The Ancient Alien Question (28 page)

Read The Ancient Alien Question Online

Authors: Philip Coppens

Unfortunately, as the discovery and announcement of the artifact was made during the Cold War, Western science as a whole is largely unaware of it, and uninterested in it. In the eyes of the

people who studied the object it is a candidate for best evidence, but it is definitely not the best-known evidence.

One famous example of an oop-art is the so-called Baghdad Battery. It was found in 1936, when the Directorate General of Antiquities carried out excavations in the mounds east of Baghdad, known as Khuit Rabboua. The finds date back to the Parthenian Period (227–126

BC

), though the excavations were not well recorded and the style of the pottery is actually Sassanid, which is

AD

224–640.

The finds included a pottery jar that measured 5 inches and contained a copper cylinder with an iron bar fixed in its center that extended a little out of its opening. The cylinder was covered by a layer of bitumen (tar) and its copper base was also covered with bitumen, as was the jar itself.

In 1940, Wilhelm König, the German director of the National Museum of Iraq, published a paper speculating that the objects might have been galvanic cells, perhaps used for electroplating gold onto silver objects. If he’s correct, the Baghdad Battery would predate Alessandro Volta’s 1800 invention of the electrochemical cell by more than a millennium. In 1973, the battery was displayed in the Baghdad Museum and was regarded as the oldest kind of dry battery ever discovered. Around that time, German Egyptologist Arne Eggebrecht built a replica of the battery and filled it with freshly pressed grape juice. He generated 0.87 volt of current, which he then used to electroplate a silver statuette with gold.

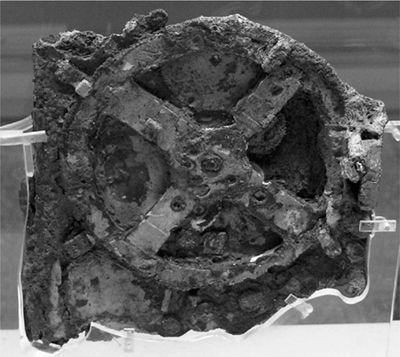

Another oop-art is the Antikythera Device. In 1900, a Greek sponge diver named Elias Stadiatos, working off the small Greek island of Antikythera, found the remains of a Greek ship at the bottom of the sea. In early 1902, Valerio Stais was sorting through the recovered material, all donated to the Museum of Athens, when he noticed a calcified lump of bronze that did not fit anywhere, and that looked like a big watch. He guessed it was an astronomical clock and wrote a paper on the artifact. But when it was published, he was ridiculed for even daring to suggest such a thing. His critics argued that sundials were used to tell time. A Greek dial mechanism was unknown to the archaeological community, even though it was described on what must therefore have been a purely theoretical basis. The status quo was that “many of the Greek scientific devices known to us from written descriptions show much mathematical ingenuity, but in all cases the purely mechanical part of the design seems relatively crude. Gearing was clearly known to the Greeks, but it was used only in relatively simple applications.”

2

And therefore, because scientific dogma had said so, the Antikythera Device could not be. It was physical evidence, but deemed to be impossible, and therefore ridiculed and debated away.

The Antikythera Device was found in 1900 in a shipwreck. It was 50 years before anyone realized the device was a mechanism that incorporated accurate workings for various bodies of our solar system. It is now often considered to be the first computer. © Marsyas via Wikipedia.

In 1958, Yale science historian Derek J. de Solla Price stumbled upon the object and decided to make it the subject of a scientific study, which was published the following year in

Scientific American

. This marked the revival of interest in the Antikythera Device, more than half a century after its discovery. Part of the problem, Price felt, was the device’s uniqueness. He stated: “Nothing like this instrument is preserved elsewhere. Nothing comparable to it is known from any ancient scientific text or literary allusion. On the contrary, from all that we know of science and technology in the Hellenistic Age we should have felt that such a device could not exist.”

3

He likened the discovery to finding a jet plane in Tutankhamen’s tomb, and at first believed the machine was made in 1575—a first-century

BC

creation date remained hard to accept, let alone defend.

Ever since, the Antikythera Device has been subjected to some of the most innovative scientific studies. They have shown that the Greeks were extremely advanced when it came to applying their astronomical knowledge. Today, the Antikythera Device is worshipped by many as the first calculator—the first computer. Price labeled it “In a way, the venerable progenitor of all our present plethora of scientific hardware.”

4

It took more than a century from the discovery of the Antikythera Device until we had some understanding of its technical complexity, as well as a general consensus that it is indeed a highly technical artifact. Part of the problem was that the find was unique; if ET in fact only gave us one present, then it appears it’s not good enough proof.

Palenque’s Ancient Astronaut Slab

The lid of Lord Pacal’s tomb in Palenque is among the most often quoted evidence for the Ancient Alien Theory. The discovery of this tomb occurred once Alberto Ruz Lhuillier was appointed director of archaeological exploration of the Mayan ruins of Palenque in 1949. Though the site had been known since 1750, it was only in 1925 that the first archaeological work was carried out. Ruz Lhuillier began by clearing the ruins of earth and rubble, and in 1952 he penetrated deep inside the so-called Temple of Inscriptions, where he discovered a sarcophagus belonging to Hanab-Pacal, the ruler of Palenque, who died in

AD

683 at the age of 80, after an impressive 68-year reign.

It was highly unusual to find an intact tomb, and it was a minor miracle that when Ruz Lhuillier lifted up the lid of the coffin, it did not break. Inside was a mummy, its head covered by a mask made up of 200 pieces of jade. Very quickly one magazine ran a story on the “Palenque giant,” claiming Lord Pacal was 12 feet tall. In reality, he was 5.9 feet, which was still remarkably taller than the average height of his subjects.

