The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (16 page)

Authors: Brett McKay

To those who persevere only by fits and starts—now hot, now cold—we would say, “Never give up.” Do not lose courage or grow weary. Slow as the tortoise crept, he reached the goal before the sleeping hare. If you cannot run, walk; if you cannot fly, plod. Plodding, humble as it seems, has done wonders, and will do more yet. Consider, furthermore, that when the reward comes, it is scarcely ever such as we had anticipated. We may have aimed at getting rich; the riches do not come. But, instead thereof, we find ourselves rich in mind; conscious of having striven manfully to do the duty that lay before us, and in so doing have armed ourselves with a reliant spirit, which passes by small trials, and looks on great ones with calm courage. View it as we will, the conclusion is inevitable, that perseverance is its own reward.

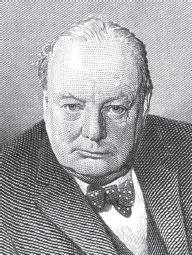

During the Fall of France

On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. On the same day, the Prime Minister of Britain, Neville Chamberlain, resigned and was replaced by Winston Churchill. On the 13th, Churchill made his first appearance before the House of Commons as the Head of Her Majesty’s Government. Despite receiving a tepid reception from that body, he issued a masterful call-to-arms, offering unshakeable resolve to a country frightened that it would be next to fall to German forces.

May 13, 1940

I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined the government: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: victory; victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realized; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forward towards its goal. But I take up my task with buoyancy and hope. I feel sure that our cause will not be suffered to fail among men. At this time I feel entitled to claim the aid of all, and I say, “Come then, let us go forward together with our united strength.”

After a devastating defeat in which British troops had to be evacuated from Dunkirk, France, Churchill once more sought to shore up his countrymen’s resolve to continue fighting.

June 4, 1940

I have, myself, full confidence that if all do their duty, if nothing is neglected, and if the best arrangements are made, as they are being made, we shall prove ourselves once again able to defend our Island home, to ride out the storm of war, and to outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary for years, if necessary alone. At any rate, that is what we are going to try to do. That is the resolve of His Majesty’s Government—every man of them. That is the will of Parliament and the nation. The British Empire and the French Republic, linked together in their cause and in their need, will defend to the death their native soil, aiding each other like good comrades to the utmost of their strength. Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.

“To think we are able is almost to be so; to determine upon attainment is frequently attainment itself. Thus earnest resolution has often seemed to have about it almost a savor of omnipotence.” —Samuel Smiles

F

ROM

A B

OOK OF

V

ERSES

, 1889

By William Ernest Henley

After contracting tuberculosis of the bone at age twelve, and having one leg amputated below the knee at age eighteen, doctors informed William Ernest Henley that they would have to amputate his other leg to save his life. Refusing to accept this diagnosis, the poet chose to be hospitalized for several years and endure numerous painful surgeries in order to save the leg. He penned this famous poem from his hospital bed, resolute in his determination to lead a full and vigorous life. That he did, eventually leaving the hospital with the leg intact and going on to become a successful and respected poet, critic, and literary editor.

Invictus, Latin for “unconquerable,” has become the watchword of every man who looks life’s challenges in the eye and refuses to blink.

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Concerning the Characteristic of Hardihood

F

ROM

H

OW TO

C

HOOSE THE

R

IGHT

V

OCATION

, 1917

By Holmes Whittier Merton

Hardihood is a manly trait that encompasses the boldness, confidence, and daring to attempt difficult and risky feats, as well as the grit and resiliency to keep going when faced with setbacks and criticism. These questions are designed to help you evaluate your personal level of hardihood.

Have I “stout and persistent courage” or am I only courageous under excitement or stimulation of some kind?

Do I have to screw up my courage to meet difficult situations?

Am I conscious of being mentally and physically rugged?

Do I challenge hardships or do I try to avoid hardships and difficulties by following “the line of least resistance?”

Do I hesitate about trying out my powers in unused directions that demand fortitude or courage?

Have I the courage to blaze new lines of action when success seems reasonably certain or do I wait until others have occupied the “strategic positions?”

Does the element of personal risk in sports, travel, adventures or vocations count greatly with me?

Does that which is unknown or untried affright or allure me?

Am I attracted or repelled by the hazardousness of life-saving callings?

Am I resolute and clear-headed in the presence of imminent danger or do I quail or become panic-stricken?

As boy or man, have I ever shown

individual

heroism or is my bravery always of the mass or mob kind?

Do I struggle to master matters that test all of my resources?

Can I stand and profit by severe criticism when I have been or seem to have been at fault?

Do I, if necessary, court severe discipline as a preparatory course for a desired vocation or do I pamper myself and like to be coddled by others?

Do I strive for personal efficiency, grasp at opportunities and recognize my right to advancement?

Do I rebound quickly from defeat?

Am I indifferent to supercilious fault-finding?

Do I enjoy being in contests of fortitude and endurance and in intellectual combats?

If I were a candidate for some elective office would defeat dishearten me or should I reckon each successive defeat as preparation for final victory?

When confronted with unexpected difficulties in anything that I have undertaken, is my first impulse, or reaction, the desire to back down or to go ahead with greater energy than before?

Do I stand by the presumption that I am to succeed, even when things look blackest?

Have I a persistent resolution when once a careful judgment has been made?

In making purchases—whether of neckties or machinery equipments—do I inspect the goods under consideration and form independent opinion of their merits or am I influenced unconsciously in my decisions by what I think the salesman may think of me?

Do I sometimes accept less than I know I should for services rendered because I lack the stamina to stand up for my rights?

“Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.” —Benjamin Franklin

F

ROM

S

ELF

-H

ELP

, 1876

By Samuel Smiles

The cultivation of this quality is of the greatest importance; resolute determination in the pursuit of worthy objects being the foundation of all true greatness of character. Energy enables a man to force his way through irksome drudgery and dry details, and carries him onward and upward in every station in life. It accomplishes more than genius, with not one-half the disappointment and peril. It is not eminent talent that is required to ensure success in any pursuit, so much as purpose—not merely the power to achieve, but the will to labour energetically and perseveringly. Hence energy of will may be defined to be the very central power of character in a man—in a word, it is the Man himself. It gives impulse to his every action, and soul to every effort. True hope is based on it—and it is hope that gives the real perfume to life. There is a fine heraldic motto on a broken helmet in Battle Abbey, “L’espoir est ma force” [“Hope is my strength”], which might be the motto of every man’s life. “Woe unto him that is faint-hearted,” says the son of Sirach. There is, indeed, no blessing equal to the possession of a stout heart. Even if a man fail in his efforts, it will be a great satisfaction to him to enjoy the consciousness of having done his best. In humble life nothing can be more cheering and beautiful than to see a man combating suffering by patience, triumphing in his integrity, and who, when his feet are bleeding and his limbs failing him, still walks upon his courage.