The 30 Day MBA (48 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Igor Ansoff, while Professor of Industrial Administration in the Graduate School at Carnegie Mellon University, published his landmark book,

Corporate Strategy

(1965), where he explained a way of categorizing strategies as an aid to understanding the nature of the risks involved. He invited his students to consider growth options as a square matrix divided into four segments. The axes are labelled with products and services running along the âx' axis, starting with âpresent' and ânew'; and markets up the ây' axis similarly labelled (

Figure 12.3

).

FIGURE 12.3

Â

Ansoff's Growth Matrix

Ansoff then went on to assign titles to each type of strategy, in an ascending scale of risk (you can find out more about the matrix at

http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/worksheets/ AnsoffMatrixBusinessDownload.htm

):

- Market penetration, which involves selling more of your existing products and services to existing customers â the lowest-risk strategy.

- Product/service development, which involves creating extensions to your existing products or new products to sell to your existing customer base. This is more risky than market penetration, but less risky than entering a new market where you will face new competitors and may not understand the customers as well as you do your current ones.

- Market development involves entering new market segments or completely new markets either in your home country or abroad.

- Diversification is selling new products into new markets, the riskiest strategy as both are relative unknowns. Avoid, unless all other strategies have been exhausted. Diversification can be further subdivided into four categories of increasing risk profile:

- Horizontal diversification (entirely new product into current market).

- Vertical diversification (move backwards into firms supplier's or forward into customer's business).

- Concentric diversification (new product closely related to current products either in terms of technology or marketing presence but into a new market).

- Conglomerate diversification (completely new product into a new market).

- Horizontal diversification (entirely new product into current market).

Boston Matrix

Developed in 1969 by the Boston Consulting Group (see above), this tool can be used in conjunction with the life-cycle concept (see

Chapter 3

, Product/Service Life Cycle) to plan a portfolio of product/service offers. The thinking behind the matrix is that a company's products and services should be classified according to their cash generating or consumption ability against two dimensions: the market growth rate and the company's market share (

Figure 12.4

). Cash is used as the measure rather than profit, as that is the real resource used to invest in new offers. The objective then is to use the positive cash flow generated from âcash cows', usually mature products that no longer need heavy marketing support budgets, to invest in âstars', that is, fast-growing, usually newer products, positioned in markets in which the company already has a high market share â usually newer markets. âDogs' should be disinvested and âquestion marks' limited in number and watched carefully to see if they are more likely to become stars or dogs.

FIGURE 12.4

Â

The Boston Matrix

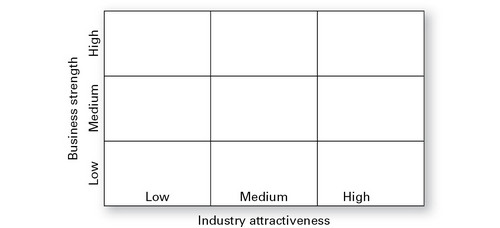

The GEâMcKinsey Directional Policy Matrix

General Electric was much taken by the visual aspect of the Boston Matrix and was using it to enhance its own performance using another consulting firm, McKinsey and Company, to help. Between them, in 1971 they came up with a variant and in some ways an improvement by substituting business strength and industry attractiveness for market share and market growth rate. The logic being that although these are subjective measures, they are more accessible than market growth and share, as these are hard to establish and in any event the figures are themselves largely subjective suppositions based largely on opinions (

Figure 12.5

).

FIGURE 12.5

Â

The GEâMcKinsey directional policy matrix

Other matrix variations

A dozen or so other similar matrices are in use, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. Arthur D Little Inc, a management consultancy founded in 1886, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, came up with its own matrix in the late 1970s, using competitive position and industry maturity as the directions. Two business school professors, Gary Hamel (London Business School) and C K Prahalad (University of Michigan), developed a matrix in 1994 as an aid in setting specific acquisition and deployment goals. Other academics, in the United States (Charles W Hofer and Dan Schendel) and in the UK (Cranfield colleagues Malcolm McDonald and Cliff Bowman) as well as companies such as Shell have all added twists to the basic matrix strategy tool.

Cipher Systems (

www.cipher-sys.com/analysis.html

), a US consultancy firm, provides a collection of strategic analysis tutorials on these and other matrices.

