The Annals of Unsolved Crime (30 page)

Read The Annals of Unsolved Crime Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

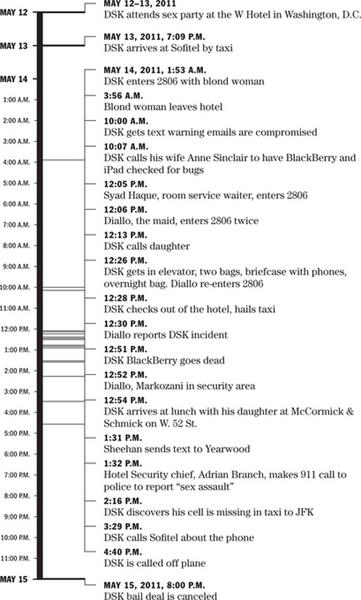

At 2:16 p.m. he called Camille, who had also just left the restaurant, on one of his spare BlackBerrys. He asked her to go back to the restaurant and search for his missing phone. CCTV footage at the restaurant shows her crawling under the table.

At 2:28 p.m., she sent him a text message saying that she could not find the phone. Meanwhile, as DSK continued on to the airport, he was still attempting to locate the missing phone. At 3:01 p.m., he was calling it from his spare phone. He received no answer.

What DSK did not know was that his phone had remained at the Sofitel after he had left the hotel. As late as 12:51 p.m., which was twenty-three minutes after DSK left the hotel, the GPS on the phone showed that it was still at the Sofitel, according to the records of BlackBerry parent company Research In Motion. The company could determine this time because a BlackBerry, like many other smartphones, continues to send a signal as to its location even when it is turned off. BlackBerry could also electronically determine that the GPS signals on DSK’s phone had abruptly stopped at 12:51, indicating either that the battery had run out or that the GPS had been intentionally disabled. (A forensic expert later concluded from the strength of the previous signals that the latter most likely occurred.) So, either the phone was still in the presidential suite or someone at the hotel had taken it from the Sofitel after 12:51 p.m. (when it was no longer traceable).

At 3:29 p.m., evidently still unaware of what was happening at the Sofitel, DSK called the hotel from the taxi, saying, according to the police transcript, “I am Dominique Strauss-Kahn, I was a guest. I left my phone behind.” He then said he was in room “2806.”

At that time, Diallo had just left the hotel en route to St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital to be examined, but the police were still at the hotel. DSK was asked to give a phone number, so that he could be called back after someone searched for his phone. He furnished it.

At 3:33 p.m., police and security staff, using a security electronic key, then reentered the presidential suite. The police did not find the phone.

When DSK was called back thirteen minutes later, he spoke to a hotel employee who was in the presence of police detective John Mongiello. The hotel employee falsely told him that his phone had been found (it has never been found) and asked where it could be delivered. DSK told him that he was at JFK airport and said, “I have a problem because my flight leaves at 4:26 p.m.” He was reassured that someone could bring it to the airport in time.

“OK, I am at the Air France terminal, gate four, flight twenty-three,” DSK responded. At 4:45 p.m., the police called DSK off the plane and took him into custody. He was then driven back to New York City.

The police arrived on the scene at the Sofitel at 2:05 p.m. Two uniformed policemen can be seen on the CCTV video. They walked through the main lobby to the security area, where they were greeted by the hotel’s manager, Florian Shotz, who himself arrived only ten minutes earlier on his motor scooter. The police then escorted Diallo to a private room. It is not clear when they began to question her or officially took control of the case. According to the prosecutor’s bill of particulars, members of the hotel security staff had remained in contact with Diallo for at least another twenty-five minutes, since it states that at 2:30 p.m. “a photograph of the defendant was shown to the witness [i.e. Diallo] by hotel security without police involvement.” If so, even after leaving the bench (and video surveillance) and going into a room with the police, she remained available to the Sofitel staff. (I asked both Deputy Commissioner Paul Browne and Deputy Inspector Kim Royster why, according to the bill of particulars, the police were not officially involved at this point, but they declined to comment.) Nor was the presidential suite entered by the police, according to the records, until 2:52 p.m., which was five minutes after Sheehan, the Accor safety director, arrived at the hotel. It was not until 3:28 p.m. that the police took Diallo to the hospital, and that she was finally medically examined and then formally interviewed by police detectives.

