The Arrogance of Power (76 page)

Read The Arrogance of Power Online

Authors: Anthony Summers

Yet that is precisely what was to happen. The Nixon settlement offered more to the North Vietnamese, in a real sense, than had been foreseen in the Geneva accords of 1954. Then, the Communists had agreed to withdraw to the North. The arrangement Nixon accepted in 1973 permitted some 148,000 North Vietnamese troops to remain in the South, posing a grave threat to Saigon from the outset.

15

That, he admitted in old age, was the “biggest flaw” in the agreement.

North Vietnamese attacks began again almost immediately, attacks that were to culminate in 1975 with total victory over the South and the ignominious departure of those Americans left in Saigon.

Nixon would insist to his dying day that American military force could and should have been used again to rescue the South Vietnamese regime. The new attacks would have been summarily stopped, he argued, had his presidency not been weakened by Watergate, had the “stupid and shortsighted” Congress not set itself firmly against further military involvement. It is an argument, however, that fails to take into account the utter determination of the northerners to prevail.

“We won the war,” Nixon would still be claiming in 1992, “but lost the peace.” It was mere verbiage, as was his claim that the United States had achieved “peace with honor in Vietnam.” What the Christmas bombing of 1972 really achieved was to blast open an escape route from a predicament that, from the American point of view, had long since ceased to be tenable.

_____

To bomb during the holiday season, Nixon was to say, had been “the most difficult decision I made during the entire war . . .” “I suppose all the decisions are hard,” he had written in his diary, “but this one was heartrending.”

The president had Winston Churchill on his mind during this period, and on Christmas Eve his diary entry had been positively Churchillian:

This is December 24, 1972âKey Biscayneâ4

A

.

M

. The main thought that occurred to me at this early hour of the morning the day before Christmas, in addition to the overriding concern with regard to bringing the war to an end, is that I must get away from the thought of considering the office at any time a burden. . . . I think the term glorious burden is the best description.

On this day before Christmas it is God's great gift to me to have

the opportunity to exert leadership, not only for America but on the world scene. . . . this really begins a new period and this tape concludes with that thoughtâa period of always reminding myself of the glorious burden of the presidency.

Within months, in an address to the nation that was really an attempt to talk his way out of Watergate, Nixon would be using the Christmas air campaign as the banner of his personal suffering: “my terrible personal ordeal of the renewed bombing of North Vietnam.”

His ordeal took place in private, mostly in the peace and sunshine of Key Biscayne. Haldeman had no contact with the president for a full twelve days, an unprecedentedly long gap. He himself took a vacation in California, as did other senior staff, including for a while Henry Kissinger. So far as the press was concerned, as the UPI's White House correspondent Helen Thomas has recalled, the president was “in hiding.” He made no public appearances for eleven days, watched a lot of football on television, and took in six movies.

Nixon's true condition at that time can only be guessed at. His silence on the bombing, he was to claim, was out of a concern not to jeopardize negotiations. “But I also think,” Kissinger was to write later, “there were other, more complex reasons. Nixon was still seized by the withdrawn and sullen hostility that had dominated his mood since his electoral triumph.”

Others had more damning interpretations. Anthony Lewis of the

New York Times

accused the president of acting “like a maddened tyrant.” The

Washington Post

said millions of Americans were wondering at “their President's very sanity.” Republican senator William Saxbe thought Nixon had “left his senses on this issue.”

The

New York Times

's James Reston called the bombing offensive “war by tantrum”âand perhaps on good evidence. His colleague William Beecher, the

Times

's military correspondent, had filed a dispatch reporting that in the course of demanding renewed bombing, the president had been “throwing stuff against the wall.”

16

At dinner on the first night of the attack, Nixon had talked in an astonishing vein in front of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Moorer, Henry Kissinger, Teddy Roosevelt's daughter Alice Longworth, Pat and Julie, and the columnist Richard Wilson. He said, Wilson recalled, that he “did not care if the whole wide world thought he was crazy in resuming the bombing. If it did, so much the better. The Russians and Chinese might think they were dealing with a madman and so had better force North Vietnam into a settlement before the world was consumed in a larger war. . . .”

