The Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (70 page)

Read The Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes Online

Authors: Arthur Conan Doyle

âIt was a long document, written in the French language, and containing twenty-six separate articles.I copied as quickly as I could, but at nine o'clock I had only done nine articles, and it seemed hopeless for me to attempt to catch my train. I was feeling drowsy and stupid, partly from my dinner and also from the effects of a long day's work. A cup of coffee would clear my brain. A commissionaire remains all

night in a little lodge at the foot of the stairs, and is in the habit of making coffee at his spirit-lamp for any of the officials who may be working overtime.I rang the bell, therefore, to summon him.

âTo my surprise, it was a woman who answered the summons, a large, coarse-faced, elderly woman, in an apron. She explained that she was the commissionaire's wife, who did the charing, and I gave her the order for the coffee.

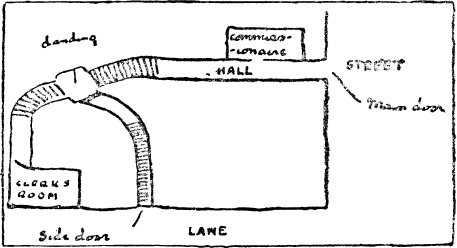

âI wrote two more articles, and then, feeling more drowsy than ever, I rose and walked up and down the room to stretch my legs. My coffee had not yet come, and I wondered what the cause of the delay could be. Opening the door, I started down the corridor to find out. There was a straight passage dimly lit which led from the room in which I had been working, and was the only exit from it. It ended in a curving staircase, with the commissionaire's lodge in the passage at the bottom. Half-way down this staircase is a small landing, with another passage running into it at right angles. The second one leads, by means of a second small stair, to a side door used by servants, and also as a short cut by clerks when coming from Charles Street.

10

âHere is a rough chart of the place.'

âThank you. I think I quite follow you,' said Sherlock Holmes.

âIt is of the utmost importance that you should notice this point. I went down the stairs and into the hall, where I found the commissionaire

fast asleep in his box, with the kettle boiling furiously upon the spirit-lamp, for the water was spurting over the floor. I had put out my hand and was about to shake the man, who was still sleeping soundly, when a bell over his head rang loudly, and he woke with a start.

â “Mr Phelps, sir!” said he, looking at me in bewilderment.

â “I came down to see if my coffee was ready.”

â “I was boiling the kettle when I fell asleep, sir.” He looked at me and then up at the still quivering bell, with an ever-growing astonishment upon his face.

â “If you was here, sir, who rang the bell?” he asked.

â “The bell!” I said. “What bell is it?”

â “It's the bell of the room you were working in.”

âA cold hand seemed to close round my heart. Someone, then, was in that room where my precious treaty lay upon the table. I ran frantically up the stairs and along the passage. There was no one in the corridor, Mr Holmes. There was no one in the room. All was exactly as I left it, save only that the papers committed to my care had been taken from the desk on which they lay. The copy was there and the original was gone.'

Holmes sat up in his chair and rubbed his hands. I could see that the problem was entirely to his heart.

âPray, what did you do then?' he murmured.

âI recognized in an instant that the thief must have come up the stairs from the side door. Of course, I must have met him if he had come the other way.'

âYou were satisfied that he could not have been concealed in the room all the time, or in the corridor which you have just described as dimly lighted?'

âIt is absolutely impossible. A rat could not conceal himself either in the room or the corridor. There is no cover at all.'

âThank you. Pray proceed.'

âThe commissionaire, seeing by my pale face that something was to be feared, had followed me upstairs. Now we both rushed along the corridor and down the steep steps which led to Charles Street. The door at the bottom was closed but unlocked. We flung it open and

rushed out. I can distinctly remember that as we did so there came three chimes from a neighbouring church. It was a quarter to ten.'

âThat is of enormous importance,' said Holmes, making a note upon his shirt cuff.

