The Assassins (11 page)

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #History, #World, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #Religion, #Islam, #Shi'A

The vengeance of the Ismailis was not long delayed. Two fida'is wormed their way into the vizier's household in the guise of grooms, and by their skill and their display of piety gained his confidence. They found their opportunity when the vizier summoned them to his presence, to choose two Arab horses as a gift for the Sultan on the Persian New Year. The murder took place on i6 March 1127. `He did good deeds and showed worthy intentions in fighting against them,' said Ibn al-Athir, `and God granted him martyrdom.'2 The same historian records a punitive expedition by Sanjar against Alamut, in which more than 10,000 Ismailis perished. This is not mentioned by Ismaili or other sources, and is probably an invention.

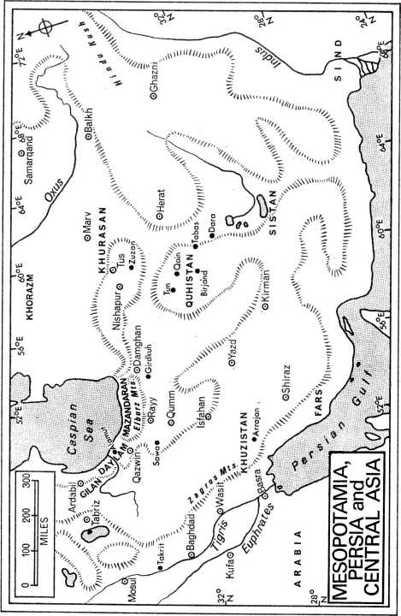

The end of hostilities found the Ismailis rather stronger than before. In Rudbar, they had reinforced their position by building a new and powerful fortress, called Maymundiz,3 and had extended their territory, notably by acquiring Talaqan. In the East, Ismaili forces, presumably from Quhistan, raided Sistan in 1129.4 In the same year Mahmud, the Seljuq Sultan of Isfahan, found it prudent to discuss peace, and invited an envoy from Alamut. Unfortunately the envoy, with a colleague, was lynched by the Isfahan mob when he left the Sultan's presence. The Sultan apologized and disclaimed responsibility but, understandably, refused Buzurgumid's request to punish the murderers. The Ismailis responded by attacking Qazvin, where, according to their own chronicle, they killed four hundred people and took enormous booty. The Qazvinis tried to fight hack, but, says the Ismaili chronicler, when the comrades killed one Turkish emir, the rest of them fled.s An attack on Alamut by Mahmud himself at this time failed to achieve any result.

In 1' 31 Sultan Mahmud died, and the usual wrangle followed between his brothers and his son. Some of the emirs managed to involve the Caliph of Baghdad, al-Mustarshid, in an alliance against Sultan Masud, and in 1139 the Caliph, with his vizier and a number of his dignitaries, was captured by Masud near Hamadan. The Sultan took his distinguished captive to Maragha, where he is said to have treated him with respect - but did not prevent a large group of Ismailis from entering the camp and murdering him. An Abbasid Caliph - the titular head of Sunni Islam - was an obvious objective for the daggers of the assassins if opportunity arose, but rumour accused Masud of complicity or deliberate negligence, and even charged Sanjar, still the nominal overlord of the Seljuq rulers, as an instigator of the crime. Juvayni tries hard to exonerate both of them from these charges: `Some of the more short-sighted and ill-wishers to the House of Sanjar accused them of responsibility for this act. But "the astrologers lied, by the Lord of the Ka'ba!" The goodness of Sultan Sanjar's character and the purity of his nature as instanced in his following and strengthening the Hanafite faith and the Shari'a [holy law], his respect for all that related to the Caliphate as also his mercy and compassion are too plain and evident for the like false and slanderous charges to be laid against his person, which was the source of clemency and the fountain-head of pity.' 6

In Alamut, the news of the Caliph's death was received with exultation. They celebrated for seven days and nights, made much of the comrades, and reviled the name and emblems of the Abbasids.

The list of assassinations in Persia during the reign of Buzurgumid is comparatively short, though not undistinguished. Besides the Caliph, the victims include a prefect of Isfahan, a governor of Maraglia, murdered not long before the arrival of the Caliph in that city, a prefect of Tabriz, and a mufti of Qazvin.

The slackening in the pace of assassination is not the only change in the character of the Ismaili principality. Unlike Hasan-i Sabbah, Buzurgumid was a local man in Rudbar, not a stranger; he had not shared Hasan's experience as a secret agitator, but had spent most of his active life as a ruler and administrator. His adoption of the role of a territorial ruler, and his acceptance by others as such, are strikingly demonstrated by the flight to Alamut, with his followers, of the emir Yarankush, an old and redoubtable enemy of the Ismailis, when he was displaced by the rising power of the Khorazmshah (Shah of Khorazm). The Shah asked for their surrender, arguing that he had been a friend of the Ismailis, while Yarankush had been their enemy - but Buzurgumid refused to hand them over, saying: `I cannot reckon as an enemy anyone who places himself under my protection.'? The Ismaili chronicler of the reign of Buzurgumid takes an obvious delight in recounting such stories of magnanimity - stories that reflect the role of a chivalrous lord rather than a revolutionary leader.

