The Annals of Unsolved Crime (24 page)

Read The Annals of Unsolved Crime Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

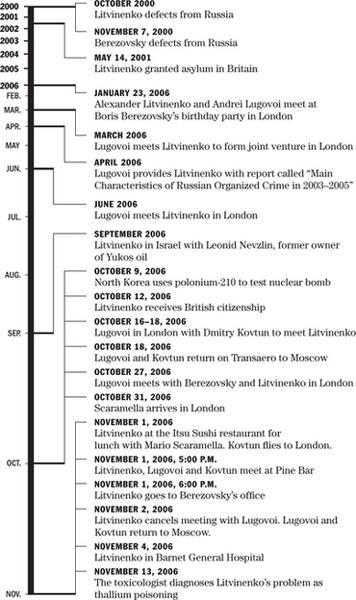

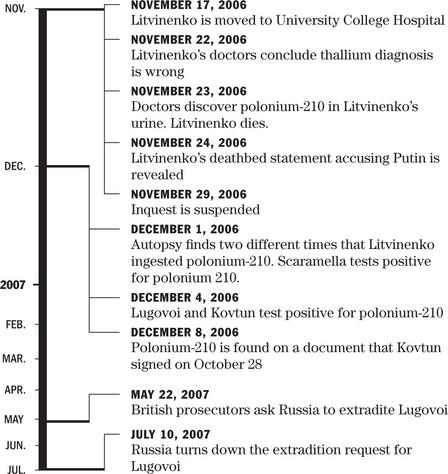

The mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of Litvinenko from radiation poisoning spawned a different kind of international crisis. British authorities told the press, “We are one-hundred percent sure who administered the poison, where and how,” but they refused to disclose their evidence. Nonetheless, the consensus that the Russian secret service was behind the poisoning was so powerful that a

Washington Post

editorial could assert that the poison “dose was almost certainly carried by one or both of the former Russian security operatives—one of them also a KGB alumnus—whom Litvinenko met at a London hotel November 1.” The KGB alumnus was a forty-two-year-old Russian security expert, Anatoli Lugovoi. Like Litvinenko, Lugovoi had been exposed to polonium-210, and after Litvinenko’s death he was hospitalized. Based mainly on the fact that Lugovoi had been in contact with Litvinenko shortly before his death, and contaminated by polonium-210, Great Britain demanded that Russia extradite him, so he could be tried for the murder of Litvinenko. When Russia refused, Great Britain expelled four Russian diplomats from London, in reprisals reminiscent of the Cold War.

To find out what had brought Lugovoi in contact with Litvinenko, I went to Moscow to see him in May 2008. There was no doubt that he had been with Litvinenko in London. On November 1, 2006, witnesses saw Lugovoi with Litvinenko in the Pine Bar of the Millennium Hotel, where Lugovoi was staying with his family. A waiter recalled bringing Litvinenko tea. This was less than a day before Litvinenko became ill. Subsequently,

the Pine Bar as well as Lugovoi’s room tested positive for polonium-210, leading to an early theory that Litvinenko had been poisoned in the Pine Bar. But then it turned out that Litvinenko had had a sushi lunch at the Itsu restaurant some four hours earlier, and that restaurant, as well as Litvinenko’s lunch partner, Mario Scaramella, tested positive for polonium-210. This suggested that Litvinenko had been contaminated prior to his tea at the Pine Bar. Lugovoi had also had a number of earlier meetings with Litvinenko, including one on October 16, 2006, at a lap-dancing club called Hey Jo. The owner, David West, and others recalled seeing both men seated in a VIP booth. The booth then tested positive for polonium-210, as did the seat Lugovoi had occupied on the British Airways flight back to Moscow on October 19. If so, both men were exposed to polonium-210 over a month before Litvinenko died. But how?

When I met Lugovoi in his office in Moscow, he had just been elected to the Duma, the Russian parliament, which gave him immunity, and with that protection he talked freely about his relationship with Litvinenko. He told me that they both had been intelligence officers in the KGB and FSB in the 1990s, but that then he had become a supporter of Putin, while Litvinenko had done everything he could to discredit Putin, and then defected to London. I asked how they came together a decade later. Lugovoi answered in a single word: “Berezovsky.”