âThe night was very dark, and a thin, warm rain was falling. There was no one in Charles Street, but a great traffic was going on, as usual, in Whitehall, at the extremity. We rushed along the pavement, bareheaded as we were, and at the far corner we found a policeman standing.

â “A robbery has been committed,” I gasped. “A document of immense value has been stolen from the Foreign Office. Has anyone passed this way?”

â “I have been standing here for a quarter of an hour, sir,” said he; “only one person has passed during that time â a woman, tall and elderly, with a Paisley shawl.”

â “Ah, that is only my wife,” cried the commissionaire. “Has no one else passed?”

â “No one.”

â “Then it must be the other way that the thief took,” cried the fellow, tugging at my sleeve.

âBut I was not satisfied, and the attempts which he made to draw me away increased my suspicions.

â “Which way did the woman go?” I cried.

â “I don't know, sir.I noticed her pass, but I had no special reason for watching her. She seemed to be in a hurry.”

â “How long ago was it?”

â “Oh, not very many minutes.”

â “Within the last five?”

â “Well, it could not be more than five.”

â “You're only wasting your time, sir, and every minute now is of importance,” cried the commissionaire. “Take my word for it that my old woman has nothing to do with it, and come down to the other end of the street. Well, if you won't, I will,” and with that he rushed off in the other direction.

âBut I was after him in an instant and caught him by the sleeve.

â “Where do you live?” said I.

â “No. 16, Ivy Lane,

11

Brixton,” he answered; “but don't let yourself be drawn away upon a false scent, Mr Phelps. Come to the other end of the street, and let us see if we can hear of anything.”

âNothing was to be lost by following his advice. With the policeman we both hurried down, but only to find the street full of traffic, many people coming and going, but all only too eager to get to a place of safety upon so wet a night. There was no lounger who could tell us who had passed.

âThen we returned to the office, and searched the stairs and the passage without result. The corridor which led to the room was laid down with a kind of creamy linoleum which shows an impression very easily. We examined it very carefully, but found no outline of any footmark.'

âHad it been raining all the evening?'

âSince about seven.'

âHow is it, then, that the woman who came into the room about nine left no traces with her muddy boots?'

âI am glad you raise the point. It occurred to me at the time. The charwomen are in the habit of taking off their boots at the commissionaire's office, and putting on list slippers.'

âThat is very clear. There were no marks, then, though the night was a wet one? The chain of events is certainly one of extraordinary interest. What did you do next?'

âWe examined the room also. There was no possibility of a secret door, and the windows are quite thirty feet from the ground. Both of them were fastened on the inside. The carpet prevents any possibility of a trap-door, and the ceiling is of the ordinary whitewashed kind. I will pledge my life that whoever stole my papers could only have come through the door.'

âHow about the fireplace?'

âThey use none. There is a stove. The bell-rope hangs from the wire just to the right of my desk. Whoever rang it must have come right up to the desk to do it. But why should any criminal wish to ring the bell? It is a most insoluble mystery.'

âCertainly the incident was unusual. What were your next steps? You examined the room, I presume, to see if the intruder had left any

traces â any cigar end, or dropped glove, or hairpin, or other trifle?'

âThere was nothing of the sort.'

âNo smell?'

âWell, we never thought of that.'

âAh, a scent of tobacco would have been worth a great deal to us in such an investigation.'

âI never smoke myself, so I think I should have observed it if there had been any smell of tobacco. There was absolutely no clue of any kind. The only tangible fact was that the commissionaire's wife â Mrs Tangey was the name â had hurried out of the place. He could give no explanation save that it was about the time when the woman always went home. The policeman and I agreed that our best plan would be to seize the woman before she could get rid of the papers, presuming that she had them.

âThe alarm had reached Scotland Yard by this time, and Mr Forbes, the detective, came round at once and took up the case with a great deal of energy. We hired a hansom, and in half an hour we were at the address which had been given to us. A young woman opened the door, who proved to be Mrs Tangey's eldest daughter. Her mother had not come back yet, and we were shown into the front room to wait.

