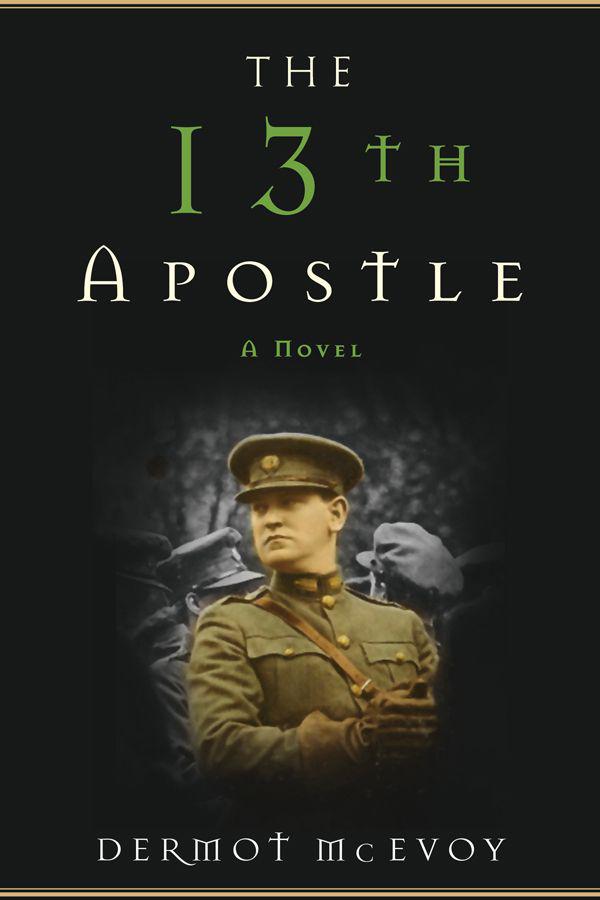

The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising

Read The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising Online

Authors: Dermot McEvoy

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #World Literature, #Historical Fiction, #Irish

This book is dedicated to five extraordinary writers from the old Lion’s Head saloon on Christopher Street in New York City—Joe Flaherty, David Markson, Lanford Wilson, Frank McCourt, and Pete Hamill.

Thank you.

Copyright © Dermot McEvoy 2014

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse

®

and Skyhorse Publishing

®

are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

®

, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-923-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-162636-561-2

Printed in the United States of America

C

ONTENTS

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I

want to thank all my Dublin cousins for their help in the writing of this book, as their knowledge of the city was invaluable: Maura and Gerry Bartley and their sons, Declan, Father Kevin, and Brendan; Terry O’Neill and his wife, Mary; and Monsignor Vincent Bartley on this side of the Atlantic.

I want to especially thank Collins’s biographer, Chrissy Osborne, and her husband, David. I don’t think anyone knows more about Michael Collins’s Dublin than Chrissy. Her books opened new doors to me, and there’s nothing more exciting than traveling with Chrissy to the houses Collins used around Dublin town to get a feel of what it must have been like to be a wary rebel in Dublin during the War of Independence.

A big thank-you to

Irish Independent

columnist Mary Kenny for her generous help on the Collins-Churchill friendship, which she portrayed so brilliantly in her play

Allegiance

, and for introducing me to the seduction of Black Velvet—Guinness and champagne—at the Horseshoe Bar in the Shelbourne Hotel in Dublin.

One of the characters in the book, Charlie Conway, was my great-uncle. I want to thank Seán Connolly of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association for finding Uncle Charlie’s military records. I also want to thank Eibhlin Roche of the Guinness Archive, who was most helpful in obtaining Charlie’s employment record at the brewery between 1902 and 1932. Their work breathed new life into Charlie, at least as a fictional character.

Thanks to my hardworking editor, Jenn McCartney, and publisher, Tony Lyons, who have always encouraged me in my insanely quixotic writing quests.

Special thanks to Rosemary Mahoney and Mike Coffey for their editorial suggestions.