He was referring to Boris Abramovich Berezovsky, a billionaire living in London, who had been the single most powerful oligarch in Russia in the 1990s. He not only controlled whole sectors of the Russian economy and the country’s largest television channel, but he was part of the government apparatus, serving as the deputy secretary of its National Security Council. Both he and Litvinenko acted as Berezovsky’s protectors in the FSB. Litvinenko was deputy head of its organized-crime unit, while Lugovoi was in the Ninth Directorate, which was responsible for guarding top Kremlin officials, including

Berezovsky. He said that Berezovsky was so impressed with his work that he hired him as head of security at the television channel, ORT, which Berezovsky co-owned. With an enigmatic smile, Lugovoi said that both Litvinenko and he had performed extraordinary services for Berezovsky. With a gun in one hand and his FSB credentials in the other, Litvinenko had prevented Moscow police from arresting Berezovsky on a murder charge. He then ended his own career in the FSB by exposing an FSB faction’s alleged plan to assassinate Berezovsky. As a consequence, Litvinenko was imprisoned. For his part, Lugovoi helped Berezovsky’s partner break out of a Moscow prison—an act for which he also served prison time. Meanwhile, Berezovsky moved to London and became Putin’s arch-foe. In November 2000, he helped Litvinenko escape to England, where he financially supported him and sponsored his investigations for the next six years.

I asked how Berezovsky had repaid him. Lugovoi answered with a wry smile: “By bringing me to Litvinenko.”

The reunion came in January 2006 in London. Berezovsky had rented Blenheim Palace—the birthplace of Winston Churchill—to give himself a lavish sixtieth birthday party. There were some 300 guests in formal attire and, in the center of the room, a giant ice sculpture representing St. Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square, covered with Caspian caviar. Berezovsky’s seating plan placed Lugovoi at a small table with three men: on his right was Litvinenko, who was now engaged in conducting investigations into Russian atrocities in Chechnya. Across from him was Akhmed Zakayev, the exiled leader of the Chechen resistance who headed the Committee on Russian War Crimes in Chechnya. On his left was Alexander Goldfarb, who ran Berezovsky’s foundation, which helped support both Litvinenko’s and Zakayev’s activities.

As it turned out, the people at his table that night would be among the last to see Litvinenko alive ten months later. Lugovoi

saw him in the Pine Bar at 5:00 p.m. on November 1. Zakayev then picked up Litvinenko at the Pine Bar and drove him to Berezovsky’s office. Goldfarb later wrote Litvinenko’s dramatic deathbed statement. But that evening, as Lugovoi recalls it, there was nothing but good cheer and celebratory toasts.

Soon afterward, Lugovoi explained, Litvinenko called him with a “business proposal.” They would form a joint venture, backed by Berezovsky, to gather information in Moscow. The idea, according to Lugovoi, was to use his connections in Moscow to get “business data” that Litvinenko could sell to London clients, including, as it turned out, the former owners of Yukos, the largest oil enterprise in Russia. Yukos was no ordinary oil company: with tens of billions of dollars stashed away in accounts in Cyprus, Gibraltar, and other offshore havens, it had become by the early 2000s a virtual counter-state to the government. In the battle that ensued between Yukos and Putin, Yukos was charged with tax fraud and, through enormous fines, its assets in Russia were effectively expropriated.

Since this “joint venture” would involve Lugovoi in a collaboration with some of President Putin’s most determined enemies abroad, including Litvinenko, Berezovsky, and the former owners of Yukos—all of whom Russia was then attempting to extradite from Great Britain and Israel—I asked Lugovoi if he had been concerned that this engagement could cause him problems with the authorities in Moscow. He answered, “I had no such worries.” Did this mean that he had informed Russian authorities about his participation in this venture, I asked. He shrugged, and said, “I am now a member of the Duma. What does that tell you?”

As this project developed, much of the “business data” requested from Lugovoi concerned individuals connected in one way or another with Yukos. The two principal owners of its holding company were Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who was imprisoned in Siberia, and Leonid Nevzlin, who had fled to Israel.