It was the Madman Theory again, four years after Nixon had first proposed frightening the Communists with the notion that the man with “his hand on the nuclear button” could not be restrained “when he's angry.”

17

_____

Two months earlier, before the November landslide, Haldeman had made a remarkable diary entry following a meeting with the president. Nixon, he noted, had “made the interesting point that after the election we will have awesome power with no discipline, that is, there won't be another election coming up to discipline us.”

One item on the agenda was revenge. “I want the most comprehensive notes on those that have tried to do us in,” Nixon had told John Dean. “. . . they didn't have to do it . . . they are asking for it and they are going to get it. . . . We have not used the power in this first four years. . . . We have never used it . . . things are going to change now.”

There were also grandiose plans for the future. Early in December, Nixon ordered immediate action on three political projects. He wanted his brother Edward to run for Congress in Washington State; Tricia's husband Edward Cox to run in New York; and Julie's husband David Eisenhower in Pennsylvania. Was he attempting to emulate the Kennedys and found a dynasty of his own?

During the Christmas recess Dean met for lunch with the chief counsel of the House Judiciary Committee, Jerome Zeifman. What did Zeifman think, Dean inquired, of Nixon's chances of persuading Congress to repeal the two-term limit on the presidency? “Sometimes,” Zeifman responded, “I wonder if your boss is demented.”

Life

's Hugh Sidey, an authority on the presidency, reported that after the election Nixon had gone “to the mountaintop at Camp David and read Arnold Toynbee for ideas about how to carry his administration to greater heights. He mused about how he might wage a campaign to rescind the 22

nd

Amendment and run for a third term.”

Should Nixon not succeed in extending his presidency, Jeb Magruder was to write, he intended to “control the Executive Branch of the government by establishing âa perpetual presidency.' He was so convinced that his kind of administration was better for the country than anything the Democrats could offer, that he wanted to be able to pick his successors.”

Nixon's choice as his heir, he told several people, was former Texas governor John Connally.

18

With him in the White House, Nixon hoped, he himself would retain effective control of foreign policy.

Such great expectations were nonetheless shot through with anxiety. “In the Oval Office that December of 1972 I saw a very troubled man,” recalled James Keogh, summoned by Nixon to discuss his appointment as director of the United States Information Agency. “I left the office concerned because I could see that he was troubled . . . he, as a perceptive man, already knew how serious the road ahead was for him.”

The president's fears, like those of his namesake who had reigned over fifteenth-century England, were driven by dreams and portents. Late in 1972, Ehrlichman remembered, “a strange shudderâa premonition?âwent through the people near the President. . . . He had been getting messages via Rose

Woods from Billy Graham and Jeane Dixon, among others, that his life was in danger. . . . the soothsayers had him worried.”

As early as a month after the Watergate arrests, Nixon himself had glimpsed the future and turned away. “I had a strange dream last night,” a recently released tape shows he confided to Haldeman. “It's going to be a nasty issue for a few days. I can't believe thatâwe're whistling in the darkâbut I can't believe that they can tie the thing to me. . . .”

40.

The palace guard, in the Oval Office. Bob Haldeman is in the foreground, John Ehrlichman at the far end of the table. Dwight Chapin

(standing)

thought his boss would be “the greatest president in history.”

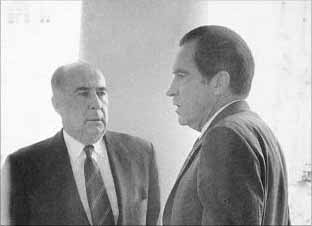

41.

The president with Attorney General John Mitchelle, his “political right arm.”

42.

An ally, and a deal. Nixon with Teamsters Union leader Frank Fitzsimmons. Fitzsimmons got a (conditional) pardon for his jailed predecessor, Jimmy Hoffa, while Teamsters money flowed to the Nixon White House.

43.

Hard hats on a table in the White Houseâthere was a special one for Nixonâduring a 1970 visit by construction workers' leaders. Their members had recently attacked antiwar demonstrators.