And a heroic thank-you to the only two people who read the book as I wrote it: Marianne Fagan and Jack Hornor. Their suggestions and encouragement made my complicated task easier.

“You will not get anything from the British government unless you approach them with a bullock’s tail in one hand and a landlord’s head in the other.”

—Michael Collins

Ballinalee, County Longford

October 7, 1917

A

UTHOR

’

S

N

OTE

F

or seven hundred years the British occupied Ireland, stealing its land, looting its meager wealth, enacting extraordinarily punitive taxes, and imposing a famine on its inhabitants.

On Easter Monday, April 24, 1916, a handful of rebels commandeered buildings around Dublin City and fought the British army to a standstill for nearly a week.

Almost immediately after their surrender, fourteen of the leaders were shot in the breaker’s yard of Kilmainham Gaol. Sixteen men in all were executed for their uprising against the British.

With the elimination of the 1916 leaders, another generation of revolutionaries rose to take their place.

This cadre was led by Eamon de Valera, a senior commandant who escaped execution because of his natural-born American citizenship, and Michael Collins, who would soon rise to hold the positions of Minister for Finance in the first

Dáil

and Director of Intelligence for the Irish Republican Army.

Collins’s reign as a revolutionary was short—a lively six years, between the Easter Rising and his death in an ambush on August 22, 1922.

But during that short period of time, he led a bloody guerrilla war that is now textbook for all emerging revolutionaries, much studied by the likes of Mao Tse-Tung and Yitzhak Shamir, who would later become the seventh prime minister of Israel. (Shamir’s

nom-de-guerre

, interestingly enough, was “Michael.”) For the first time, the British became the hunted—and they did not like it. Michael Collins, against impossible odds, had beat the British at their own game of intimidation.

One of Collins’s cohorts and co-conspirators was a fourteen-year-old Dublin boy he met in the General Post Office during Easter Week.

His name was Eoin Kavanagh.

This is their story.

Dermot McEvoy, Jersey City, New Jersey, 2014

“And David put his hand in his bag, and took thence a stone, and slang it, and smote the Philistine in his forehead; and the stone sank into his forehead, and he fell upon his face to the earth.”

—1 Samuel 17:49

OCTOBER 2006

1

“

J

ohnny Three,” an ancient, gravelly voice said. “It’s time to come get me. Now.” Then the phone went dead.

Eoin Kavanagh III—known as Johnny Three to everyone—knew it was his grandfather’s way of summoning him back to Dublin for the final farewell. “I have to go to Dublin,” Kavanagh said to his wife, Diane. “I think I should go alone.”

“I’m coming,” his wife said, and Kavanagh was smart enough not to argue this time.

When the flight from New York landed, they headed to the old man’s house in Dalkey. “I don’t like this,” Johnny Three remarked to his wife as their taxi swung to the southside of Dublin Bay.

“Why?”

“It’s October 16th.”

“So?”

“Michael Collins’s birthday,” replied Johnny. “You know the old man.”

“He’s picked his death day,” Diane exclaimed, shocked.

“Yes, he has.”

When they arrived at the house, Bridie, his grandfather’s longtime housekeeper, opened the door. “I shouldn’t have,” she said, then repeated, “I shouldn’t have.”

“Are you alright, Bridie?” asked Johnny Three as Diane took the distraught woman by the arm.

Johnny Three heard a ruckus from the bedroom above. He knew that his grandfather, the original Eoin Kavanagh, would not go out quietly. “Bless my ancient HOLE,” he heard his grandfather say.

“I shouldn’t have called the priest,” said Bridie as a curate, purple stole flying about him, came running down the stairs.

“He’s incorrigible,” the harassed man said as he removed the stole and kissed the cross on the back.

“Thank you, Father,” said Bridie.

“Incorrigible,” said the priest to Johnny and Diane.

“Contrary,” corrected the grandson.