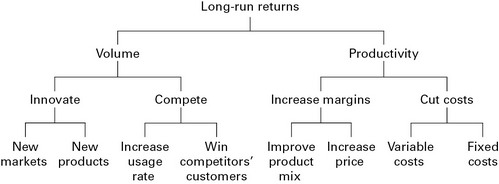

The long-run return pyramid

Another helpful strategy tool is the long-run return pyramid, which is in effect a checklist of growth options. None of the options are mutually exclusive and the tool does not provide for any form of evaluation. Nevertheless, it can be a valuable aide-mémoire to ensure that no stone has been left unturned during the strategic review process. The pyramid's pedigree is unknown, but it is loosely based on the DuPont's Return on Investment Pyramid, used to trace all the performance ratios that influenced return on investment. The pyramid in the form shown in

Figure 12.6

is attributed to Robert Brown, a senior academic at Cranfield School of Management.

FIGURE 12.6

Â

The long-run return pyramid

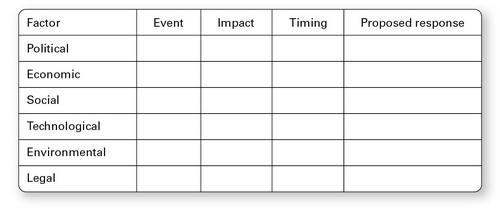

PEST (political, economic, social and technological)

This is a framework predating Porter's five forces approach that categorizes the external factors that influence strategy under headings such as political, economic, social and technological forces. Often two additional factors, environmental and legal, are added, changing the acronym to PESTEL analysis (

Figure 12.7

).

FIGURE 12.7

Â

PESTEL analysis framework

Two events on opposite sides of the globe provide a vivid illustration of the dimensions of environmental factors on business strategy. When Eyjafjallajokull, the Icelandic volcano, erupted in April 2010, air traffic around Europe and across the Atlantic ground to a halt for six days. Airlines lost up to half their annual profits, business passengers were stranded for days, and supply chains, shortened by just in time purchasing strategies, dried up. Now arguably there is little that business could do directly or immediately to mitigate these problems, but the experience served to demonstrate the interconnection of seemingly remote environmental factors and makes more obvious and immediate the reasons business have to take such issues as climate change seriously. Even if you are in no danger, unlike Lohachara, once island home to 10,000 people and the first inhabited island to be wiped off the face of the Earth by global warming in 2006, you will eventually be affected by an environmental issue.

Another environmental disaster occurred the following month when BP's Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico killing 11 people died and injuring 17. The ecological damage caused by the slick threatened some of the most important wildlife habitats. The cost to BP and its reputation are incalculable, but the stock market took a down payment by wiping £13 billion (US $19.9 billion; â¬15 billion) off its value in two weeks. BP has had to adjust its business strategy to incorporate expansion into the politically dangerous Russian market to compensate for its environmental disaster.

The environment as a business opportunity

Going green, for example, can represent an opportunity to use concerns about the environment as a lever to develop a strategy for growth. Whole new industries are being created to make solar, wind and wave power. Battery technology is being developed to run vehicles that can compete on range and speed with conventional ones. And sound environmental policies can produce both a successful growth strategy and immediate savings that drop to the bottom line.

Elective: Introduction to International Global Business

B

usinesses with a strong global presence have not had a better opportunity to prove their worth and resilience than during the recent worldwide economic downturn. BrandZ (

www.brandz.com

), a research company that studies global brands, has asked over 1.5 million consumers and professionals across 31 countries to compare over 50,000 brands each year since 2005. They rank the top 100 brands each year with such names as Google, Microsoft, McDonald's, IBM, Apple, Coca-Cola, BlackBerry, HBSC, Shell and Walmart regularly heading the list. Their 2012 study shows that the value of the BrandZ⢠Top 100 most valuable global brands grew 66 per cent between the first valuation in 2006 and 2012. During that six-year period, the BrandZ⢠portfolio of highly valued brands outperformed the S&P 500 by 103 per cent. It's no coincidence that these same companies are the largest recruiters of MBAs, according to

Fortune Magazine

's

annual review. Even Goldman Sachs, 78th in the global brands, and in the sector hit worst by economic turbulence, hires 100 MBAs each year. Google takes in so many MBAs it has a dedicated website (

www.google.com/jobs/mba

) as do Microsoft and Vodafone. Shell, unsurprisingly, is so committed to globalization it has formed a partnership with the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), one of the world's most respected business schools to provide scholarship to students from Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

All top business schools have International Business as the focus of their teaching and they strive hard to create an international flavour throughout. Wharton, for example, had 7,493 applications and only 862 accepted students. They claim to have 70 countries represented, with international students making up 37 per cent of the class.

