The Act of Creation (65 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

development; in the adult they are superseded by the integrative action

of the nervous system -- unless the embryonic potentials are reactivated

by regenerative needs. Similarly, the adult's mental co-ordination relies

on conscious, verbalized, 'logical' codes; not on the quasi 'embryonic'

(infantile, pre-causal) potentials of the unconscious; again unless these

are revived under the creative stress. Physical regenerations strike

us as 'spectacular pieces of magic' because they derive from prenatal

skills; and creative inspirations are equally mysterious because they

derive from levels which predate the conscious mind. As Polànyi

wrote (in a different context): 'The highest forms of originality are

far more closely akin to the lowest biotic performances than the external

circumstances would indicate.' [11]

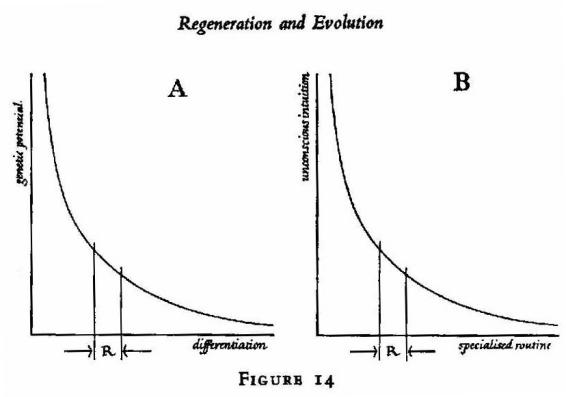

way the complementary factors in the

reculer pour mieux sauter

phenomenon. In A, increase in tissue-differentiation entails a reciprocal

decrease of genetic multipotentiality. In B, an analogous reciprocity

prevails between unconscious intuitions and automatized routines --

or, if you like, between fluid imagery and 'misplaced concreteness'. R

indicates the 'regenerative span'. (The curve in A should of course have

breaks and a series of discrete steps.)

It could be objected that structural regenerations merely restore

the

status quo ante

whereas mental reorganization leads to an

advance. But in the first place this is not always the case. Psychotherapy

aims at correcting 'faulty integrations' caused by traumatic experiences

-- at restoring normality. In the second place the biological evolution

of the species with which we are concerned has to all intents and

purposes come to a standstill, whereas mental evolution continues,

and its vehicle is precisely the creative individual. The Eureka

process is a mental mutation, perpetuated by social inheritance. Its

biological equivalent are the genetic mutations which carried the

existing species up the evolutionary ladder. Now a mutation -- whatever

its unknown cause -- is no doubt a re-moulding of previous structures,

based on a de-differentiation and reintegration of the otherwise rigid

genetic code. The transformations of fins into legs, legs into arms,

arms into wings, gills into lungs, scales into feathers, etc., while

preserving certain basic structural patterns (see, for instance, d'Arcy

Thompson's

On Growth and Form

) were eminently 'witty' answers

to the challenges of environment. It seems obvious that the dramatic

release, at periods of adaptative radiations, of unexplored morphogenetic

potentials by a re-shuffling of molecules in the genetic code, resulting

in the de-differentiation and reintegration of structures like limbs into

wings, is of the very essence of the evolutionary process. After all,

'ontogenesis and regenesis are components of a common mechanism', [12]

which must have a phylogenetic origin.

In Book One,

Chapter XX

, I have mentioned the

perennial myth of the prophet's and hero's temporary isolation and

retreat from human society -- followed by his triumphant return endowed

with new powers. Buddha and Mohamed go out into the desert; Joseph is

thrown into the well; Jesus is resurrected from the tomb. Jung's 'death

and rebirth' motif, Toynbee's 'withdrawal and return' reflect the same

archetypal motif. It seems that

reculer pour mieux sauter

is a

principle of universal validity in the evolution of species, cultures,

and individuals, guiding their progression by feedback from the past.

p. 454

. It is still an open question, however,

whether or how much undifferentiated 'reserve cells' (as in lower animals)

contribute material to the blastema.

p. 454

. It seems that the initial role of

the nervous system is to determine the main axis of the regenerate --

that it acts, not as an inductor, but as a trophic agent. At the later,

anabolic stages of the process no nerve supply is needed -- as denervation

experiments show.

p. 456

. This, actually, is the only clearly

demonstrated case of metaplasia among higher animals.

p. 459

. About the ways how this is achieved,

cf. McCulloch in the Hixon Symposium, p. 56.

represented by an ascending hierarchy of spatial levels perpendicular

to the time axis. In spite of the perplexing diversity of phenomena on

different levels -- cleavage, gastrulation, induction, neuro-genesis --

certain basic principles were seen to operate on every level throughout

the hierarchy. Principles (or 'laws of nature') can only be described

in symbolic language of one kind or another. The language used in the

present theory is based on four key-concepts: motivation, code, matrix,

and environment. Since these are assumed to operate in a hierarchic

framework, the dichotomy of self-asserting and participatory tendencies

of behaviour on all levels need not be separately postulated, but derives

logically, as it were, from the dual character of every sub-whole as a

sub-ordinate and supra-ordinate entity. Let me now recapitulate some of

the main points which have emerged from the previous chapters, taken in

conjunction with

Book One

:

J. Needham's tongue-in-the-cheek phrase about 'the striving of the

blastula to grow into a chicken' indicates the directiveness of the

morphogenetic process and its equifinal, regulative properties, which

become particularly evident under adverse conditions. These properties

represent the genetic precursors of the motivational drives, needs,

and goal-directedness of the adult animal; during maturation, the former

shade into the latter, and there is no sharp dividing line between them.