The account she provided was of a brutal and sustained sexual attack. She described how her attacker locked the suite door, dragged her into the bedroom, and then dragged her down the inner corridor to a spot close to the bathroom door—a distance of about forty feet—and, after attempting to assault her both anally and vaginally, also forced her twice to perform fellatio.

After that, she said she fled the suite and hid in the far end of hallway until he left. She later identified DSK in the lineup as her attacker.

Based on her description, the police crime-scene unit sealed off two crime scenes—the presidential suite and the far end of hallway—and located five areas of the carpet in the interior hallway leading to the bathroom of the presidential suite that potentially had stains of semen or saliva. The next day, May 15, police detectives brought sections of the carpet from the hallway, as well as the wallpaper, to the police forensic

biology lab. A preliminary examination showed that one of the five stains in the carpet, located about six feet from where Diallo had said she was assaulted, contained a mixture of semen and amylase (an enzyme from saliva) that was consistent with the DNA of DSK and Diallo. This was direct evidence that they had engaged in fellatio, as Diallo had claimed. (Three of the other stains also tested positive for semen, as did the wallpaper, and a fourth stain showed a mixture of semen and saliva, but these stains were determined to be from six other individuals, and their sexual activity was assumed to be unrelated to the incident under investigation.)

The next issue was whether force had been used. To this end, DSK was examined at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital for any telltale bruises, traces of her DNA under his fingernails, or any other evidence of a struggle. None was found. Then, on Sunday, May 15, DSK was formally arrested.

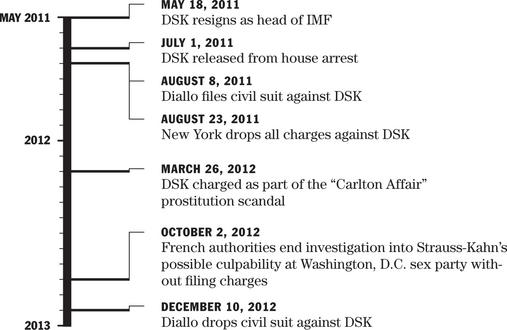

The Manhattan district attorney office, under DA Cyrus Vance, Jr., was possibly the best staffed prosecution team in the United States. Its trial division alone had more than fifty assistant district attorneys, as well as dozens of investigative analysts and paralegals. Its sex-crimes unit, which had been assigned the case, had been the subject of a laudatory HBO documentary. Immediately after DSK’s arrest, Lisa Friel, who had headed the sex-crimes unit, began examining the case, as did John “Artie” McConnell, the prosecutor assigned to the case; Ann Prunty, his “second” chair; and Joan Illuzzi-Orbon, the assistant DA who headed the newly created hate crimes unit. The first issue facing this formidable team of prosecutors was bail.

Bail is not unusual in the case of a first-time offender with no previous criminal background who is employed. DSK was the managing director of the IMF. His lawyers, William W. Taylor, III, and Benjamin Brafman, immediately moved to arrange bail. According to DSK’s lawyers’ understanding of their conversation with the prosecutors, a deal was arranged at 4:00

p.m. on May 15 whereby the prosecution would recommend $250,000 cash bail and DSK would relinquish his passport. But at 8:00 p.m. that Sunday, Lisa Friel told Brafman on the phone that “things had changed and there was no more agreement.” Instead, the DA would recommend that bail not be granted. (Friel herself left the case shortly afterward and resigned from the district attorney’s office.)