The Ismaili ruler fulfilled this role even to the point of suppressing heresy. In 1131, says the Ismaili chronicler, a Shiite called Abu Hashim appeared in Daylam and sent letters as far away as Khurasan. `Buzurgumid sent him a letter of advice, drawing his attention to the proofs of God.' Abu Hashim replied: `What you say is unbelief and heresy. If you come here and we discuss it, the falsity of your beliefs will become apparent.' The Ismailis sent an army against him, and defeated him. `They caught Abu Hashim, supplied him with ample proof, and burned him.'$

The long reign of Buzurgumid ended with his death on 9 February I138. As Juvayni elegantly puts it: `Buzurgumid remained seated on the throne of Ignorance ruling over Error until the 26th of Jumada I, 532 [9 February 1138], when he was crushed under the heel of Perdition and Hell was heated with the fuel of his carcase.'9 It is significant of the changing nature of Ismaili leadership that he was succeeded without incident by his son Muhammad, whom he had nominated as heir only three days before his death. When Buzurgumid died, says the Ismaili chronicler, `their enemies became joyful and insolent','° but they were soon made to realize that their hopes were vain.

The first victim of the new reign was another Abbasid - the ex-Caliph al-Rashid, the son and successor of the murdered al-Mustarshid. Like his father, he had become involved in Seljuq disputes, and had been solemnly deposed by an assembly of judges and jurists convened by the Sultan. Al-Rashid had then left Iraq for Persia, to join his allies, and was in Isfahan, recuperating from an illness, when his assassins found him on S or 6 June 1138. The murderers were Khurasanis in his own service. The death of a caliph was again celebrated with a week of rejoicing at Alamut, in honour of the first `victory' of the new reign.-

The role of honour for the reign of Muhammad lists in all fourteen assassinations. Besides the Caliph, the most notable victim was the Seljuq Sultan Da'ud, murdered by four Syrian assassins in Tabriz in 1143. It was alleged that the murderers had been sent by Zangi, the ruler of Mosul, who was expanding his realm into Syria and feared that Da'ud might be sent to replace him. It is certainly curious that a murder in North Western Persia should have been arranged from Syria and not from near-by Alamut. Other victims include an emir at Sanjar's court and one of his associates, a prince of the house of the Khorazmshahs, local rulers in Georgia (?) and Mazandaran, a vizier, and the Qadis of Quhistan, Tiflis and Hamadan, who had authorized or instigated the killing of Ismailis.

It It was a meagre haul compared with the great days of Hasan-i Sabbah, and reflects the growing concern of the Ismailis with local and territorial problems. In the Ismaili chronicle these take pride of place. The great affairs of the Empire are hardly mentioned; instead, there are circumstantial accounts of local conflicts with neighbouring rulers, embellished with lists of the cows, sheep, asses and other booty taken. The Ismailis more than held their own in a series of raids and counter-raids between Rudbar and Qazvin, and in 1143 repelled an attack by Sultan Mahmud on Alamut. They managed to gain or build some new fortresses in the Caspian districts, and are even reported to have extended their activities to two new areas - in Georgia, where they raided and carried on propaganda, and in present-day Afghanistan, where they were invited by the ruler, for reasons of his own, to send a mission. On his death in IIGI both missionaries and converts were put to death by his successor.

Two enemies were specially persistent - the ruler of Mazandaran, and Abbas, the Seljuq governor of Rayy, who organized a massacre of Ismailis in that city and attacked the Ismaili territories. Both are said to have built towers of Ismaili skulls. In 1146 or i 147 Abbas was murdered by Sultan Masud while on a visit to Baghdad, `on a sign', says the Ismaili chronicler, `from Sultan Sanjar'.1z His head was sent to Khurasan. There are several such indications that Sanjar and the Ismailis are on the same side, though at other times they came into conflict, as for example when Sanjar supported an attempt to restore the Sunni faith in one of the Ismaili centres in Quhistan. There as elsewhere, the issues involved are usually local and territorial. It is noteworthy that in the other Ismaili castles and seignories, besides Alamut, leadership descended from father to son, and often the conflicts in which they are engaged are purely dynastic.

The passion seemed to have gone out of Ismailism. In the virtual stalemate and tacit mutual acceptance between the Ismaili principalities and the Sunni monarchies, the great struggle to overthrow the old order and establish a new millennium, in the name of the hidden Imam, had dwindled into border-squabbles and cattle-raids. The castle strongholds, originally intended to be the spearheads of a great onslaught on the Sunni Empire, had become the centres of local sectarian dynasties, of a type not uncommon in Islamic history. The Ismailis even had their own mint, and struck their own coins. True, the fida'is still practised murder, but this was not peculiar to them, and in any case hardly sufficed to fire the hopes of the faithful.

