The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton (26 page)

Read The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton Online

Authors: Robert J. Begiebing

The second occurrence I took to be equally signal: Mr. Spooner sent my completed study in self-portraiture (the very study Mr. Neal had found in the studio) to the Athenaeum, where it was exhibited for sale among the most respected painters in the city of that day. It sold to a patron who wished to be anonymous. Thereby was I finally inaugurated in 1843 as a

fine

artistâno longer a mere traveling face-maker nor a mere pupil, and it seemed that I had before me only the necessity of study in Europe to complete my years of apprenticeship.

Looking back on that time, I see now that if these accomplishments were substantial, my high confidence was largely the enthusiasm of a young woman, not yet out of her twenties, whose vision of her future was still tinted by the rainbow hues of youthful promise.

NINETEEN

My Italian adventure

To Spring; or, Concerning the Ancient Myths

And are you living yet,

O sacred Nature? May our human ears,

So long unused, catch that maternal voice?

The brooks were once a home for the white nymphs,

Their shelter and their glass

The liquid springs; and the high mountain ridges

To secret dancing of immortal feet

Trembled, and the deep forests (now

The lonely haunt of winds). The shepherd boy

Who sought at noontide the uncertain shade

And led his thirsty lambs

Down to the flowery river's brink, might hear

Sounding along those banks

The rustic Pan's shrill song or, struck with wonder,

Gaze on the rippling waters, for unrevealed

The quiver-bearing goddess

Went down to the warm flood, to cleanse away,

After the bloodstained hunt, immodest dust

From her snowy flank and virgin arms⦠.

And legend told you,

Musical bird, well-versed

In human deeds, amid leafy coverts

Singing now Spring is born again, you mourned

To the dark silent air,

In stillness of the fields, your ancient wrongs,

And all the dreadful tale of your revenge

In that wan day when wrath and pity met.

But we can claim no kindred

Now with your race; nor human grief informs

Your varied notes; darkling valley hides you,

Free from all guiltâthe less belov'd for that.

âGiacomo Leopardi, January, 1822

In March of 1843 the world did not end. The revival meetings in cities, the preachers haranguing thousands of townsfolk in their enormous traveling tents, the throngs closing their shops and houses (many giving away all worldly goods) and standing about in the fields wearing their muslin “ascension robes,” and the suicides and disrupted familiesâall came to naught.

The thousands who had converted to the millenarian Millerite calculations for the end of the world were, however, not to be so easily discouraged. New calculations were made immediately, and embraced. The world would end, in fact, on October 20, 1844. One did not have to throw away his sign proclaiming

“This shop is closed in honor of the King of kings. Get ready, friends, to crown Him Lord of All.”

One only had to tuck the sign away for a year or so. The pitch and volume of this madness increased and seemed to suck away intelligence and skepticism. Soon a Millerite Tabernacle opened in Boston, the very center of American learning.

I

RECALLED EVEN

Miss Fuller once saying that she would be willing to accept the millennium in order to unfetter and enlarge and exalt our minds. But I doubted her faith in such a coming, for she had little patience with dogma and zealotry of any kind, or in their missionaries. The transcendent, which she once described as “that beyond which we can conceive,” was to be manifest, if I understood her correctly, otherwise.

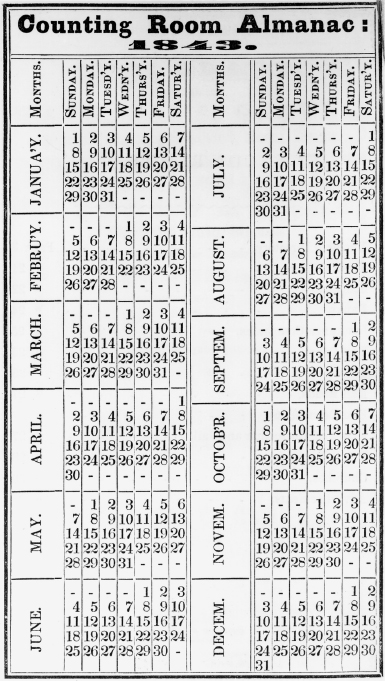

“Counting Room Almanac, 1843,” from

Worcester Business Directory, 1842â43.