'whole'. Facing downward or outward in the hierarchy, it behaves as an

autonomous whole; facing upward or inward, it behaves as a dependent part

which is inhibited or triggered into action by higher controls. One might

call this the 'Janus principle' in organic (and social) hierarchies.

autonomous

and

spontaneous

activities. The principle of

autonomy is asserted on every level; from cell-organelles functioning as

power plants or motor units, through the self-differentiating activities

of the morphogenetic field, to the autonomous regulations of organs and

organ system. In the motor hierarchy, it is reflected at every stage, from

the muscle's selective response to specific excitation-patterns, through

the stubborn behaviour of the reversed newt limb, to the unalterable

features in a person's gait or handwriting. I have briefly mentioned (Book

One, Chapters

XIII

,

XXI

),

and shall discuss in more detail later, autonomous mechanism in perceptual

organization -- visual constancies, the automatic filtering, analysing,

generalizing of the input. Lastly, thinking and communicating are based

on hierarchically ordered, autonomous patterns of enunciation, grammar,

logic, mathematical operations, universes of discourse.

dynamic

aspect of the part's autonomy is manifested in

its apparently spontaneous, unprovoked rhythmic activities which are

'modified but not created by the environmental input' -- a statement

which equally applies to morphogenesis, to intrinsic motor patterns,

to the spontaneous discharges of unstimulated sensory receptors, the

electric pulses of the unstimulated brain, to drives in the absence of

external stimuli or to communications addressed to imaginary audiences.

'self-assertive' aspect of part-behaviour.

which may be said to represent the interests of the whole vis-à-vis

the part in question. The controls are largely of an inhibitory or

restraining character, to prevent overloading of information channels,

over-shooting of responses, confusion and redundancy in general; while

the activation of the part is effected by signals of the trigger-release

type. During morphogenesis, control is exercised by the suppression of

unrequired, and the release of required genetic potentials; in the mature

organism by interlacing multiple hierarchies of nervous and circulatory

processes, and biochemical gradients.

in supra-ordination to their own parts, (b) in sub-ordination to their

controlling agency, and (c) in co-ordination with their environment.

the environment of the nucleus is cytoplasm; on the level of the

morphogenetic field, the environment of one cell-population is another

cell-population; each organ in the adult animal is bathed in body-fluids

which constitute its environment. The structure and function of any

sub-whole is

determined

by (a) and (b) -- its intrinsic pattern

and its controls in the 'vertical' hierarchy to which it belongs; but it

is also

affected

by inputs and feedbacks from its 'horizontal'

environment, as it were -- the lie of the land. The difference between

(a) and (b) on the one hand, and (c) on the other is that the former

determine the invariant pattern of the operation, (c) only its variable

details. To mention a few examples: feedback from the cytoplasm to the

genetic blue-print co-determines into which variety of specialized cell

that particular unit will develop; but it does not alter the blue-print

itself. Inductor substances in the immediate environment of a tissue

will promote its differentiation into an organ -- but only within the

limits of the tissue's 'competence'. Environmental hazards decide the

neuro-muscular connections in the grafted salamander-limb, but its

functional co-ordination remains unaffected by it: it is controlled by

its 'vertical' hierarchy, and the lie of the land in the scar-tissue

determines only the local 'tactics' of the outgrowing nerve-filaments.

two types of 'input'. The first consists of specific trigger signals

from its superior controls in the hierarchy; the second are inputs

and feedbacks from more or less random events in its environment. But

I must stress again that the meaning of the word 'environment' depends

on the hierarchic level to which it is applied. The environment of John

driving his car is the traffic stream around him. The environment of

John's right foot is the brake-pedal on which it rests. Let us call

the former an environment on the t-level, where t stands for the top

of the hierarchy controlling the various sensory, motor, and cognitive

processes which constitute the skill of driving; then the brake-pedal

will be an environment on the, say, t-minus-4 level. Now John approaches

a sign which reads 'Halt -- Road Works Ahead'. This input is analysed and

relayed by various stations of the perceptual and cognitive hierarchy,

and is eventually re-coded into a 'sign releaser' which triggers off the

pre-set patterns of slow-down-to-a-halt behaviour on lower echelons of

the motor hierarchy. Thus an

environmental

input on the t-level has

been transformed into a specific trigger signal in a 'vertical' hierarchy;

in other words a 'category c' input on a higher level has been translated

into a 'category b' input on a lower level, activating the autonomous

pattern of the slowing-down skill. This consists in several sub-skills:

braking, steadying the wheel, going into neutral gear at the proper

moment. The foot on the brake-pedal is not responding to the 'Halt' signal

from the environment; it is responding to a specific 'excitation-clang'

travelling down John's spinal cord. But the foot's pre-set response is

modified by feedback from the environment on its own level: the 'feel'

of the pedal's elastic resistance governs the 'strategy' of braking --

neither too abruptly nor too softly. Similar feedbacks influence the

automatized motions of the hands on the wheel, etc.

Other books

Sea Mistress by Candace McCarthy

Wild Child: A Skull Kings MC Novella by Sage L. Morgan

The Remnants of Yesterday by Anthony M. Strong

The Winning Summer by Marsha Hubler

Parched by Georgia Clark

Rough Waters by Nikki Godwin

Modern Arrangements: Complete Trilogy (Modern Arrangements #1-3) by Sadie Grubor

Burn for You by Stephanie Reid

Buffalo Before Breakfast by Mary Pope Osborne

Impossible by Komal Lewis