The Ascent of Man (5 page)

Authors: Jacob Bronowski

Fossils that recount the cultural evolution of man in an orderly progression.

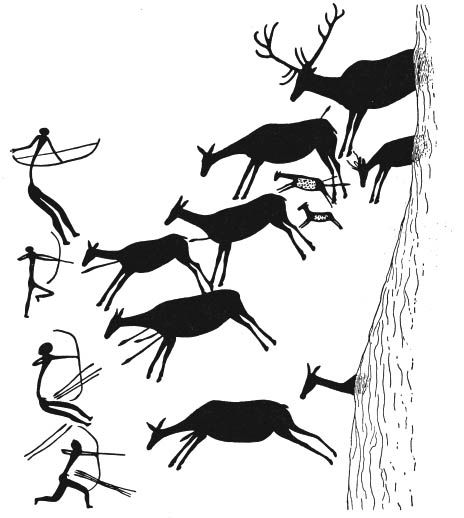

Fossils that recount the cultural evolution of man in an orderly progression.Rock painting of a reindeer hunt, Los Caballos Shelter, Valtorta Gorge, Castellon, Eastern Spain. The invention of the bow and arrow came at the end of the last Ice Age

.

The transhumance way of life is itself a cultural fossil now, and has barely survived. The only people that still live in this way are the Lapps in

the extreme north of Scandinavia, who follow the reindeer as they did during the Ice Age. The ancestors of the Lapps may have come north from the Franco-Cantabrian cave area of the Pyrenees in the wake of the reindeer as the last icecaps retreated from southern Europe twelve thousand years ago. There are thirty thousand people and three hundred thousand reindeer, and their way of life is coming to

an end even now. The herds go on their own migration across the fiords from one icy pasture of lichen to another, and the Lapps go with them. But the Lapps are not herdsmen; they do not control the reindeer, they have not domesticated it. They simply move where the herds move.

Even though the reindeer herds are in effect still wild, the Lapps have some of the traditional inventions for controlling

single animals that other cultures also discovered: for example, they make some males manageable as draught animals by castrating them. It is a strange relationship. The Lapps are entirely dependent on the reindeer – they eat the meat, a pound a head each every day, they use the sinews and fur and hides and bones, they drink the milk, they even use the antlers. And yet the Lapps are freer than

the reindeer, because their mode of life is a cultural adaptation and not a biological one. The adaptation that the Lapps have made, the transhumance life on the move in a landscape of ice, is a choice that they can change; it is not irreversible, as biological mutations are. For a biological adaptation is an inborn form of behaviour; but a culture is a learned form of behaviour – a communally

preferred form, which (like other inventions) has been adopted by a whole society.

There lies the fundamental difference between a cultural adaptation and a biological one; and both can be demonstrated in the Lapps. Making a shelter from reindeer hides is an adaptation that the Lapps can change tomorrow – most of them are doing so now. By contrast the Lapps, or human lines ancestral to them,

have also undergone a certain amount of biological adaptation. The biological adaptations in

Homo sapiens

are not large; we are a rather homogeneous species, because we spread so fast over the world from a single centre. Nevertheless biological differences do exist between groups of men, as we all know. We call them racial differences, by which we mean exactly that they cannot be changed by a

change of habit or habitat. You cannot change the colour of your skin. Why are the Lapps white? Man began with a dark skin; the sunlight makes vitamin D in his skin, and if he had been white in Africa, it would make too much. But in the north, man needs to let in all the sunlight there is to make enough vitamin D, and natural selection therefore favoured those with whiter skins.

The biological

differences between different communities are on this modest scale. The Lapps have not lived by biological adaptation but by invention: by the imaginative use of the reindeer’s habits and all its products, by

turning it into a draught animal, by artefacts and the sledge. Surviving in the ice did not depend on skin colour; the Lapps have survived, man survived the Ice Ages, by the master invention

of all – fire.

Fire is the symbol of the hearth, and from the time

Homo sapiens

began to leave the mark of his hand thirty thousand years ago, the hearth was the cave. For at least a million years man, in some recognisable form, lived as a forager and a hunter. We have almost no monuments of that immense period of prehistory, so much longer than any history that we record. Only at the end of

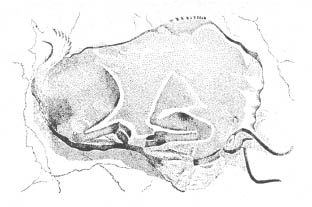

that time, on the edge of the European ice-sheet, we find in caves like Altamira (and elsewhere in Spain and southern France) the record of what dominated the mind of man the hunter. There we see what made his world and preoccupied him. The cave paintings, which are about twenty thousand years old, fix for ever the universal base of his culture then, the hunter’s knowledge of the animal that he lived

by and stalked.

We find in caves like Altamira the record of what dominated the mind of man the hunter. I think that the power we see expressed here for the first time is the power of anticipation: the forward-looking imagination.

We find in caves like Altamira the record of what dominated the mind of man the hunter. I think that the power we see expressed here for the first time is the power of anticipation: the forward-looking imagination.Recumbent bison

.

One begins by thinking it odd that an art as vivid as the cave paintings should be, comparatively, so young and so rare. Why are there not more monuments to man’s visual

imagination, as there are to his invention? And yet when we reflect, what is remarkable is not that there are so few monuments, but that there are any at all. Man is a puny, slow, awkward, unarmed animal – he had to invent a pebble, a flint, a knife, a spear. But why to these scientific inventions, which were essential to his survival, did he from an early time add those arts that now astonish

us: decorations with animal shapes? Why, above all, did he come to caves like this, live in them, and then make paintings of animals not where he lived but in places that were dark, secret, remote, hidden, inaccessible?

