The Accountant's Story (32 page)

In Colombia on December 8 we light candles on the streets to celebrate the beginning of our Christmas holiday. I remember one time we lit more than one hundred of the candles we had made around the clinic. I could see a little bit and it was beautiful. Then we prayed. When I was in the clinic I continued my research on AIDS with the help of a bacteriologist, and Dr. Juan Carlos Tirado from the clinic, a man who became a friend. In the clinic everybody was very nice to me.

I always had hope that one day I would be free. The years passed by and my lawyers argued with the state and my family grew up. In the prison I had three more children, two girls and a boy. Meanwhile the flood of cocaine into America did not slow down, just different people got rich from it.

Pablo was never forgotten. Around the world his name grew in legend. In death he was the greatest criminal of history. In Colombia on the anniversary of his death thousands of people still march in a parade, then go to his cemetery to pray for his soul—and to give him honor. And our mother, until her death, slept each night with one of his shirts beneath her pillow. She was never ashamed to be his mother. As a baby he had told her, “Wait till I grow up, Mommy, I’m going to give you everything.”

But no one could have imagined the cost of making that promise come true.

I served my sentence. I thought about my brother often, but not too much about those days. It was not because of the pain those memories brought, but because it is always better to think about the future. When it was close to my time being served I was taken to the office of a judge who told me, “Mr. Escobar, you might be leaving soon. We need you to talk. We need you to start telling us which members of the government Pablo had paid to change the constitution to cancel extradition. We need to know which members of the army and the police were involved.”

During my term I had spoken with many different people. From New York the prosecutor of La Kika, Cheryl Pollack, came and we spoke. The DEA man on that case, Sam Trotman, came and we spoke. When possible I was able to answer their questions. But never did I mention a single name of the people who had helped my brother. I told this judge, “I can’t do that.”

The government offered me a house outside Colombia and protection for my family if I cooperated with them. “We will maintain your family,” they said.

When still I refused they promised me more consequences. I had spoken to the judge and DA and told him that I was not going to betray any of the many generals, colonels, judges, congressmen, or anybody from the government that had helped my brother or other members from the cartel of Medellín. The government was upset and one day before I was released a government official came to the hospital with two envelopes. The first one was opened and said I would be free the next day. After all those years I would be a free man once again. My mother was there and she kissed me.

The government man started crying. The second envelope was charges of kidnapping against me. Supposedly on August 18, 1991, I had detained a man who owed me money until it was paid. The penalty was between four and six more years.

My mother heard this charge and fell on the floor.

It was a lie. I had been in the Cathedral on that day. In addition, more than ten years had passed since the accused crime, longer than our statute of limitations. But still they brought the charges against me. I served four years more before my full trial on this charge. When these charges were read they were all about Pablo Escobar, Pablo Escobar, Pablo Escobar. Roberto Escobar is the brother of a criminal who committed terrorism, sold drugs, killed people, and committed other crimes.

I told the judge that they were supposed to judge me for who I am. I said, “I’m not here to pay for my brother’s crimes. I beg you, the law of Colombia, to judge me, Roberto Escobar, for the things that I did, but don’t judge me because I am the brother of Pablo Escobar.”

The prosecutor made them focus on the detainment and I presented my evidence to prove I wasn’t guilty. Finally in 2004 they had to allow me to leave the prison a free man. I had to pay large penalties of money and property to the state, but I was free. I was never accused of crimes of violence. In April of 2008 I received a notification from the prosecutor, which said they had made a mistake in holding me for all those years and I also received a $40,000 settlement for their error.

I am living on a farm now, like my father, with some cattle. I own some land. The days of the wars are long behind me. I don’t visit with many people from those days when Pablo seemed to own the world. There are still many people in prisons in my country and the United States who will stay there for the rest of their lives, but others like me have finished their sentences and have moved on.

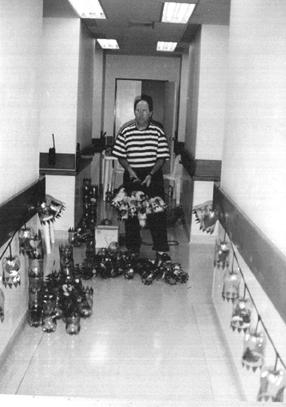

Not too much of Pablo’s possessions remain. I was able to get back from the judge some of Pablo’s possessions from the Cathedral, in addition to some of the racing bikes my company had made. I still ride, but close behind a car that I can just see in front of me. I also walk to stay in shape, and I don’t drink or smoke. I dedicate my time to my family. I still continue to work on my AIDS project, which has become a reality. I believe I have helped alleviate the suffering of a lot of patients and there is research being done based on my discovery.

