The Aeneid (8 page)

“. . . let him be plagued in war by a nation proud in arms, . . .

let him grovel for help and watch his people die

a shameful death! And then, once he has bowed down

to an unjust peace, may he never enjoy his realm

. . . let him die

before his day. . . . ”(4.767-73)

When the Roman world became Christian, Virgil remained as its classic poet, not only because of the fourth

Eclogue,

which many Christians regarded as a prophecy of the birth of Christ, but also because of a recognition of a fellow spirit—

anima naturaliter Christiana,

a naturally Christian spirit he was called by Tertullian, the great Christian figure of second century Carthage. And Virgil’s significance in the European Christian tradition is emphasized by the important part he takes, both in the many borrowings from his work and also in the prominent role he plays himself in the

Divina Commedia

of Dante (1265-1321).

Eclogue,

which many Christians regarded as a prophecy of the birth of Christ, but also because of a recognition of a fellow spirit—

anima naturaliter Christiana,

a naturally Christian spirit he was called by Tertullian, the great Christian figure of second century Carthage. And Virgil’s significance in the European Christian tradition is emphasized by the important part he takes, both in the many borrowings from his work and also in the prominent role he plays himself in the

Divina Commedia

of Dante (1265-1321).

Not only are there striking resemblances between Dante’s account of

Inferno, Purgatorio,

and

Paradiso

and Book 6 of the

Aeneid,

not only does he choose Virgil as his guide through the first two countries of the next world, he thanks him also for the gift of

bello stilo,

which Virgil had given to the Latin language, and which Dante has re-created for the Italian. And recalls of Virgil’s language occur at once as he recognizes the figure before him; he addresses him in a reminiscence of his own

Aeneid,

“

Or se’tu quel Virgilio . . . / che

. . . ?” (

Inferno

1.79-80), “Are you that Virgil who . . . ?” It is a recall of Dido’s question as she realizes who her visitor must be: “

Tune ille Aeneas quem

. . . ?” (1.617). And the reminiscences are not just verbal; subject matter and character are borrowed too. The same Charon ferries spirits across the same river and refuses again to take a living passenger at first. Minos judges the dead; Cerberus must have his “sop.” And there are even wider resemblances—the special place in both poems for suicides, and for those who died for love. And on a broader scale between Elysium and

Paradiso,

between

Purgatorio

and Virgil’s “souls” who are “drilled in punishments, they must pay for their old offenses” (6.854-55), with the difference that in Dante the souls who have finished purgation drink the water of Lethe and go to Paradise, where in Virgil, except for those who go to Elysium, they go, after drinking the water of Lethe, back to life in a fresh incarnation to become the Romans.

Inferno, Purgatorio,

and

Paradiso

and Book 6 of the

Aeneid,

not only does he choose Virgil as his guide through the first two countries of the next world, he thanks him also for the gift of

bello stilo,

which Virgil had given to the Latin language, and which Dante has re-created for the Italian. And recalls of Virgil’s language occur at once as he recognizes the figure before him; he addresses him in a reminiscence of his own

Aeneid,

“

Or se’tu quel Virgilio . . . / che

. . . ?” (

Inferno

1.79-80), “Are you that Virgil who . . . ?” It is a recall of Dido’s question as she realizes who her visitor must be: “

Tune ille Aeneas quem

. . . ?” (1.617). And the reminiscences are not just verbal; subject matter and character are borrowed too. The same Charon ferries spirits across the same river and refuses again to take a living passenger at first. Minos judges the dead; Cerberus must have his “sop.” And there are even wider resemblances—the special place in both poems for suicides, and for those who died for love. And on a broader scale between Elysium and

Paradiso,

between

Purgatorio

and Virgil’s “souls” who are “drilled in punishments, they must pay for their old offenses” (6.854-55), with the difference that in Dante the souls who have finished purgation drink the water of Lethe and go to Paradise, where in Virgil, except for those who go to Elysium, they go, after drinking the water of Lethe, back to life in a fresh incarnation to become the Romans.

And there is one reference to Virgil in Dante that echoes down the centuries to the twentieth. It is the passage in Canto I of

Inferno

(106-8, trans. Robert and Jean Hollander):

Inferno

(106-8, trans. Robert and Jean Hollander):

Di quella umile Italia fia salute

per cui morì la vergine Cammilla,

Eurialo e Turno e Niso di ferute.“He shall be the salvation of low-lying Italy

for which maiden Camilla, Euryalus,

Turnus, and Nisus died of their wounds.”