Among them there were still some who harked back to the glorious days of Hasan-i Sabbah - to the dedication and adventure of his early struggles, and the religious faith that inspired them. They found a leader in Hasan, the son and heir apparent of the lord of Alamut, Muhammad. His interest began early. `When he had nearly approached the age of discretion he conceived the desire to study and examine the teachings of Hasan-i Sabbah and his own forefathers; and ... he came to excel in the exposition of their creed ... With ... the eloquence of his words he won over the greater part of that people. Now his father being altogether lacking in that art, his son . . . appeared a great scholar beside him, and therefore ... the vulgar sought to follow his lead. And not having heard the like discourses from his father they began to think that here was the Imam that had been promised by Hasan-i Sabbah. The people's attachment to him increased and they made haste to follow him as their leader.'

Muhammad did not like this at all. A conservative in his Ismailism, he was rigid in his observance of the principles laid down by his father and Hasan[-i Sabbah] with regard to the conduct of propaganda on behalf of the Imam and the outward observance of Muslim practices; and he considered his son's behaviour to be inconsistent with those principles. He therefore denounced him roundly and having assembled the people spoke as follows: "This Hasan is my son, and I am not the Imam but one of his dais. Whoever listens to these words and believes them is an infidel and atheist." And on these grounds he punished some who had believed in his son's Imamate with all manner of tortures and torments, and on one occasion put 250 persons to death on Alamut and then binding their corpses on the backs of :50 others condemned on the same charge he expelled these latter from the castle. And in this way they were discouraged and suppressed.'- 3Hasan bided his time, and managed to dispel his father's suspicions. On Muhammad's death in i 162 he succeeded him without opposition. He was then about 35 years old.

Hasan's rule was at first uneventful, marked only by a certain relaxation in the rigorous enforcement of the Holy Law that had previously been maintained at Alamut. Then, two and a half years after his accession, in the middle of the fasting month of Ramadan, he proclaimed the millennium.

Ismaili accounts of what happened are preserved in the later literature of the sect and also, in a somewhat modified form, in the Persian chronicles written after the fall of Alamut. They tell a curious tale. On the 17th day of the month of Ramadan, of the year 5 59 [8 August z 164], under the ascendancy of Virgo and when the sun was in Cancer, Hasan ordered the erection of a pulpit in the courtyard of Alamut, facing towards the west, with four great banners of four colours, white, red, yellow, and green, at the four corners. The people from the different regions, whom he had previously summoned to Alamut, were assembled in the courtyard - those from the East on the right side, those from the West on the left side, and those from the North, from Rudbar and Daylam, in front, facing the pulpit. As the pulpit faced west the congregants had their backs towards Mecca. `Then,' says an Ismaili tract, `towards noon, the Lord [Hasan], on his mention be peace, wearing a white garment and a white turban, came down from the castle, approached the pulpit from the right side, and in the most perfect manner ascended it. Three times he uttered greetings, first to the Daylamis, then to those on the right, then to those on the left. In a moment lie sat down, and then rose up again and, holding his sword, spoke in a loud voice.' Addressing himself to `the inhabitants of the worlds, jinn, men, and angels', he announced that a message had come to him from the hidden Imam, with new guidance. `The Imam of our time has sent you his blessing and his compassion, and has called you his special chosen servants. He has freed you from the burden of the rules of Holy Law, and has brought you to the Resurrection.' In addition, the Imam named Hasan, the son of Muhammad, the son of Buzurgumid, as `our vicar, da'i and proof. Our party must obey and follow him both in religious and worldly matters, recognize his commands as binding, and know that his word is our word.' I 4 When he had completed his address, Hasan stepped down from the pulpit, and performed two prostrations of the festival prayer. Then, a table having been laid, he invited them to break their fast, join in a banquet, and make merry. Messengers were sent to carry the glad tidings to east and west. In Quhistan, the chief of the fortress of Mu'minabad repeated the ceremony of Alamut, and proclaimed himself as the vicar of Hasan, from a pulpit facing the wrong way; `And that day on which these ignominies were divulged and these evils proclaimed in that nest of heretics, Mu'minabad, that assembly played harp and rebeck and openly drank wine upon the very steps of that pulpit and within its precincts.'I 5 In Syria too the word was received, and the faithful celebrated the end of the law.

Other books

Lt. Leary, Commanding by David Drake

Bone and Blood by Margo Gorman

Everlasting Light - A Civil War Romance Novella by Andrea Boeshaar

How Literature Saved My Life by David Shields

One Good Man by Alison Kent

Different Roads by Clark, Lori L.

Karen D. Badger - Yesterday Once More by Karen D. Badger

The Garden of Lost and Found by Dale Peck

Rising, Freestyle: Xtreme Adventures, Book 2 by Vivian Arend

B00724AICC EBOK by Gallant, A. J.