In Tel Aviv, Nevzlin had set up a private intelligence company, ISC Global, with divisions in London and Tel Aviv, to gather information that would help him fight Russian efforts to get control of the offshore accounts. It was in its London office, renamed RISC Management, Ltd., that Lugovoi said he next met with Litvinenko. According to Lugovoi, RISC asked him to obtain in Moscow relatively innocuous reports, such as one entitled, “Main characteristics of Russian Organized Crime in 2003–2005.” He acquired the report from former FSB officers, and delivered it to Litvinenko, who paid him. Litvinenko then gave him a list of other data to acquire for RISC, including government files on Russian tax officials. Litvinenko threatened that if he did not get this material, Lugovoi might have a “problem” renewing his British visa, and his visa was indeed held up. When he then agreed to get this sensitive data, not only was his visa renewed, but $8,000 was wired to his bank account. This joint venture now had all the earmarks of a classic espionage operation. Lugovoi was compromised, threatened, and paid to deliver intelligence. This incident made him suspicious that Litvinenko, aside from working for Berezovsky, was involved with British intelligence. “How else could he get my visa withdrawn—and reinstated?” he asked rhetorically. (Four years after my meeting with him, Lugovoi’s suspicions were confirmed when on December 13, 2012, in a preliminary hearing for an inquest in London, it was disclosed that Litvinenko was indeed on the payroll of the British intelligence services at the time of his death in 2006.)

The game took a further turn in September 2006, when Litvinenko made a trip to Tel Aviv to personally deliver to former Yukos holding-company owner Nevzlin what he called the “the Yukos file.” According to Lugovoi, it contained much of the information that he had provided. Nevzlin admits receiving the dossier from Litvinenko, although he insists it was unsolicited. In any case, after Litvinenko returned from Israel, Lugovoi says

he found him increasingly on edge. About a month later, on October 27, Lugovoi was summoned to London by Berezovsky. A few hours after he arrived, he recalled that Litvinenko turned up at his hotel. Litvinenko said he needed to retrieve the cell phone that Lugovoi had been given to use for RISC business. After Lugovoi gave it to him, Litvinenko removed the SIM card, which contained a digital trail of his contacts. Litvinenko then told him that the next meeting with RISC would be on November 2.

Lugovoi said that the last time he saw Litvinenko was at 5:00 p.m. on November 1 at the Pine Bar. Litvinenko had come to discuss their planned meeting the next day at RISC, and, as Lugovoi was on his way to a soccer match, he stayed only briefly. The next day, Litvinenko called to say he was sick and canceled the meeting. So Lugovoi returned to Moscow.

When I asked Lugovoi who was providing the expenses for his trips to London, he said Litvinenko gave the money to him in cash but he assumed it came from Berezovsky. Not only had the exiled billionaire been financing Litvinenko ever since he had defected to London, but he owned the house in which Litvinenko lived and the office that he used. He had also come to one of the meetings at RISC, and he frequently called Litvinenko on the cell phone reserved for RISC activities. So, even though Litvinenko did not say so, Lugovoi had little doubt that Berezovsky was behind their venture.

Had he kept the FSB informed about his meetings with Litvinenko, Berezovsky, and RISC officials? I asked. “I did what was necessary,” Lugovoi replied, smiling knowingly.

He insisted that he had no knowledge about how Litvinenko, or he himself, got contaminated with polonium-210. Subsequently, he provided the same answer on a polygraph examination, and, according to the examiner, showed no signs of deception.

I next went to see Dmitry Kovtun, who had accompanied

Lugovoi to London for the last two meetings with Litvinenko. Like Lugovoi, Kovtun had been contaminated with polonium-210. Since his seat on the Transaero plane on which he had arrived in London on the morning of October 16 showed no trace of polonium-210, but his flight out of London tested positive for it, he had most likely been contaminated in London. But how?

I met him at the Porto Atrium, an expansive restaurant on the Leninsky Prospect known for its extensive wine cellar. A compact man in his mid-forties with greying hair, Kovtun explained how he got, as he put it, “into this mess.” He had just returned from Germany, where he had served in a Soviet Army intelligence unit and married, then separated from, a German woman. He was looking for international business contacts, and Lugovoi had proposed he go to London with him. When they arrived, they were met by Litvinenko, who spent most of his next two days with them. Kovtun’s next encounter with Litvinenko came two weeks later, when Lugovoi invited him to come to London for a major soccer match, for which Berezovsky was providing tickets. When he arrived on November 1, he joined Lugovoi and Litvinenko for a pregame drink at the Pine Bar.