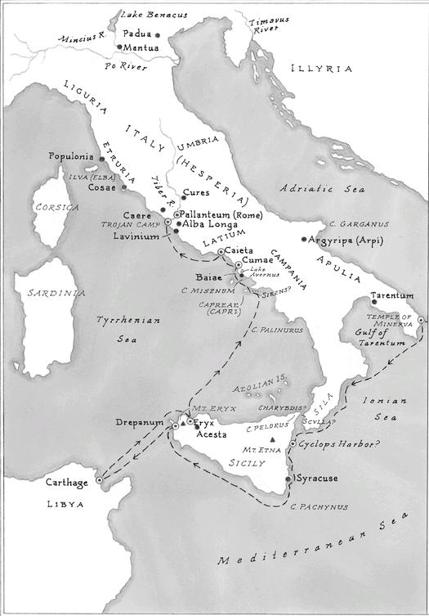

Why Italy is lowly and who her savior is are matters still disputed by scholars, but the phrase “

umile Italia

” is obviously a memory of

Aeneid

3.522-23: “

umilemque videmus / Italiam

”—“and low-lying we see / Italy” (trans. Knox). It is Aeneas’ first sight of Italy, as indeed it looks still to the traveler coming from Greece—a low line on the horizon. And the heroes who have laid down their lives for this Italy fought on both sides. This ter cet of Dante’s, among the most copious of his references to Virgil’s text, was destined to echo down the ages until its appearance in a remarkable twentieth-century context in the Italy of Mussolini, who was trying to restore the warlike image of Roman Italy and make the Mediterranean once more

mare nostrum,

“our sea.”

umile Italia

” is obviously a memory of

Aeneid

3.522-23: “

umilemque videmus / Italiam

”—“and low-lying we see / Italy” (trans. Knox). It is Aeneas’ first sight of Italy, as indeed it looks still to the traveler coming from Greece—a low line on the horizon. And the heroes who have laid down their lives for this Italy fought on both sides. This ter cet of Dante’s, among the most copious of his references to Virgil’s text, was destined to echo down the ages until its appearance in a remarkable twentieth-century context in the Italy of Mussolini, who was trying to restore the warlike image of Roman Italy and make the Mediterranean once more

mare nostrum,

“our sea.”

In this endeavor he made opponents and enemies whom he silenced and punished in various ways. One of his critics and opponents, Carlo Levi, was sent into a sort of exile in a small poverty-stricken town in Calabria, a town so poor that its inhabitants claimed that Christ, on his way through Italy, had stopped at Eboli, and never reached them. In Levi’s somber and beautiful account of his life there, published under the title

Christ Stopped at Eboli

(trs. 1947), he tells how the local Fascist official came to see him, and asked him why on earth he, an educated, talented man, did not support Mussolini’s regime, which aimed at restoring Italy to its old eminence as master of the Mediterranean. His reply was to say that his idea of Italy was different; it was

Christ Stopped at Eboli

(trs. 1947), he tells how the local Fascist official came to see him, and asked him why on earth he, an educated, talented man, did not support Mussolini’s regime, which aimed at restoring Italy to its old eminence as master of the Mediterranean. His reply was to say that his idea of Italy was different; it was

“Di quella umile Italia . . .

per cui morì la vergine Cammilla,

Eurialo e Turno e Niso di ferute.”

Carlo Levi’s reply brought Virgil through Dante into the realities of the modern world, and to compare small things to great, I too brought Virgil back to life in Italy some years later. I consulted the Virgilian lottery in April 1945. The year before, while a captain in the U.S. Army, I had worked with French partisans behind the lines against German troops in Brittany, and after a leave I was finally sent to Italy to work with partisans there. No doubt the OSS moguls in Washington figured that since I had studied Latin at Cambridge I would have no trouble picking up Italian. The partisans this time were on our side of the lines; things had got too difficult for them in the Po Valley and they had come through the mountains. The U.S. Army, very short of what the soldiers called “warm bodies,” since so many of its best units had been called in for the invasion of southern France, armed them and put them under the command of American officers to hold sections of the mountain line where no German breakthrough was expected. I had about twelve hundred of them, in various units ranging from Communist to officers of the crack corps of the Italian army, the Alpini; but they had two things in common—great courage and still greater hatred of Germans. For several months we held the sector, which contained the famous Passo dell’ Abettone, then impassable for wheeled vehicles since the German engineers had blown its sides down. We made frequent long patrols into enemy territory, sometimes bringing back prisoners for interrogation, sometimes passing civilian agents through the lines. In April we were given a small role in the final move north that brought about the German surrender of Italy. The main push was to the left and right of us, where tanks and wheeled vehicles could move—on the coast road to our left and on our right through the Futa Pass to Bologna. We were to attack German positions on the heights opposite us, take the town of Fanano, and then go on to Modena in the valley.

