groves. Even now, despite the presence of the barge and its escort craft, it was a lonely place, the haunt of the hippopotamus, the crocodile and the brilliantly feathered marsh birds whirring up in clamour at this unexpected intrusion. Barges of marines, armed with flaring pitch torches, patrolled the banks, driving off the river beasts from this place now sanctified by the presence of their Pharaoh.

Amerotke himself had reported his findings to the palace. Hatusu and Senenmut had wasted no time. The golden-prowed war barge was immediately readied and, with an escort of lesser craft, began the short journey along the river. Heralds with conches and horns wailing warned all other boats to pull aside as the great oared barge displaying the imperial Horus banner swept up to the island of Khnum. Once it arrived, only Hatusu, Senenmut and the hawk-masked Silent Ones went ashore. Amerotke could only wait and hope. The royal party had been ashore for at least two hours. He glimpsed the occasional movement, the glint of sunlight on weapons, whilst the sound of digging echoed faintly across the water. A sharp-eyed look-out pointed to a plume of smoke, a dark drifting smudge rising up above the trees against the blue sky. A short while later Amerotke glimpsed the imperial canopy sheltering Hatusu from the sun moving through the palm grove down

towards the waterside. A war horn wailed from the island, and immediately the barge readied itself in a patter of running feet and shouted orders from the helmsman and captain. The vessel, scores of oars rising and falling in unison, moved closer to the shore under the guidance of the pilot, the gangplank was lowered and Hatusu, escorted by Senenmut, swept aboard, going directly to the gorgeously caparisoned cabin. Amerotke was ordered to join them, and Hatusu, smiling and joking like a girl at her first banquet, patted the cushions beside her and thrust a goblet of iced fruit juice into his hand. She leaned closer, her perfumed face laced with sweat, eyes bright with life.

towards the waterside. A war horn wailed from the island, and immediately the barge readied itself in a patter of running feet and shouted orders from the helmsman and captain. The vessel, scores of oars rising and falling in unison, moved closer to the shore under the guidance of the pilot, the gangplank was lowered and Hatusu, escorted by Senenmut, swept aboard, going directly to the gorgeously caparisoned cabin. Amerotke was ordered to join them, and Hatusu, smiling and joking like a girl at her first banquet, patted the cushions beside her and thrust a goblet of iced fruit juice into his hand. She leaned closer, her perfumed face laced with sweat, eyes bright with life.

âWe found it, Amerotke! The Book of Secrets. It lay beneath the paving stones in the centre of the old sanctuary. We found it and we burnt it.' Her smile faded. âNow go back to the House of Chains. Tomorrow I shall ensure justice is done.'

Â

The line of war chariots stirred restlessly. The horses, plumed and harnessed, moved backwards and forwards in their excitement; their drivers clicked their tongues, urging the magnificent beasts to stay calm. At least fifty chariots were there, the swiftest and fiercest of all Egypt's war squadrons. They had come out before dawn, silently leaving the city and moving to the edge of the Red Lands, a rocky dry wilderness where, in the grey light before dawn, the wind still stirred the dust devils. In the centre of the line was Hatusu, magnificent in the full war armour of Pharaoh. Next to her in the chariot was Senenmut. Amerotke and Shufoy occupied the place of honour in the chariot to her right. The judge rested against the rail and stared across the empty, desolate plain. He was weary, tired of all this. He wanted to take Norfret and his family back to his house, sit in the orchard and listen to the whirr of the crickets and the song of the birds, not be here, in the harsh wilderness, waiting for a man to die.

Before he had left Thebes, Amerotke had visited the House of Chains, as was his duty, to witness Lupherna drink the poisoned wine. She had gulped it quickly, then lay down and, without a murmur of protest, slipped into death. Now it was Menna's turn. He would die in this place, imprisoned in the great thorn bush which sprouted amongst a cluster of rocks some ten yards away. He had already been bound in a sheepskin, his mouth gagged, eyes blazing with fury. In front of the line of chariots the hawk-masked executioner watched as his assistants thrust the prisoner, still struggling, into the centre of the thorn bush to be cut and lacerated by its spiky thorns. Ropes were wound tightly around the bush, which was so drenched in oil Amerotke could smell it from where he stood.

Hatusu grasped the reins and, talking softly, urged the chariot forward. Senenmut leaned down and took the blazing cresset torch from the executioner. The chariot picked up speed, the fiery pitch glowed, dancing in the breeze as the chariot charged towards the thorn bush then wheeled around it, once, twice, before Hatusu slowed down. She shouted something, then, grasping the torch, flung it at the bush. The flames caught hold, bursting into a raging fire. All watched as Chief Scribe Menna burnt, body and soul being consumed by fire.

Once the flames started to die down, Hatusu turned her chariot back towards the rest, reining in before them.