Why business needs a global reach

The following two case studies illustrate two of the key advantages that businesses seek to gain by extending their operations to achieve global reach.

CASE STUDY

Â

McDonald's Corporation: Grow the customer base

McDonald's must be the archetypical international business. Its 13-strong board members, led by Andrew J McKenna, non-executive Chairman since April 2004, have global experience in companies of world repute such as Aon Corporation (the leading provider of risk management services, insurance and reinsurance), Procter & Gamble, Wells Fargo, NIKE, Inc, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc and Hershey. Unsurprisingly, given the fact that they are the world's biggest property company, they also have the non-executive Chairman of Jones Lang LaSalle, the world's biggest real estate services business which employs more than 30,000 people in 750 locations in 60 countries.

The business had an inauspicious start when brothers Richard and Maurice McDonald opened a single restaurant in San Bernardino, California in 1940. The brothers had been in the restaurant business albeit in a modest way since 1937, operating a hamburger stand near the Santa Anita racetrack. By 1948 the McDonald brothers were operating a small chain of carhop drive-ins, with waiting staff delivering food on skates direct to customer's cars, but with consumers becoming more price conscious they decided on a new business model. They set about streamlining the food production and delivery process with staff concentrating on single tasks. Three grillmen did nothing but flip burgers, while two did milkshakes and two made french fries. Other staff packed and served on the counter. The McDonald brothers had done for hamburgers what Henry Ford had done for cars by bringing mass production to the restaurant business.

The corporation's international expansion began in 1967, when the chain opened its first store outside the United States across the border in Canada. By the late 1970s, competition from other hamburger chains such as Burger King and Wendy's intensified and the so-called hamburger wars put such pressure on margins that McDonald's set about penetrating overseas markets with a vengeance. By 1991, 37 per cent of sales came from restaurants outside the United States. Today McDonald's have more than 32,400 restaurants in more than 100 countries, straddling every continent. Half of the corporation's business is still in the United States.

CASE STUDY

Â

IBM: Outsourcing globally

Outsourcing is the activity of contracting out the elements that are not considered core or central to the business. It is an important strategy open to a business that will help it limit the amount of cash it has to raise and utilize to function and so help it make a superior return on the funds invested. There are obvious advantages to outsourcing; the best people can do what they are best at. IBM, the world's second most valuable brand in 2012 after Apple uses global reach to maintain its resilience being a brand that pioneered the mainframe and has successfully adapted to the cloud age, while others have fallen by the

wayside. In 2008 IBM completed a major overhaul of its value chain and for the first time in its century-long history created an Integrated Supply Chain (ISC) â a centralized worldwide approach to deciding what to do itself, what to buy in and where to buy in from. Suppliers were halved from 66,000 to 33,000; support locations from 300 to three global centres, Bangalore, Budapest and Shanghai. Manufacturing sites reduced from 15 to nine, all âglobally enabled' in that they can make almost any of its products at each plant and deliver them anywhere in the world. In the process IBM has lowered operating costs by more than $4 billion a year.

International trade theory: an A to P

No self-respecting business graduate would settle for mere anecdotes or case examples, however relevant or convincing as an explanation of how international business came to be such a dominant feature of commercial life. These are the key aspects of the theories and limitations of those theories that underpin the subject of international trade, which an MBA needs at least a rudimentary appreciation of.

Absolute advantage

Adam Smith, the Scottish economist whose âInvisible Hand' saw all economic activity as being subject to the law of unintended consequences, also had a thing or two to say about Mercantilism (see below), the prevailing big idea on international trade. In 1776, in his blockbuster book

The Wealth of Nations

, Smith argued that for a country â and by extension the enterprises that make up that country â to simply try always to export more than they imported was both unrealistic and uneconomic. He argued that countries differed in their ability to produce goods efficiently and so had an inherent cost advantage.

Natural advantage

An industry that Smith drew on for his theory was the French wine trade, which due to good soil and a benign climate had the world's most efficient wine industry. Despite shifts in weather patterns, improvements in technology and sheer determination, England's wine industry some 240 years on is still dwarfed by that of France, which makes more and arguably better wine at a lower cost. Other countries, particularly those in the New World â Argentina, Australia, Chile and the United States in particular have muscled in on the trade, but those countries too shared France's natural advantage, but in some cases with the added twist of lower costs of either land, labour or both.

