The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (38 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

No president’s death since Abraham Lincoln had made such a dramatic impact on the American people. Grief-stricken, they simply could not comprehend that the man who had been their president since 1933, who had taken the nation from a series of disasters to the brink of victory in Europe, was actually dead.

7

Mama Truman Visits the White House

A

MONTH AFTER HARRY TRUMAN

was sworn in as president, he sent the Sacred Cow, his personal airplane, to bring his ninety-two-year-old mother from Grandview, Missouri, to Washington for Mother’s Day on Sunday, May 13,

1945. It was her first visit to Washington and her first plane ride. “Mama got a great kick out of the trip,” the president told aides.

Like her son, the mother was a rebel of sorts. The president told her that she could sleep in the bed once occupied by Abraham Lincoln. She balked. Threatened to sleep on the floor. So the son said she would put her in the large ornate Rose Room. Too fancy. She slept in a small adjoining room.

8

GIs’ Best Friend Dies in Battle

F

EW, IF ANY, AMERICANS

had heard of Ie Shima, an obscure flyspeck in the Pacific only three hundred and forty miles from Tokyo. But in the spring of 1945, thousands of American soldiers were locked in a death struggle with Japanese troops who fought to the death. With the GIs was war correspondent Ernie Pyle.

A thousand American correspondents covered some aspects of the global war, but Pyle was the most beloved. He was a hero to countless fighting men. Millions on the home front prayed for his safety.

Ernie never made war glamorous, and he often betrayed his own emotions when he saw young Americans being butchered in battle. He wrote of the nobility of GIs putting their lives on the line while fighting for their country. After hundreds of close brushes with death, Ernie was frail, emaciated, and his hair had gone gray. Still he refused to go home.

On April 18, Pyle was driving to the front on Ie Shima when his jeep was raked with fire from a hidden Japanese machine-gun nest. He was killed by a slug in the head.

Home-front America was shocked by Pyle’s death. This simply couldn’t have happened; there must have been a mistake in the media reporting. But it dawned on Americans that the “GIs’ best friend,” as he was known, had made the supreme sacrifice.

President Harry Truman said: “Nobody knows how many individuals in our armed forces and at home Ernie helped by his writings. But all Americans understand how wisely, how warmheartedly, how honestly he served his country and his profession.”

9

Restrained Joy Breaks Out

M

ORE THAN A HALF-MILLION PEOPLE

gathered in Times Square in New York City to celebrate. Navy blue and Army khaki mixed with civilian browns and grays, standing shoulder to shoulder as they cheered the news flashed by elec

Restrained Joy Breaks Out

195

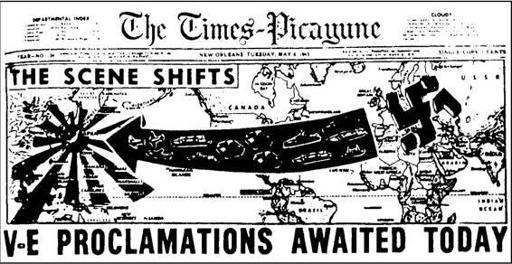

(Times-Picayune)

tric bulbs that beribboned around the New York Times Building. It was May 8, 1945—Victory in Europe Day.

“Just like New Year’s Eve before the war!” the celebrants shouted to one another. Strangers kissed and hugged. Whisky bottles were passed around. Often smiling faces were wet with tears. Confetti fluttered down from the tall structures.

At about ten o’clock that night, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia broadcast an order that Times Square be cleared. “War workers need to get to their midnight shifts,” he said.

People also took to the streets in hundreds of towns large and small. Celebrations in Los Angeles concluded at about 3:00

P

.

M

. after Mayor Fletcher Bowden asked that church bells be pealed.

“This is a time for prayer that the war in the Pacific will soon be ended,” Bowden said. “This is not a holiday.”

In Cleveland, the streets were littered with torn papers and long streamers dangled from office windows draped over streetcar wires. In the suburb of Parma, a man painted a fireplug red, white, and blue.

In Chicago, a gray-haired man went up to a woman behind the cigar counter in the lobby of the Stevens Hotel. “Aren’t you going to celebrate?” he asked. “Celebrate what?” she replied. “I have two sons fighting in the Pacific.”

There were no noisy celebrations in San Francisco. Schools closed early. The Junior Chamber of Commerce sponsored an “On to Tokyo” rally in the Civic Auditorium.

Except for a truckload of boys with musical instruments touring the heart of Des Moines, there was no revelry.

In St. Louis, church leaders held services in Memorial Plaza, and retail stores closed. In Baltimore harbor, there were impromptu celebrations aboard British and Norwegian ships, but the streets were largely empty.

In Boston, workmen tearing down the old New England Mutual Building in Post Office Square tolled the bell in the tower. It was the first time the bell had rung in years.

Minneapolis sounded its central air-raid warning siren atop the Northwestern National bank. Extra policemen were on hand in case celebrations got out of hand. But there were no celebrations, so the extras were sent home.

Many Springfield, Massachusetts, stores draped their show windows with American flags to protect glass from the expected throngs of celebrators. But there were no crowds.