We killed or captured the German troops holding the heights without too many losses, liberated Fanano, and started north on the road to Modena. As we marched along I could not help thinking that the legions of Octavian and Mark Antony had marched and countermarched in these regions in 43 B.C. Like them, we had no wheeled transport; like them, we had no communications (our walkie-talkies had a very short range); like them, we hoisted our weapons onto our shoulders when we forded the Reno River with the water up to our waists.

Every now and then we met a German machine-gun crew holed up in a building that delayed our passage. Usually we too occupied a building to house our machine guns and keep the enemy under fire while we sent out a flanking party to dislodge them. On one of these occasions we occupied a villa off the road that had evidently been hit by one of our bombers; it had not much roof left and the inside was a shambles, but it would do. At one point in the sporadic exchanges of fire I handed over the gun to a sergeant and retreated into the debris of the room to smoke a cigarette. As I looked at the tangled wreckage on the floor I noticed what looked like a book, and investigation with my foot revealed part of its spine, on which I saw, in gold capitals, the letters “MARONIS.” It was a text of Virgil, published by the Roman Academy “IUSSU BENEDICTI MUSSOLINI,” “By Order of Benito Mussolini.” There were not many Italians who would call him “blessed” now; in fact, a few weeks later his blood-stained corpse, together with that of his mistress, Clara Petacci, and that of his right-hand man, Starace, would be hanging upside-down outside a gas station in Milan.

And then I remembered the

Sortes Virgilianae.

I closed my eyes, opened the book at random and put my finger on the page. What I got was not so much a prophecy about my own future as a prophecy for Italy; it was from lines at the end of the first

Georgic

:

Sortes Virgilianae.

I closed my eyes, opened the book at random and put my finger on the page. What I got was not so much a prophecy about my own future as a prophecy for Italy; it was from lines at the end of the first

Georgic

:

. . . a world in ruins . . .

For right and wrong change places; everywhere

So many wars, so many shapes of crime

Confront us; no due honor attends the plow.

The fields, bereft of tillers, are all unkempt . . .

. . . throughout the world

Impious War is raging.(1.500-11)

“A world in ruins.” It was an exact description of the Italy we were fighting in—its railroads and its ancient buildings shattered by Allied aircraft, its elegant bridges blown into the water by the retreating Germans, and its fields sown not with seed by the farmers but with mines by the German engineers.

The fighting stopped; it was time to move on. I tried to get the Virgil into my pack, but it was too big, and I threw it back to the cluttered floor. But I remember thinking: “If I get out of this alive, I’ll go back to the classics, and Virgil especially.” And I did. My first scholarly article, written when I was an assistant professor at Yale, was about the imagery of Book 2 of the

Aeneid,

entitled “The Serpent and the Flame.”

Aeneid,

entitled “The Serpent and the Flame.”

BOOK ONE

Safe Haven After Storm

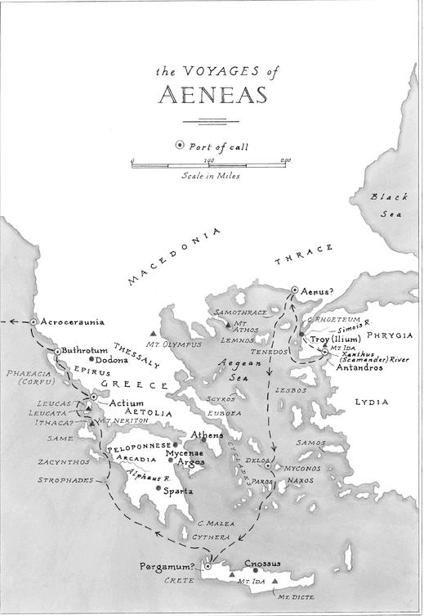

Wars and a man I sing—an exile driven on by Fate,

he was the first to flee the coast of Troy,

destined to reach Lavinian shores and Italian soil,

yet many blows he took on land and sea from the gods above—

thanks to cruel Juno’s relentless rage—and many losses

he bore in battle too, before he could found a city,

bring his gods to Latium, source of the Latin race,

the Alban lords and the high walls of Rome.