The obvious thing to say is that in these places the animal was magical. No doubt that is right; but magic is only a word, not an answer. In itself, magic is a word which explains

nothing. It says that man believed he had power, but what power? We still want to know what the power was that the hunters believed they got from the paintings.

Here I can only give you my personal view. I think that the power that we see expressed here for the first time is the power of anticipation: the forward-looking imagination. In these paintings the hunter was made familiar with dangers

which he knew he had to face but to which he had not yet come. When the hunter was brought here into the secret dark and the light was suddenly flashed on the pictures, he saw the bison as he would have to face him, he saw the running deer, he saw the turning boar. And he felt alone with them as he would in the hunt. The moment of fear was made present to him; his spear-arm flexed with an experience

which he would have and which he needed not to be afraid of. The painter had frozen the moment of fear, and the hunter entered it through the painting as if through an air-lock.

For us, the cave paintings re-create the hunter’s way of life as a glimpse of history; we look through them into the past. But for the hunter, I suggest, they were a peep-hole into the future; he looked ahead. In either

direction, the cave paintings act as a kind of telescope tube of the imagination: they direct the mind from what is seen to what can be inferred or conjectured. Indeed, this is so in the very action of painting; for all its superb observation, the flat picture only means something to the eye because the mind fills it out with roundness and movement, a reality by inference, which is not actually

seen but is imagined.

Art and science are both uniquely human actions, outside the range of anything that an animal can do. And here we see that they derive from the same human faculty: the ability to visualise the future, to foresee what may

happen and plan to anticipate it, and to represent it to ourselves in images that we project and move about inside our head, or in a square of light on

the dark wall of a cave or a television screen.

We also look here through the telescope of the imagination; the imagination is a telescope in time, we are looking back at the experience of the past. The men who made these paintings, the men who were present, looked through that telescope forward. They looked along the ascent of man because what we call cultural evolution is essentially a constant

growing and widening of the human imagination.

The men who made the weapons and the men who made the paintings were doing the same thing – anticipating a future as only man can do, inferring what is to come from what is here. There are many gifts that are unique in man; but at the centre of them all, the root from which all knowledge grows, lies the ability to draw conclusions from what we see

to what we do not see, to move our minds through space and time, and to recognise ourselves in the past on the steps to the present. All over these caves the print of the hand says: ‘This is my mark. This is man.’

THE HARVEST OF THE SEASONS

The history of man is divided very unequally. First there is his biological evolution: all the steps that separate us from our ape ancestors. Those occupied some millions of years. And then there is his cultural history: the long swell of civilisation that separates us from the few surviving hunting tribes of Africa, or from the food-gatherers of Australia.

And all that second, cultural gap is in fact crowded into a few thousand years. It goes back only about twelve thousand years – something over ten thousand years, but much less than twenty thousand. From now on I shall only be talking about those last twelve thousand years which contain almost the whole ascent of man as we think of him now. Yet the difference between the two numbers, that is, between

the biological time-scale and the cultural, is so great that I cannot leave it without a backward glance.

It took at least two million years for man to change from the little dark creature with the stone in his hand,

Australopithecus

in Central Africa, to the modern form,

Homo sapiens

. That is the pace of biological evolution – even though the biological evolution of man has been faster than

that of any other animal. But it has taken much less than twenty thousand years for

Homo sapiens

to become the creatures that you and I aspire to be: artists and scientists, city builders and planners for the future, readers and travellers, eager explorers of natural fact and human emotion, immensely richer in experience and bolder in imagination than any of our ancestors. That is the pace of

cultural evolution; once it takes off, it goes as the ratio of those two numbers goes, at least a hundred times faster than biological evolution.

Once it takes off: that is the crucial phrase. Why did the cultural changes that have made man master of the

earth begin so recently? Twenty thousand years ago man in all parts of the world that he had reached was a forager and a hunter, whose most

advanced technique was to attach himself to a moving herd as the Lapps still do. By ten thousand years ago that had changed, and he had begun in some places to domesticate some animals and to cultivate some plants; and that is the change from which civilisation took off. It is extraordinary to think that only in the last twelve thousand years has civilisation, as we understand it, taken off. There

must have been an extraordinary explosion about 10,000

BC

– and there was. But it was a quiet explosion. It was the end of the last Ice Age.

We can catch the look and, as it were, the smell of the change in some glacial landscape. Spring in Iceland replays itself every year, but it once played itself over Europe and Asia when the ice retreated. And man, who had come through incredible hardships,

had wandered up from Africa over the last million years, had battled through the Ice Ages, suddenly found the ground flowering and the animals surrounding him, and moved into a different kind of life.

It is usually called the ‘agricultural revolution’. But I think of it as something much wider, the biological revolution. There was intertwined in it the cultivation of plants and the domestication

of animals in a kind of leap-frog. And under this ran the crucial realisation that man dominates his environment in its most important aspect, not physically but at the level of living things – plants and animals. With that there comes an equally powerful social revolution. Because now it became possible – more than that, it became necessary – for man to settle. And this creature that had roamed

and marched for a million years had to make the crucial decision: whether he would cease to be a nomad and become a villager. We have an anthropological record of the struggle of conscience of a people who make this decision: the record is the Bible, the Old Testament. I believe that civilisation rests on that decision. As for people who never made it, there are few survivors. There are some nomad

tribes who still go through these vast transhumance journeys from one grazing ground to another: the Bakhtiari in Persia, for example. And you have actually to travel with them and live with them to understand that civilisation can never grow up on the move.