I have never returned to Napoles. It is a shell, falling apart and lived in by the homeless. The roof has holes and there are rusted bodies of Pablo’s classic cars. People have come there and pulled apart everything for their use or for memories of Pablo. Only the rhinos have survived; the herd has grown much larger and they live near the river. Some of the rhinos have traveled more than three hundred kilometers upriver, and with those rhinos lives Pablo’s memory. They are too big to move, too dangerous, and the government does not know what to do about them.

And finally there is the money. It is impossible to even imagine how much money remains put away somewhere, probably never to be discovered. People who managed millions of dollars got killed without telling anyone where the money was hidden. Or they took the money and disappeared when Pablo was killed. I feel sure there are undiscovered coletas in houses all throughout Colombia—but also in New York and Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles, and the other cities in which Medellín did business. I am also certain there are bank accounts in countries whose numbers have been lost and forgotten and never will be opened again.

And there is money hidden and buried in the ground.

For me, it’s over. I still have the pains from the bomb and from my memories. I live quietly with the help I need. And also with the knowledge that whatever is thought about my brother, from the people who loved him to those filled with hate, he will live forever in history.

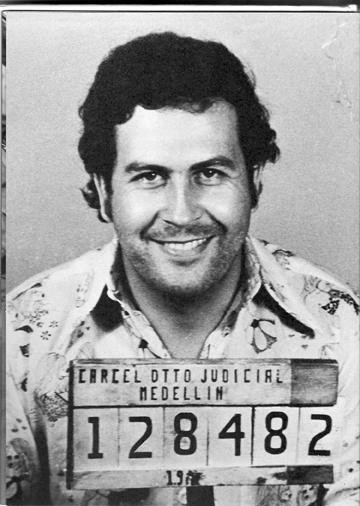

Pablo’s mug shot.

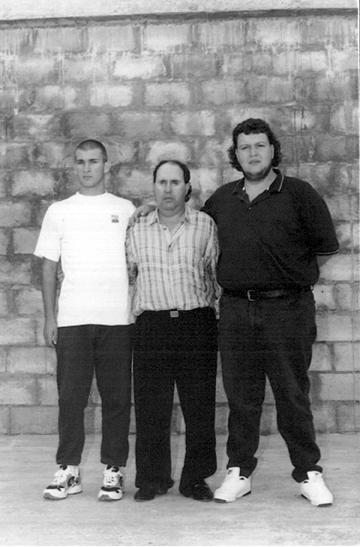

With my sons, Jose Roberto (left) and Nicholas, in a photo taken at the maximum security Itagui Prison in 1994.

Proposing a toast, sometime in the mid-1980s.

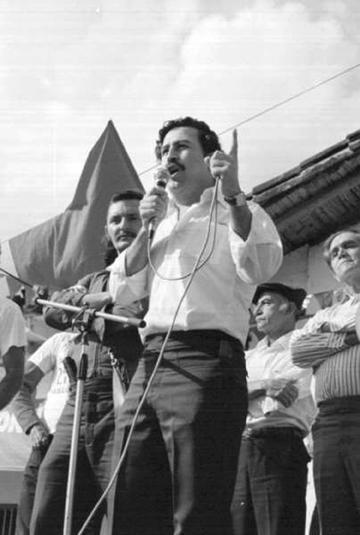

Pablo at his happiest, speaking to the people during a political campaign.

Unlike other politicians, when Pablo gave his word to the people, he kept it: He always brought in his people to supply or build exactly what he’d promised.

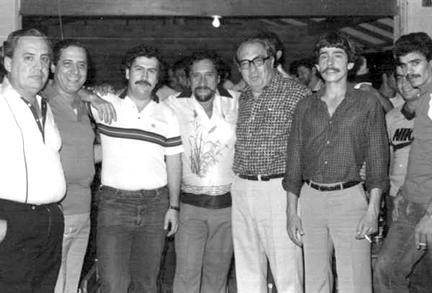

Pablo with some of our cousins.