Tell me,

Muse, how it all began. Why was Juno outraged?

What could wound the Queen of the Gods with all her power?

Why did she force a man, so famous for his devotion,

to brave such rounds of hardship, bear such trials?

Can such rage inflame the immortals’ hearts?

he was the first to flee the coast of Troy,

destined to reach Lavinian shores and Italian soil,

yet many blows he took on land and sea from the gods above—

thanks to cruel Juno’s relentless rage—and many losses

he bore in battle too, before he could found a city,

bring his gods to Latium, source of the Latin race,

the Alban lords and the high walls of Rome.

Tell me,

Muse, how it all began. Why was Juno outraged?

What could wound the Queen of the Gods with all her power?

Why did she force a man, so famous for his devotion,

to brave such rounds of hardship, bear such trials?

Can such rage inflame the immortals’ hearts?

There was an ancient city held by Tyrian settlers,

Carthage, facing Italy and the Tiber River’s mouth

but far away—a rich city trained and fierce in war.

Juno loved it, they say, beyond all other lands

in the world, even beloved Samos, second best.

Here she kept her armor, here her chariot too,

and Carthage would rule the nations of the earth

if only the Fates were willing. This was Juno’s goal

from the start, and so she nursed her city’s strength.

But she heard a race of men, sprung of Trojan blood,

would one day topple down her Tyrian stronghold,

breed an arrogant people ruling far and wide,

proud in battle, destined to plunder Libya.

So the Fates were spinning out the future . . .

This was Juno’s fear

and the goddess never forgot the old campaign

that she had waged at Troy for her beloved Argos.

No, not even now would the causes of her rage,

her bitter sorrows drop from the goddess’ mind.

They festered deep within her, galled her still:

the Judgment of Paris, the unjust slight to her beauty,

the Trojan stock she loathed, the honors showered on Ganymede

ravished to the skies. Her fury inflamed by all this,

the daughter of Saturn drove over endless oceans

Trojans left by the Greeks and brute Achilles.

Juno kept them far from Latium, forced by the Fates

to wander round the seas of the world, year in, year out.

Such a long hard labor it was to found the Roman people.

Carthage, facing Italy and the Tiber River’s mouth

but far away—a rich city trained and fierce in war.

Juno loved it, they say, beyond all other lands

in the world, even beloved Samos, second best.

Here she kept her armor, here her chariot too,

and Carthage would rule the nations of the earth

if only the Fates were willing. This was Juno’s goal

from the start, and so she nursed her city’s strength.

But she heard a race of men, sprung of Trojan blood,

would one day topple down her Tyrian stronghold,

breed an arrogant people ruling far and wide,

proud in battle, destined to plunder Libya.

So the Fates were spinning out the future . . .

This was Juno’s fear

and the goddess never forgot the old campaign

that she had waged at Troy for her beloved Argos.

No, not even now would the causes of her rage,

her bitter sorrows drop from the goddess’ mind.

They festered deep within her, galled her still:

the Judgment of Paris, the unjust slight to her beauty,

the Trojan stock she loathed, the honors showered on Ganymede

ravished to the skies. Her fury inflamed by all this,

the daughter of Saturn drove over endless oceans

Trojans left by the Greeks and brute Achilles.

Juno kept them far from Latium, forced by the Fates

to wander round the seas of the world, year in, year out.

Such a long hard labor it was to found the Roman people.

Other books

8 Antiques Con by Barbara Allan

The Last Boy by Jane Leavy

Sudden Impact by Lesley Choyce

The Ghost of Greenwich Village: A Novel by Lorna Graham

A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries by Kaylie Jones

Kiss Me Deadly by Michele Hauf

Crossing the Line by Clinton McKinzie

Surrounded by Enemies by Bryce Zabel

Blonde Bombshell by Tom Holt

Jessie by Lori Wick