âLord Valu,' she called, pointing out towards the eastern Red Lands. âIn this scorching place a Libyan tribe holds four hesets, kidnapped from the Temple of Isis.' Despite the crackling of the fire and the whipping breeze, Hatusu's voice carried full and strong. âIn the olden days,' she continued, âGreat Mother Isis would dispatch her assassins to right a wrong. You will lead an embassy and seek out that Libyan tribe. Tell them the Great Mother has loosed her assassins to bring justice to the Kingdom of the Two Lands and the People of the Nine Bows. Tell them, negotiate with them,

but you shall bring those four captives home.' She moved her chariot closer, in front of Amerotke. âAs for you, my lord, chosen of Isis, go back to the palace, take your wife home, and rejoice that Ma'at has been restored.'

but you shall bring those four captives home.' She moved her chariot closer, in front of Amerotke. âAs for you, my lord, chosen of Isis, go back to the palace, take your wife home, and rejoice that Ma'at has been restored.'

KERH: ancient Egyptian, âdarkness'

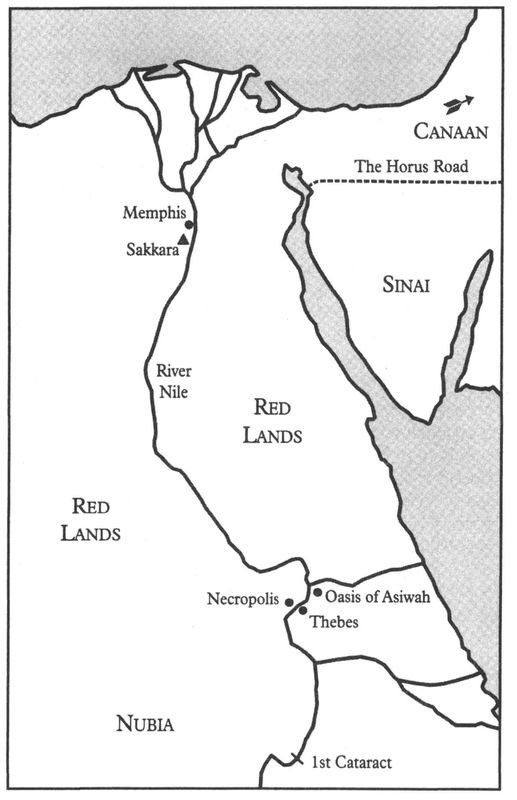

EGYPT C.1478 BC

The first dynasty of ancient Egypt was established about 3100 BC. Between that date and the rise of the New Kingdom (1550 BC) Egypt went through a number of radical transformations which witnessed the building of the pyramids, the creation of cities along the Nile, the union of Upper and Lower Egypt and the development of the Egyptians' religion around Ra, the Sun God, and the cult of Osiris and Isis. Egypt had to resist foreign invasion, particularly by the Hyksos, Asiatic raiders, who cruelly devastated the kingdom.

By 1479 BC, Egypt, pacified and united under Pharaoh Tuthmosis II, was on the verge of a new and glorious ascendancy. The Pharaohs had moved their capital to Thebes; burial in the pyramids was replaced by the development of the Necropolis on the west bank of the Nile as well as the exploitation of the Valley of the Kings as a royal mausoleum.

I have, to clarify matters, used Greek names for cities, etc., e.g. Thebes and Memphis, rather than their archaic Egyptian names. The place name Sakkara has been used to describe the entire pyramid complex around Memphis and Giza. I have also employed the shorter version for the Pharaoh Queen: i.e. Hatusu rather than Hatshepsut. Tuthmosis II died in 1479 BC and, after a period of confusion,

Hatusu held power for the next twenty-two years. During this period Egypt became an imperial power and the richest state in the world.

Hatusu held power for the next twenty-two years. During this period Egypt became an imperial power and the richest state in the world.

Egyptian religion was also being developed, principally the cult of Osiris, killed by his brother, Seth, but resurrected by his loving wife, Isis, who gave birth to their son, Horus. These rites must be placed against the background of the Egyptians' worship of the Sun God and their desire to create a unity in their religious practices. The Egyptians had a deep sense of awe for all living things: animals and plants, streams and rivers were all regarded as holy, while Pharaoh, their ruler, was worshipped as the incarnation of the divine will.

By 1479 BC the Egyptian civilisation expressed its richness in religion, ritual, architecture, dress, education and the pursuit of the good life. Soldiers, priests and scribes dominated this civilisation, and their sophistication is expressed in the terms they used to describe both themselves and their culture. For example, Pharaoh was âthe Golden Hawk'; the treasury was âthe House of Silver'; a time of war was âthe Season of the Hyaena'; a royal palace was âthe House of a Million Years'. Despite the country's breathtaking, dazzling civilisation, however, Egyptian politics, both at home and abroad, could be violent and bloody. The royal throne was always the centre of intrigue, jealousy and bitter rivalry. It was on to this political platform, in 1479 BC, that the young Hatusu emerged.

