The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (2 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

O

NE OF THE GREAT CULTURAL CONTRIBUTIONS

of Spain to the world is the

carmen

. Now a true carmen is an enclosed patio garden on the hill of the Albaicín in Granada, and to qualify for the name it must have a view of the Alhambra and the peaks of the Sierra Nevada beyond. Apart from that, a number of essential elements can be deployed more or less at random: these include grapevines, tall slender cypresses, orange and lemon trees, a persimmon or two, perhaps a pomegranate, and myrtle – whose scent was believed by the Moors to embody the very essence of love.

The surface of a carmen should be cobbled in the style known as

el

empedrado Granadino

– a grey and white pattern, again devised by the Moors, using the river stones that occur in abundance throughout the province. There should also be a fountain and a pool and preferably a number of runnels

and rills leading the water hither and thither in a fashion perfectly conceived to make you feel cool and contemplative on a hot summer’s day. If the thing has been done right, the interplay between light and shade, the mingling scents of the flowers and the chuckling of the water in its channels will induce a profound contentment and sense of peace as you wander the cobbled paths, perhaps hand in hand with a good friend, musing playfully, the pair of you, upon the mysteries of the universe.

If you are really fortunate, a nightingale will come and nest in your cypress tree and then the pleasure becomes sublime. But that can’t be counted on, so most

carmen

owners make do with a canary in a cage. I personally rather like the sound of caged canaries – it is one of the essentials of a Spanish street – but it hardly compares to the

nightingales

and, besides, the song of the caged bird should be more a source of distress than pleasure to sensitive, modern man.

Halfway up the Cuesta del Chápiz, between Sacromonte and the Albaicín, is the Carmen de la Victoria. Owned by the university, it is one of the prettiest

carmenes

in the city. I pushed open the gate and stood for a minute adjusting to the deep shade after the brightness of the street with its glaring white walls. I was passing through the city on the way home from a trip to Málaga, and had come here partly to visit the

carmen

– but mainly to see my friend Michael.

Michael Jacobs is an art historian, a writer, a traveller and a scholar and a formidable cook, as well as being one of the most entertaining people I know. Somewhere within the confines of the

carmen

he was holding court to a group of English tourists who had paid good money to be guided around the cultural monuments of Andalucía. Michael had

doubtless dazzled them that morning with his erudition and somewhat unorthodox views on the Alhambra: he likes to point out that, given how much of the Moorish palace was rebuilt after a fire at the end of the nineteenth century, it is about as authentic as the Alhambra Palace Hotel down the hill. Now there would be a slack period while they wandered among the delights of the

carmen

, sinking a drink or two before lunch.

I came upon Michael pacing to and fro along a rose arbour, talking agitatedly on his mobile phone. He was gesticulating wildly and occasionally clapping his free hand to his head. Some catastrophe was clearly assailing him, as it tends to do, for he is a person who hovers happily on the very verge of chaos. An ordinary mortal’s carefully laid plans, meticulous organisation and unsurprising results would be hell for him – even if he were able to aspire to such a mode of existence.

I waited, sat on a bench and watched as two tiny white butterflies wove in and out of a trellis of dusty pink roses. At last Michael was finished. We embraced in a sort of manly Mediterranean bear hug – a gesture by which we seek to confound the stiffness of our Anglo-Saxon

upbringings

. ‘Ah yes, Chris… That’s w-wonderful… Just the man… It’s good you’re here, actually, because… W-would you like a beer, yes you must have a beer…’

We moved to the bar where I ordered a wine; I’ve never much liked Spanish beer. ‘Well, actually,’ resumed Michael, ‘what I was thinking w-was… have you ever been on one of those… it’s just that… I know there are people who… w-why don’t you?’ He was saved from having to commit himself to anything more substantial by the

ringing

of his phone. ‘Excuse me, Chris’ – he looked at the

screen – ‘Ah, it’s Jeremy again. Ah… H-hallo, Jeremy… Yes Jeremy…’ There followed a conversation if possible even more inconclusive than the one I had just been involved in.

Michael has the energy, proportionate to his size, of an insect, and races about at great speed on unpredictable courses full of hesitations and volte-faces, but somehow manages to achieve a great deal, in much the same way, I suppose, as the insect does. He has published, I think, twenty-six books, and never more than three, he says happily, with the same publisher. And all these books are the sort of books for which you need to do immense quantities of research and have reams of arcane

knowledge

at your disposal. He forever has some new project on the boil. As well as his copious output he has the most terrifying capacity for drinking and socialising that I have ever encountered. He will stay out carousing in bars and knocking back gargantuan quantities of wine until four or five in the morning and then wake at seven to hurl himself into the next day with not the faintest trace of a hang-over. One imagines that an organism that receives such constant and merciless battering would soon fall to bits, but no – at fifty, Michael is as vital and lively as ever.

‘Ah yes… Chris, I’ve got a bit of a problem with this group… or not so much this group as another one. You see I’m… erm… double-booked… well, not exactly

double-booked

but I was supposed to stay available in case the

itinerary

changed and it… erm… has, and I’m… erm… not…’ He looked decidedly sheepish. ‘I’m booked in to lecture to a whole load of college students instead. Jeremy’s having a nervous breakdown over it.’

‘Who’s Jeremy?’

‘Ah, Jeremy… you’d like Jeremy… Well, actually he’s quite a strange sort of person… Very… erm… organised.’

‘Yes, but who is he?’

‘Ah yes, well, Jeremy runs these tours for well-heeled Americans…’

‘Oh, I see now,’ I said, although in fact I didn’t.