âAbout ten minutes later a knock came at the door, and here we made the one serious mistake for which I blame myself. Instead of opening the door ourselves we allowed the girl to do so. We heard her say, “Mother, there are two men in the house waiting to see you,” and an instant afterwards we heard the patter of feet rushing down the passage. Forbes flung open the door, and we both ran into the back room or kitchen, but the woman had got there before us. She stared at us with defiant eyes, and then suddenly recognizing me, an expression of absolute astonishment came over her face.

â “Why, if it isn't Mr Phelps, of the office!” she cried.

â “Come, come, who did you think we were when you ran away from us?” asked my companion.

â “I thought you were the brokers,” said she. “We've had some trouble with a tradesman.”

â “That's not quite good enough,” answered Forbes. “We have

reason to believe that you have taken a paper of importance from the Foreign Office, and that you ran in here to dispose of it. You must come back with us to Scotland Yard to be searched.”

âIt was in vain that she protested and resisted. A four-wheeler was brought, and we all three drove back in it. We had first made an examination of the kitchen, and especially of the kitchen fire, to see whether she might have made away with the papers during the instant that she was alone. There were no signs, however, of any ashes or scraps. When we reached Scotland Yard she was handed over at once to the female searcher. I waited in an agony of suspense until she came back with her report. There were no signs of the papers.

âThen, for the first time, the horror of my situation came in its full force upon me. Hitherto I had been acting, and action had numbed thought.I had been so confident of regaining the treaty at once that I had not dared to think of what would be the consequence if I failed to do so. But now there was nothing more to be done, and I had leisure to realize my position. It was horrible! Watson there would tell you that I was a nervous, sensitive boy at school. It is my nature. I thought of my uncle and of his colleagues in the Cabinet, of the shame which I had brought upon him, upon myself, upon everyone connected with me. What though I was the victim of an extraordinary accident? No allowance is made for accidents where diplomatic interests are at stake. I was ruined; shamefully, hopelessly ruined. I don't know what I did. I fancy I must have made a scene. I have a dim recollection of a group of officials who crowded round me endeavouring to soothe me. One of them drove down with me to Waterloo and saw me into the Woking train. I believe that he would have come all the way had it not been that Dr Ferrier, who lives near me, was going down by that very train. The doctor most kindly took charge of me, and it was well he did so, for I had a fit in the station, and before we reached home I was practically a raving maniac.

âYou can imagine the state of things here when they were roused from their beds by the doctor' sringing, and found me in this condition. Poor Annie here and my mother were broken-hearted. Dr Ferrier had just heard enough from the detective at the station to be able to give an idea of what had happened, and his story did not mend matters. It

was evident to all that I was in for along illness, so Joseph was bundled out of this cheery bedroom, and it was turned into a sick-room for me. Here I have lain, Mr Holmes, for over nine weeks, unconscious, and raving with brain fever. If it had not been for Miss Harrison here and for the doctor's care I should not be speaking to you now. She has nursed me by day, and a hired nurse has looked after me by night, for in my mad fits I was capable of anything. Slowly my reason has cleared, but it is only during the last three days that my memory has quite returned. Sometimes I wish that it never had. The first thing I did was to wire to Mr Forbes, who had the case in hand. He came out and assured me that though everything has been done, no trace of a clue has been discovered. The commissionaire and his wife have been examined in every way without any light being thrown upon the matter. The suspicions of the police then rested upon young Gorot, who, as you may remember, stayed overtime in the office that night. His remaining behind and his French name were really the only two points which could suggest suspicion; but as a matter of fact, I did not begin work until he had gone, and his people are of Huguenot extraction,

12

but as English in sympathy and tradition as you and I are. Nothing was found to implicate him in any way, and there the matter dropped. I turn to you, Mr Holmes, as absolutely my last hope. If you fail me, then my honour as well as my position are for ever forfeited.'