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

I began, however, to despair of my compatriots. But I was soon to be out of all that, for just as the leaves were turning once again that year, a long-awaited opportunity arose. Mr. Spooner had received a commission from the American Academy for a series of studies in the draughtsmanship and compositional techniques of certain Italian masters, to be produced as a lavish instructional book in folio. He garnered several other handsome commissions for paintings while in Italy as well, and he, Mrs. Spooner, and Gibbon had begun to plan for their journey. I was invited to accompany them, as was Julian, but his mother's health was failing again and he was for the moment ill-equipped to finance his own expenses abroad.

The central question, of course, was how I should pay for my travels. Not wishing to place myself in any greater debt to the Spooners, who had been most generous toward me in every way, I tried to take the matter into my own hands. I gave up my private rooms, took on additional pupils, and completed and sold two landscapes for a good price through Mr. Spooner's own sales agent. In short, every vital energy I now bent toward garnering funds to wing me abroad.

I returned to Mr. Spooner's studio and to the private room I had occupied in their house upon first returning to Boston. Following much effort on their part, both Mr. Spooner and Mr. Dana helped me procure two commissions to be executed while abroad, and as my reputation had gradually grown, I found myself in some demand now among a better sort of patron. Mostly they wanted my renderings of children and women, and at a range of prices more reasonable than they could negotiate of the fashionable portraitists.

Under these new circumstances I could of course no longer entertain Chas Sparhawk. He had been especially vehement in advising against my returning to “the unhealthy influences of that Spooner domicile.” And Chas knew of my plans to leave this life in America behind me. There was discord between us now, and that rift caused me much anguish and self-reproach. Still, I believed that there was no hope for it if I were ever to live and study in Italy.

In spite of the frightening financial uncertainties, I believed my time had now come, if it ever were to come, and I must dare to leave my homeland.

I had distressing incitements as well: there was to be an element of decampment in my own passage abroad. For although Mr. Dana told me in the spring that to his knowledge official pursuit of Tom in the Dudley affair had ceased, I did afterward glimpse from time to time Miss Gretchel or Mr. Wellington among the throngs of the city, and I began to suspect they were keeping watch on me, as if they hoped I would lead them to Tom, who, perhaps they believed, had not fled overseas. But of course he had, and I hoped they would tire of their secretiveness well before I sailed for Europe.

Of my afflictions from my rift with Chas, Mr. Spooner politely suggested that Chas had somehow mesmerized me into a kind of dependency, “a strange and unseemly servility.”

“Even were it so,” I said, “I can't believe I'd have been wholly insensible to his machinations.”

“I'm not talking about some display of hocus-pocus and such mountebankery as he uses to entrance the coarser crowd,” Mr. Spooner said. “His methods would have been far more subtle, and for purposes other than monetary, with you.”

“Balderdash, sir!”

“Maybe so, Allegra. Still, as you yourself have said, your years of renunciation after the death of your husband have been necessary to your development and independence as much as for your grief. But have those years not also readied you to be all the more pliable in the hands of such a man?”

“Mr. Spooner, am I some witless woman of fashion falling unawares and overheated, through the shock of her renunciations, into the hands of the first man she finds attractive? Would you not give me a little credit for consciousness?” I laughed, and he joined me. But he never came to believe in Chas's “innocence” as to the strength of my affections for him. I simply did everything I could to put Chas Sparhawk out of my mind. I was, moreover, engrossed in my work. I was, in short, little more than a drudge all these days and weeks.

Mostly, such drudgery was the effect of the necessary pace of my earnings, but as Mr. Spooner had always warned his protégés, there is no avoiding the necessity of the artisan in every artist, that sheer labor of craftsmanship that must accompany one's inspirations or intuitionsâhowever magnificent. Only one's brush, or chisel, he liked to say, can speak for the spirit. “The rest is dilettantism, the humbug of chatterboxes and theorists who accomplish nothing. Do you imagine that the masters we so greatly admire spent much of their time debating the finer points of art? No, they went like loyal workers into their vineyards, or steady burghers into their shops at daybreak, and labored in solitude. Even Rubens,” he never tired of reminding us, “regulated his affairs with precision: receiving company only at stated times, taking regular exercise, and painting only while someone read to him from a classic work of poetry or history.”