Across home-front America, Victory in Europe Day had been largely subdued except for brief flurries. In Connecticut, an employee of the Seth Thomas clock factory, which had been converted to war production, reflected the mood of most people across the land: “This day really doesn’t mean much to me. When I stop making fuse parts for shells and start making clock parts again, then I’ll celebrate.”

10

Two Old Friends Meet

T

WENTY-FOUR HOURS AFTER V-E DAY,

Navy Lieutenant Cecil Sanders and an old friend from his training days two years earlier met by chance in San Francisco. Both were in the United States on leave after having seen combat in the Pacific as skippers of PT boats, the speedy little craft with the large sting in their tails.

The two young officers had dinner and a few drinks and talked over old times at Northwestern University where they had trained. Later they leisurely strolled about downtown San Francisco and saw several Soviet officers on the streets.

Sanders’s friend said, “Sooner or later, we’re going to have to deal with the Soviet Union.” Seventeen years later, he did—as President John F. Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis.

11

Poll: Hang Hirohito

A

N EDITORIAL HEADLINE

in the Los Angeles Times summed up the situation:

TWO DOWN [HITLER AND MUSSOLINI], ONE TO GO [EMPEROR HIROHITO].

A public opinion poll released on June 1, 1945, disclosed that home-front America wanted the war against Japan to end as quickly as possible, but not

“Your Son Is Close to Death”

197

through some sort of negotiated peace. By a nine-to-one ratio, the people were in favor of continuing the conflict until Japan surrendered unconditionally.

As for the destiny of Emperor Hirohito, whom most Japanese revered as a god, nearly 50 percent of the poll’s respondents wanted him hanged as a “war criminal,” although no one seemed to know precisely what a war criminal was.

12

“Your Son Is Close to Death”

I

N THE HEARTLAND OF AMERICA,

Doran Dole and his wife Bina were going through their daily routine in the small town of Russell, Kansas. Like other Americans, they had offered up prayers of thanks that the war in Europe was concluded. But they were constantly gripped by fear. Their son, twenty-oneyear-old Lieutenant Robert J. Dole, was a patient in Winter General Hospital in Topeka, suffering from horrendous wounds he had received on April 14, 1945, while leading a platoon of the 10th Mountain Division against heavily defended Hill 913 in Italy.

At a field hospital, doctors had found that an exploding shell had destroyed Lieutenant Dole’s right shoulder, fractured vertebras in his neck and spine, and riddled his body with metal slivers. His spinal cord tilted, resulting in the medical diagnosis: “Paralysis complete in all four extremities.”

Army doctors doubted that the lieutenant would live. If he did survive, they concluded, he would never walk again or be able to use his arms. A heavy cast from hips to chin was fashioned on the patient.

Now the young Kansan had to summon another kind of courage with which to engage in a lonely fight to not only survive, but to one day walk again. His weapons were prayer, pluck, and perseverance.

In the weeks ahead, Dole was a patient at the 15th Evacuation Hospital in Florence, Italy; the 70th General Hospital in Casablanca, Morocco; and finally Winter General Hospital in Topeka.

Constantly flat on his back, unable to move his arms and legs, and usually in excruciating pain, Dole could do nothing but stare at the ceiling.

Bina Dole visited her son at Winter General. Seeing him in the body cast, gaunt, and helpless, she broke into tears. Then she steeled her spirit. Never again would she weep in his presence.

“Don’t worry, Mom,” Bob said in a soft, hoarse voice, “I’m going to be back, as good as new.”

In July, Doran Dole received an urgent telephone call from a doctor at Winter General. “You might want to come here,” he was told. “Your son is close to death.”

Doran and Bina rushed to Topeka and kept a lonely vigil over Bob. Doctors had to remove an infected kidney.

Lieutenant Robert J. Dole spent two years in Army hospitals. Parents were told he was near death. (Courtesy of Elizabeth Dole)

Bob fooled the doctors, however: he refused to die. By September, an improvement was evident. Most of the burdensome body cast was hacked off, and he gained feeling in both legs. Helped by nurses and other attendants, he was able to get up, put his feet on the floor, and take a few shaky steps down the hall.

A month later, the Doles were permitted to bring their son home for a short time, back to the house where he had spent most of his boyhood in the family’s basement lodging. Out of her son’s hearing, Bina once broke into sobs and told a daughter, Gloria, “I’m afraid we brought him home to die!”

There was good reason for Bina’s pessimism: her son looked, in the words of a boyhood friend of his, “like death warmed over.” He had left Russell to go to war a vigorous, strapping athlete weighing more than a hundred and ninety pounds. Now his frame was gaunt, he weighed seventy pounds less, and he had to be carried into the house on a stretcher.

Bob remained determined to one day walk again, maybe even regain the use of his shattered arm. So just after Thanksgiving, he joined a few thousand patients at the Percy Jones Medical Center in Battle Creek, Michigan, a facility specializing in amputations, orthopedics, and neurosurgery.

The lieutenant knew that he would be striving for a near miracle, but he was determined to make the effort: he worked hard and long on exercises prescribed by therapists. Then he was stricken with a blood clot, near pneumonia, with a temperature close to 106 degrees. His life was saved by an experimental dose of streptomycin, then a new wonder drug.