‘As a matter of fact…’ said Michael, studying me with an odd intensity. ‘Yes, you could be. I mean, w-why not…?’ I returned the stare, as the meaning of Michael’s look and meandering words began to dawn on me. It was maybe a not very striking coincidence that we both happened to be wearing black jeans, white collarless shirts and black leather jackets that had seen better days. But the

resemblance

went beyond that. We both wore round glasses, both had thinning curly grey hair and rather rubicund

complexions

, and although Michael loomed half a head taller, we were of similar build.

Michael was by now smiling complacently, with the look of one who has resolved a mathematical conundrum. ‘You d-don’t by any chance fancy spending a few days in Seville do you, Chris?’ he asked, in a tone that seemed deliberately casual.

‘You mean, impersonating you – and taking round one of your groups?!’

‘Er… yes, that’s more or less what I had in mind.’

‘They’d rumble us. I mean I may look a bit like you and even dress a bit like you, but I know bugger all about art!’

‘Oh, that doesn’t matter a bit. I’ve got some books you can borrow right here in my bag and you’ve got all of the ones I’ve written on Andalucía. And there’s some pamphlets about the group, too – they’re inside the b-books.’

Michael’s head almost completely disappeared into an ancient, scuffed leather briefcase. He emerged clutching a couple of books, and a few nondescript twigs which he stared at in amazement and then tossed aside. ‘You’ll be fine,’ he assured me, handing over the haul. ‘You’re used to giving talks and you read Spanish, don’t you? So at the worst you can just translate the gallery’s captions.’

There’s something immensely encouraging about Michael, which makes a madcap scheme, coupled with the offer of an all-perks-included midweek break in Seville, seem oddly attractive. ‘Okay,’ I said. ‘I’m on.’

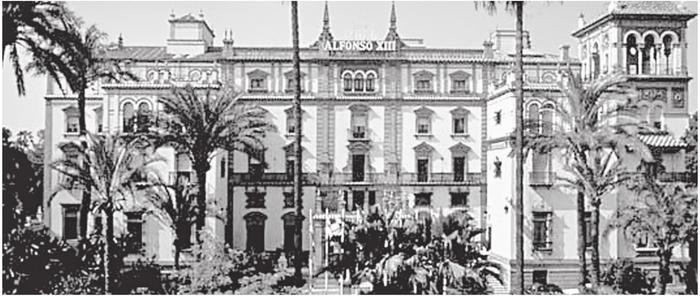

‘Well, of course you are,’ he clapped me on the shoulder. ‘That’s w-wonderful. They’ll be meeting me… um… you in the foyer at the Hotel Alfonso XIII at 10am on Monday and the first trip’s to…’ He rummaged among the papers. ‘Ah yes, the Giralda, quite exquisite and easy to explain. You just turn up and talk about the Moors. I’ll square it all with Jeremy, who’ll go with you.’

And so it was that I found myself launched on a new career path, as lecturer on Andalucían art and architecture, shepherd to wealthy American art lovers, and Michael Jacobs impersonator. I strolled down the hill to the city and turned in at the doorway of the Librería Urbana to pick up the tools of my new trade.

A slight feeling of nausea crept over me there, confronted by a shelf full of art history books, but I forced myself to get a grip and limit the search to the buildings we would be visiting in Seville. I would bone up on each subject the night before – a tried and tested measure that had got me through school (though admittedly not through any actual exams). Still, I had a whole four days ahead of me to get up to speed. It would be fine. These wealthy Americans

were bound to have more money than erudition. And thus I comforted myself as I drove out of Granada towards the provincial town of Órgiva and the remote patch of mountainside that I call home.

‘Who are these people, then, Chris?’ asked my wife Ana, leaning over my shoulder as I pored over the brochures that had spilled from Michael’s book. Porca, our

parakeet

and Ana’s familiar, seemed to echo the question in squawks from a new perch he’d made on the top of my art history pile.

‘Um, well, they’re all Americans and…’ I scanned the printed sheet again as if unwilling to take in the import of the words. ‘Well, it seems that they’re the Trustees of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Hell’s teeth! And they’re not just ordinary trustees either… They’re a sort of elite – they all cared enough about fine art to donate over a million dollars to the museum, which is what seems to have

qualified

them for a place on this jaunt.’

Ana fixed me with one of her steady looks. ‘You can’t do it, Chris. It won’t work. You’ll just have to phone Michael and tell him it’s impossible. You could offer to help out a bit, but you surely can’t go through with this stunt!’

She was right, of course. I needed to talk to Michael, and soon. But then again, I hate to let a friend down and I really do believe that most things will work out in the end if you sit back and let them. So I put the phone call off, got on with other chores and leafed casually through the odd art book while waiting for the kettle to boil or for Chloë to get ready for school. And before I knew it Sunday night

had hurtled along, leaving me with no other choice but to do some last minute homework and present myself to the good Bostonians.

Now, I pride myself that I can absorb books as well as the next literate being. But I am constitutionally unable to swot. As soon as I have to glean information for any real purpose, my eyes glaze over or rake the room for a

distraction

, and before I know it I’m either asleep with my head on the book cover or replacing the strings on my guitar and tuning them up. That night it was sleep that got me and at ten o’clock Chloë took pity and woke me with tea and an offer to test me on the differences between Almoravid and Almohad motifs. However, we soon gave it up for a bad job and went out to lock up the sheep and chickens instead.

It was a beautiful night. Bumble and Big, our dogs, rocketed down to the river, barking the trail of a wild boar. The air was light and balmy and suffused with the summer scent of jasmine and wild lavender. It was a night for having not a care in the world and yet I was bowed down with foreboding. A feeling that returned with double intensity when I rose the next morning, slipped on my one

respectable

outfit and set off to Seville.