What had reportedly happened in the four-hour interim was that Vance had received information from Paris bearing on the case. Although it had been initially reported that this phone call concerned a Frenchwoman, Tristane Banon, who had charged that DSK had attacked her, that accusation had not even been officially filed on May 15 (and it was subsequently dismissed).

Instead, an investigation in the French newspaper

Libération

by Fabrice Rousselot found that the call came from the phone of a senior official in the French government. The official, according to Rousselot’s investigation, said that DSK was implicated in a prostitution case that involved, among other things, transporting prostitutes to Washington, D.C. If it turned out to be true that DSK might be involved in a Washington prostitute ring, releasing him on bail could embarrass the DA’s office, especially if he fled.

There may have been more than one phone call from Paris. At the bail hearing the next day, according to the court transcript, McConnell requested that Judge Melissa Jackson hold DSK without bail, explaining in an apparent reference to the communications with Paris that “we are obtaining additional information on a daily basis regarding his behavior and background.” He continued, “Some of this information includes reports he has in fact engaged in a conduct similar to the conduct alleged in the complaint.” He added that these reports were as yet unverified, but he did not specify who was supplying his office with these reports “on a daily basis” less than two days after DSK’s arrest. But if the reports concerned DSK’s sexual

activities at the W Hotel in Washington earlier that week, where he had attended a sex party on May 13, this raises the question of how the French government, or whoever was supplying the reports, had obtained such up-to-date intelligence on DSK’s private activities in Washington.

For their part, the prosecutors now strongly deny that this information from France was the decisive factor in their opposing bail. Their principal concern, according to a source in the prosecutor’s office, was that DSK, if released on bail, might use his connections to flee to France. Whatever shaped the decision, Judge Jackson acquiesced and denied DSK bail.

The prosecutor’s opposing bail had two immediate consequences. First, DSK was imprisoned on Rikers Island for four days (after which another judge granted bail). Second, it started a relatively brief clock for the prosecutors. New York state law required the prosecution to gather evidence and present it to the grand jury within 144 hours. This rush resulted in a presentation before all the facts could be assembled. For example, within that period, the prosecutors had not yet obtained electronic key-swipe records. When they did the following month, those records cast a very different light on the case.

The reasons that the prosecutors may have been willing to risk this rush to judgment is, as the district attorney publicly stated, that it was assumed that there was a solid case against DSK. After all, preliminary DNA evidence established that DSK had a sexual encounter with Diallo. The semen stains, moreover, placed it in the presidential suite in the area that she described to the police. Neither DSK nor his lawyers had denied that it had occurred. Instead, they said that it was not forced. So the only legal issue was whether or not it was consensual. That would be up to a jury to decide. And as is common in sex-crime prosecutions, the verdict would depend heavily on the credibility of the prosecution’s only real witness. If the jurors believed Diallo beyond a reasonable doubt that force was used,

DSK would be convicted. And, as far as her creditability went, the prosecutors believed that they were on solid ground. The initial police investigation had turned up no “red flags” in Diallo’s background. She had, for example, never been arrested or accused of a crime. Although she had entered the United States under an alias (as do many refugees), she had been granted political asylum by the U.S. Immigration Court. Diallo had worked for the Sofitel for three years without any reported problems and was described by her supervisor as a “model employee.” And while she was the only witness to the attack itself, two other hotel employees—the room-service waiter and the head housekeeper—had given police statements that supported her story (although, as it later turned out, these witnesses had the opportunity to hear Diallo tell her story in the security area before the police were called in).

When the prosecutors went to court on May 15 and argued against bail, they assumed they had a credible witness.

Diallo also impressed them subsequently with the vivid account she gave of experiencing a previous rape by soldiers in Guinea. She had been so convincing that she brought tears to the eyes of one of the prosecutors. After hearing the testimony of Diallo, the grand jury indicted DSK on May 18. It charged him with two counts of criminal sexual acts, one count of attempted rape, two counts of sexual abuse, one count of unlawful imprisonment, and one count of forcible touching.