By 1478 BC Hatusu had confounded her critics and opponents, both at home and abroad. She had won a great victory in the north against the Mitanni and purged the royal circle of any opposition led by the Grand Vizier Rahimere. A remarkable young woman, Hatusu was supported by her wily and cunning lover, Senenmut, also her First Minister. Hatusu was determined that all sections of Egyptian society accept her as Pharaoh Queen of Egypt.

Egyptian society was bound up with life after death. The

ancient Egyptians did not have the modern fear of what lay beyond death. They saw it as an adventure, as a journey into a land more wonderful, a paradise under the rule of the Lord Osiris. They talked of âgoing into the Far West', and it was the duty of every Egyptian to prepare himself for this next stage of his existence. The journey, however, would have its perils. The dead would have to travel through the Underworld and into the Hall of Judgement, where their souls would be weighed in the Scales of Truth. The ancient Egyptians saw the heart as the symbol of the soul. Only those with a clean heart would be allowed into the Eternal Fields of the Blessed. The journey, therefore, posed its own dangers, but these could be overcome or circumvented if certain rituals were followed. The body had to be embalmed, purified and buried according to the Osirian Rite.

ancient Egyptians did not have the modern fear of what lay beyond death. They saw it as an adventure, as a journey into a land more wonderful, a paradise under the rule of the Lord Osiris. They talked of âgoing into the Far West', and it was the duty of every Egyptian to prepare himself for this next stage of his existence. The journey, however, would have its perils. The dead would have to travel through the Underworld and into the Hall of Judgement, where their souls would be weighed in the Scales of Truth. The ancient Egyptians saw the heart as the symbol of the soul. Only those with a clean heart would be allowed into the Eternal Fields of the Blessed. The journey, therefore, posed its own dangers, but these could be overcome or circumvented if certain rituals were followed. The body had to be embalmed, purified and buried according to the Osirian Rite.

Beyond the grave the dead would need goods, servants, food and drink, and these were buried with them. The Necropolis on the west bank of the Nile offered a wide range of funereal goods, and the ancient Egyptians travelled there, on what we would term their holidays, to inspect the coffins, caskets and other paraphernalia. The priests of the various temples also did a roaring trade; their prayers were essential both before and after death to ensure everything went well. There was no exception to this rule; it was all-encompassing, from the lowliest peasant to the Keeper of the Great House, Pharaoh himself. Indeed, part of the succession rite was that a Pharaoh had to supervise the funeral of his predecessor and then ensure that the royal tombs and sepulchres were carefully preserved and protected.

The discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in the 1920s illustrates what treasure houses these royal sepulchres truly were. They literally contained a king's ransom in precious goods, from alabaster jars to beds, couches and chariots. The temptation to steal is as ancient as the world itself, and it is only logical that the exact location of these tombs

was regarded as a state secret. Royal architects went to great lengths to conceal entrances, and even placed traps to catch the unwary. Nevertheless, the lure of such riches was irresistible. We know from contemporary sources that one night's raid could make the lucky thief a millionaire. Of course, getting into a tomb, stealing the goods and transporting them away carried its own hideous risks. If a thief was caught he could expect little mercy and would face an excruciating death, impaled alive, either on the cliffs above Thebes or at the entrances to the royal valleys. Nevertheless, there were always those cunning and greedy enough to try their luck. The Pharaohs saw such pillaging as a direct attack upon themselves and their own greatness and strength. The Valley of the Kings and the other royal sepulchres are now a great tourist attraction, but in the reign of Hatusu they were also the scene of a deadly game of cat and mouse â¦

was regarded as a state secret. Royal architects went to great lengths to conceal entrances, and even placed traps to catch the unwary. Nevertheless, the lure of such riches was irresistible. We know from contemporary sources that one night's raid could make the lucky thief a millionaire. Of course, getting into a tomb, stealing the goods and transporting them away carried its own hideous risks. If a thief was caught he could expect little mercy and would face an excruciating death, impaled alive, either on the cliffs above Thebes or at the entrances to the royal valleys. Nevertheless, there were always those cunning and greedy enough to try their luck. The Pharaohs saw such pillaging as a direct attack upon themselves and their own greatness and strength. The Valley of the Kings and the other royal sepulchres are now a great tourist attraction, but in the reign of Hatusu they were also the scene of a deadly game of cat and mouse â¦

Other books

Silo 49: Deep Dark by Ann Christy

Sweet Jealousy by Morgan Garrity

Indwell (Chasing Natalie's Ghosts) by Nicole Smith

Grayson: A Bad Boy Romance by Love, Amy

Valerie's Russia by Sara Judge

Krampus: The Three Sisters (The Krampus Chronicles Book 1) by Halbach, Sonia

Without Limits: Austin (Rugged Riders Book 4) by Ambrielle Kirk

The Gentlewoman by Lisa Durkin

Dead Man Walking by Paul Finch

Conquering William by Sarah Hegger