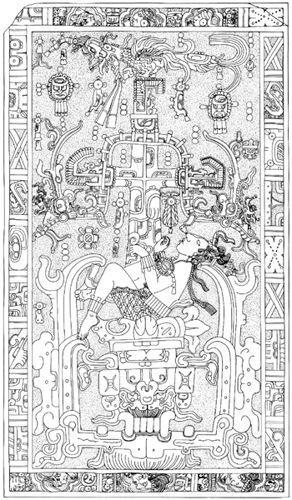

If Pacal had been a giant, that would have received widespread interest, but instead, it was the slab of the sarcophagus, which weighs 4.5 tons, that took the limelight, as it depicted one of the most intricate and baffling reliefs found anywhere in the world. The carvings are about 1 inch deep and depict a human being in an unusual pose. That’s about the only thing everyone agrees on. The first explanation offered was that this was a Native American on a sacrificial altar, about to have his heart ceremonially removed. Ancient astronaut proponents thought differently: In

Chariots of the Gods?

von Däniken compared the pose to that of the 1960s Project Mercury astronauts. The relief has since attracted decades of intense speculation by other Ancient Alien enthusiasts, who believe that the relief should be turned 90 degrees, at which angle it depicts Lord Pacal riding a technical device resembling a low-flying scooter. Engineer Laszlo Toth has done a series of technical drawings that detail the workings of the machine on which Pacal supposedly rides. He claims to have identified a mask on Pacal’s nose, his hands manipulating controls, the heel of his left foot on a pedal, and a little flame issuing from the machine’s exhaust.

The Pacal tomb is one of the best-known billboards for the traditional Ancient Alien Theory. When flipped 90 degrees, it appears as if Pacal is riding a type of flying scooter. Only when confronted with this challenge did archaeologists finally begin to look more carefully into the potential meaning of this tomb slab. © Madman2001 via Wikipedia.

Archaeologists strongly disagree. To their credit, they no longer argue that the image is of a brutal human sacrifice, but instead interpret the lid depicting Pacal descending into Xibalba, the Mayan Underworld. They support their conclusion by showing that below Pacal is the Mayan water lord, the guardian of the underworld, and the “device” is in fact the world tree. As he falls, he travels down the tree, which was identified with the Milky Way, or

Sak Beh

. Along the edge of the sarcophagus are a series of inscriptions, which lists the death sequence of the eight generations of kings before Pacal. One of the best detailed explanations of the lid is offered by Linda Schele and Peter Mathews, who in

The Code of Kings

conclude that “Pacal falls in death, but his very position also signals birth—his birth into the Otherworld.”

There are numerous other examples of this imagery depicted on various Mayan sculptures, some dating to the Olmec period. The difference between Pacal’s tomb and the other depictions is that Pacal’s rendition of this descent is highly stylized, and the end result, when tilted 90 degrees, is indeed suggestive of a space-bike-riding king. Given that this image is on Pacal’s tomb, depictions of the Underworld and the world tree are definitely more apt than a vehicle.

Pacal’s tomb is evidence that treating objects in isolation can sometimes mean that the answer is no. As with the Nazca lines, though, posing the Ancient Alien Question did mean that science was pushed to come up with the correct answer.

One of the dangers of any theory, of course, is interpretation. For example, the statues at Tula, in Mexico, have enigmatic ears—largely rectangular, which some Ancient Alien theorists

have proposed could be interpreted as hearing protection. A more logical explanation is that the ears are either overly stylized or protected by a rectangular part of a headdress. Though the statue indeed holds an object in its right hand that

could

be interpreted as a type of laser, it could just as well be a wooden or metal object. What it is—or should be—is largely determined by the perspective of the observer. And when one has only a simple depiction for evidence, that depiction, or any analysis of it, will never be proof of an alien presence.

The Goldflyer

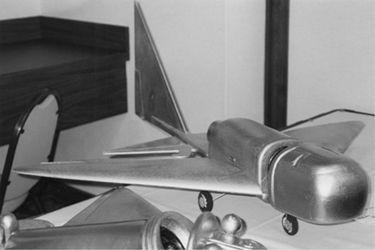

Looking at the archaeological record and finding anomalies is precisely how major advances in the alien debate have progressed. In

Chariots of the Gods

, Erich von Däniken remarked that, in his opinion, a particular artifact recovered from Colombia was nothing short of a prehistoric airplane. His statement was controversial, as archaeologists had catalogued the small artifact as an insect. The artifact in question is currently on display in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Its explanation states: “Gold artifact, a stylized insect, from the Quimbaya culture, Antioquia province, Colombia, ca. 1000–1500

AD

.” At one point, replicas of the piece could be bought from the Smithsonian gift shop.

There are a number of other such “insects,” five in the collection of the Gold Museum at the Bank of the Republic in Bogota. The “Bogota aircraft” was first publicized by Ivan T. Sanderson, who thought the artifact represented a high-speed aircraft. He sought the opinion of a number of aircraft engineers, who supported his idea. Another stylized “goldflyer” is in the possession of the Museum of Primitive Art in New York City, where it is identified as a “winged crocodile.” Dr. Stuart W. Greenwood has tracked down 18 of these artifacts in museums and private collections, but in all instances, archaeological officialdom labeled them insects or something similar.

Other books

Pioneer Passion by Therese Kramer

Penelope Goes to Portsmouth by M. C. Beaton

The Trail Back by Ashley Malkin

Out of Control by Shannon McKenna

Prince of Spies by Bianca D'Arc

His Deepest Desire (BBW Domination Billionaire Erotica) by Beatrix, Simone

Forbidden: The Sheikh's Virgin by Trish Morey

Colour Series Box Set by Ashleigh Giannoccaro

Cold Allies by Patricia Anthony

1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created by Charles C. Mann