“Whatever!” the priest said as he exited the house.

Johnny chuckled at the priest’s distress and hit the stairs, followed by his wife. “How are you, grandpa?”

The old man looked up, and his eyes brightened as he surveyed his only grandchild. “Not good,” he said, motioning the couple toward his bed, which had a panoramic view of Dublin Bay and Dalkey Island.

The younger Kavanagh reached down and kissed his grandfather on the forehead. “Did you make your peace, grandpa?” he said.

“Peace my arse,” said Eoin. “Bloody priests never change.” The grandfather shooed his grandson away and motioned for Diane to come to him. “How are you, dear?” he said as he kissed her hand and then patted her gently on her round Presbyterian rump.

“Oh, grandpa,” she said and started to cry.

“There, there,” he said and patted her bottom again as he looked at his grandson and smiled. Johnny Three turned away so his wife wouldn’t see

him

smile. Death was banging on the door, but the old rebel kept petting Diane’s caboose.

The old man was crazy about Diane Kavanagh. Even after bearing three children, she was still a remarkably beautiful and fit woman. She had gorgeous brown hair, dancing blue eyes, and one of the most remarkable bottoms God had ever created. “How did an eejit like you end up with a woman of that caliber?” he liked to chide his grandson.

“She fell in love with you,” he replied with some truth, “but she married me.”

“Grandpa.”

“Yes, son.”

“Should I follow your wishes?”

“Yes,” said Eoin. “To the letter.” He looked intently at his grandson. “I have a surprise for you.”

“You’re leaving me the house?”

“Who else would I leave it to? You’re the last

real

Kavanagh.”

“How about the Church or the State?” A negative smile gave the answer. “What’s the surprise?”

“You’ll see.” With that, the old man serenely laid his head on the pillow and closed his eyes.

“Is he?” asked Diane with concern.

Johnny Three was a little more cynical. “I wouldn’t bet on it,” he said.

Suddenly Eoin’s eyes shot open, and he urgently motioned the grandson to his side.

“Yes, grandpa.”

“Fook,” he said, suddenly having trouble forming words.

“Fuck?” repeated Johnny.

“Fook Eddie de Valera.”

The old man was defiant to the end. Then, by a blink of his eyes, he asked his grandson to come closer. “How did he do it?” he said in a whisper.

“Who?” said Johnny.

“How the fook did Mick Collins pull it off?”

“I don’t know, grandpa.”

“Neither do I, son.” A single tear rolled down Eoin Kavanagh’s cheek. “My God, I loved that man.” His eyes slowly closed.

“Oh, Johnny, he’s gone.” Johnny took his wife in his arms and hugged her as hard as he could. “He’s gone,” she said again. With that, Diane heard the loudest laugh she had heard in a long time. Johnny Three was doubled over. “What are you doing?”

“I’m giving the old man,” he said, catching his breath, “the sendoff he deserves.”

EOIN KAVANAGH, TD, DEAD AT 105

WAS LAST SURVIVING GPO REBEL

Johnny Three read the

Irish Times

headline and smiled. He handed it back to the army officer the

Taoiseach

, the Irish prime minister, had sent over to set up the viewing in the rotunda of Dublin’s City Hall.

Eoin Kavanagh lay in a simple box. He was dressed in his Volunteer’s uniform. The man hadn’t gained a pound since 1916.

“Can I have a moment alone?” Johnny asked the officer. He straightened the tricolor on the bottom half of the coffin and looked at his grandfather. The old man still wore a beard, and his head of Paul O’Dwyer-esque white hair—the closest thing to an Irish halo—was still full. He had insisted on being viewed in the City Hall because that was where his boss, Michael Collins, had lain in state after he was killed in 1922. You couldn’t mention the name of Eoin Kavanagh without people saying that he was The Big Fellow’s personal bodyguard—or perhaps something more. Sometimes, with an unsettling gleam in his eye, Eoin would refer to himself as “Mick’s Thirteenth Apostle,” never elaborating. The old man knew his place in history, and even in death, he wanted to be sure he got all he had coming to him—right down to the twenty-one gun salute at Glasnevin, where he would be buried in the army cemetery, right next to General Collins.