Acquired advantage

The French wine industry in Smith's day also had generations of experience in the manufacturing process. This accumulated expertise gave them an acquired advantage. At this time England had the most efficient textile manufacturing industry in the world, courtesy of such innovations as Richard Arkwright's water frame, James Hargreaves's Spinning Jenny, and Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule (the Spinning Jenny and Water Frame combined,

patented in 1769). James Watt's steam engine patented in 1775, allowed efficient semi-automated factories to operate in places where waterpower was not available so serving to increase England's acquired advantage in both textiles and other manufactured products.

A more recent example is that of Lean Manufacturing, an approach ascribed to Japanese companies such as Toyota, where they seek to eliminate or continuously reduce waste â that is, anything that doesn't add value. They use such headings as:

- Transport: keep process close to each other to minimize movement.

- Inventory: carrying high inventory levels costs money and if too low, orders can be lost.

- âJust in Time' (JIT) manufacturing should be aimed for.

- Motion: improve workplace ergonomics so as to maximize labour productivity.

- Waiting: aim for a smooth even flow so that men and machines are working optimally, reducing down time to a minimum.

- Defects: aim for zero defects as that directly reduces the amount of waste.

As a result of this approach many industries in Japan achieved an acquired advantage over those in other countries allowing them to dominate industries such as motor manufacturing and even to be able to export steel despite having to import iron and coal, its main ingredients.

Comparative advantage

David Ricardo, an English economist, member of Parliament, businessman, financier and speculator, in his 1817 book,

The Principles of Political Economy

, extrapolated Smith's theory to see what might happen if, as it looked might happen as the industrial revolution developed, one country â England in this case â had an absolute advantage in the production of all goods. Ricardo's conclusion was that a country should concentrate its efforts on those goods it produces most efficiently and be prepared to import goods from other countries even if it could make them more efficiently itself.

Most students and nearly all business managers find this argument counterintuitive but this example explains the principle. Would a world-class forensic accountant commanding fees of $5,000 a day to unravel the financial mess left behind at Lehman Brothers, who coincidentally is a great bookkeeper, be better off keeping their own books? As even the world's best bookkeeper would be pushed to make $500 a day, clearly a forensic accountant would be better off paying out for a bookkeeper and finding a few more firms like Lehman's to work on.

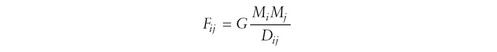

Gravity Model

The Gravity Model, first used by Jan Tinbergen, the Dutch economist and co-winner of the first Nobel prize in economics in 1969, postulates that just as Newton's law of gravity draws on distance and physical size between two objects to predict behaviour, trade between countries will be similarly influenced. His theoretical model, developed in 1952, states that the trade between two countries (i and j) takes the form of:

Where F is the trade flow, M is the economic mass (GDP) of each country, D is the distance and G is a constant. The mode appears to be empirically reliable and is used by such bodies as the World Trade Organization (WTO) to test the effectiveness of trade agreements. McDonald's' choice of Canada as its jumping off point for international growth supports the distance element of this formula and, though not quite in the same economic league, it is the 11th richest country in the world.

The HeckscherâOhlin model

Ricardo (See Comparative advantage) believed that advantage accrued to countries with greater labour productivity. Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin of the Stockholm School of Economics, extrapolated this idea by determining that countries are endowed with different factors such as capital, land and labour and it is those that collectively determine cost differences and hence advantage. The HeckscherâOhlin model (HâO model), as it became known, essentially says that countries will export products that make use of their plentiful and cheap factors of production and import products that use the country's scarce factors. This theory passes the common sense test easily. France, Ireland and the United States are all substantial exporters of agricultural products as they have a relatively high land density (acres per person), while China and South Korea have the advantage when it comes to goods that require an abundance of low-cost labour, such as clothing and footwear. In this latter area China's exports were so high as to attract trade barriers from the EU.

The Leontief Paradox

Economists like the HeckscherâOhlin model as it mirrors their ideas on how advantage should work in theory. Unfortunately the HâO model is unreliable at predicting trade patterns, less so than the less elegant proposition advanced by Ricardo's comparative advantage (see above). Wassily

Leontief, a Russian economist, son of a Professor of Economics and a Nobel Prize winner, demonstrated the limitations of the HâO model by showing that since the United States was awash with capital compared to most other countries, with the most sophisticated venture capital and stock markets in the world, they should, in theory, be a major exporter of capital intensive goods and an importer of labour intensive goods. Using the 1947 importâexport tables covering 200 US industries Leontief showed the reverse to be the case. He postulated that demand and the availability of natural resources may play a greater role than supply in such cases and as is usual with academics called for more research to be carried out.