Out of my own steady labors, meagre funds accumulated, but I was sorry to see that Julian had less fortune in that regard. There were days in the heat of summer when I felt like some chaste and lowly priestess, both buoyed and pained by steadfast renunciations that friend Julian was unable to match. By swearing herself to work and celibacy, I began to see, a woman might not only free herself from lengthy entanglements of love, but also extricate her way of life from blame and petty gossip (and the ill will of others that was sure to follow), from, in brief, that pettiness which darkens the parlors as much as the ateliers of Boston.

A

S I SAY, HOWEVER

, it was in October of 1843 that I seized the opportunity to sail for Europe. Our ultimate destination was to be Florence, Italy. And I shall bring us, reader, to that new home in short order. But unexpected misfortune as well as the journey itself brought Mr. Spooner and me into a new, daily relation that prepared me for my Florentine days and nightsâas if here my very substance were to be furrowed and reshaped.

Shortly before their long-planned departure, Mrs. Spooner took ill, grievously at first, so they had thought to cancel the journey and, if possible, postpone the important commissions. But on the verge of rearranging all their extensive plans, Mrs. Spooner began to improve. So Mr. Spooner procrastinated a bit longer. As the day approached, she insisted that I go on her passage, however, and that she would follow once she had fully recovered and felt up to the rigors of the journey. There was much heated discussion and difficulty over these arrangements, but the upshot was that Mr. Spooner and I sailed for Europe only on the condition that Gibbon stay to look after his mother, who was by then clearly improving, and later accompany her abroad to join us. Julian did not have sufficient funds to take Gibbon's place, nor did his mother's condition improve. But I was able to reimburse the Spooners for my passage at that time, and I resolved to repay them for the remainder of my own travel and living expenses while in Europe.

We sailed from New York to Paris. Never had I been at sea with no land in sight, where the ocean looks not at all as it does from land: the blackness of nearby waters, the intense blue but a little distance away, the little rainbows either side of the ship. Mr. Spooner continually remarked on the improvements and conveniences of steamship travel. No more leaning to leeward, no seasickness, no bumping of blocks or strong odors of shipboard life. Merely the quiet parties of whist, chess, and backgammon, the smooth gaiety of a handsome saloon of brilliant lights and popping champagne corks.

We spent many hours on deck, Mr. Spooner and I, enchanted by the beauty and power of the open ocean. When we were not enjoying such enchantment, or not dining and conversing with other passengers, we improved our time below, in our tiny staterooms, reading the collection of books we had brought along, whose most common theme was the mastersâthe times and places and lives behind their works. All this while my mentor, God bless him, was attentive and companionable. Often I thought how different it would have been enduring all these miles entirely alone.

Late one morning while I was reading, he knocked on my door and announced: “Land in sight, Allegra! England.”

It was the first land we had seen for more than a fortnight, with great rocks along the coast and a few villages spotting the green hills beyond, which had the look of hill pastures. Many other ships and boats were about us now and remained for nearly the entire day as we stood, finally, just off shore. At first there was a mist near shore, and the sun kept striking here and there on a pasture or cluster of cottages, illuminating them beautifully as if for very show.

We eventually moved toward the Isle of Wightâat first a long line of pale, almost fantastic rocks reaching out toward us, later becoming green hills again, and, shortly, woods. By dusk we were at Southhampton and disembarked some passengers into the beautiful, mellow lamplight that shone their way. After I returned to my room to sleep, I dreamed of these lamps, and of these rocks and green pastures again and again, and in the morning I thought I might paint what I had seen, but there was no time. After daybreak, we were close to France, the sea voyage over, and the voyage by land about to begin.

The little French steamboats took us ashore, and after the delays of the Custom House and final good-byes to some fellow passengers, we set off for Paris in a landscape of gardens and board-and-plaster houses, reaching the city none too soon for the fatigue and grime of travel. Here, next to Mr. Spooner's room, in my own little room of thick carpets and marble slabs, a French clock over the fireplace, a large mirror and thick curtains, I lived pleasantly but dearly, for it seems impossible to economize in Paris. We knew we should have to keep our stay brief. We would but rest a while before moving on to Chalons, Lyons, Marseille, Leghorn, and finally Florence.