“I think I need a drink,” said Kavanagh to the officer. “I’ll be back in a while.” Johnny went down the front steps of the City Hall into Cork Hill. He swung into Palace Street at one of the Dublin Castle side gates and headed down Dame Lane, which would take him across South Great Georges Street and into Dame Court. He and the old man had walked this narrow street many times as Eoin told him how he and Collins would often case English touts to the gates of the Castle itself, then retreat to the Stag’s Head for a drink.

At night, the Stag’s Head was a madhouse, but, in the daytime, it was serene—one of the most beautiful Victorian pubs in Dublin. Johnny Three was first brought there by his grandfather during his summer visits in the late 1960s and ’70s.

The death of Jack Kennedy had taken a lot out of the old man—for a while. It was like losing Collins again. Eoin Kavanagh was the only member of Congress to travel with Kennedy on his trip to Ireland in 1963. They had sat with the

Taoiseach

, Seán Lemass, and regaled Kennedy with stories of 1916, the War of Independence, and being Michael Collins’s personal bodyguard. Although Kavanagh and Jack Lemass had been on opposite sides in the Irish Civil War, they had remained friends, even after Kavanagh left Ireland in 1922 and went to America. During World War II, Congressman Kavanagh served as Lemass’s personal intermediary with Eoin’s long-time friend, Franklin Roosevelt, during Ireland’s “Emergency.” Kennedy had marveled at the close relationship between Lemass and Kavanagh and noticed that the Congressman never uttered a word to President de Valera, Lemass’s mentor, who was sitting on the same dais. It brought a smile to Kennedy’s face—he knew all about the Irish and their grudges.

After Kennedy died, Lemass had phoned. “Come back to Ireland,” he told his old friend. And he did: Kavanagh ran for the

Dáil

as an independent in the South Dublin district he had been born in and ended up sitting in the opposition aisle to his friend, the

Taoiseach

. “You’re nothing but a troublemaker,” Lemass laughed after Eoin Kavanagh was sworn in as a

Teachtaí Dála

(TD): Deputy to the

Dáil

, the Irish parliament.

“Jack,” Kavanagh deadpanned, “how could you t’ink such a thing?” (Eoin had known Lemass even before he Gaelicized his first name, for political reasons, to Seán. To Eoin, he would always be plain old Jack.)

And a troublemaker he was. In 1971, after Lemass died, Deputy Kavanagh began running guns to the North after internment without trial was instituted by the British government. When Liam Cosgrave became

Taoiseach

in 1974, he was indicted. He refused to resign his seat in

Dáil Éireann

and stood trial, where he proudly declared his guilt—and was found innocent by a jury of his delighted peers. “This is a great day for Ireland,” Kavanagh declared on the steps of the Four Courts, where he and his wife of fifty-two years stood before the assembled media, “and a bad day for Liam Cosgrave and those other

Fine Gail

eunuchs who are trying to turn the Irish government into the subservants of the British imperialists! What a bunch of pussies! Mick Collins would be appalled!” When infuriated, the New Yorker in Eoin Kavanagh had a tendency to surface with a bang. Mrs. Kavanagh looked straight into the gutter, hoping her feminist friends back in New York would not see the smile on her face.

Johnny Three had been with him when he crossed paths with Eamon de Valera for the last time. It was at a function at the Gresham Hotel in O’Connell Street in June 1975, just months before Dev’s death. The two old antagonists had literally bumped into each other at the reception. De Valera, blind as a bat, was as sharp as ever. “Eoin Kavanagh,” he said, looking down at the diminutive Kavanagh, “I see young, respectable Cosgrave doesn’t like you.” Dev had had his own run-ins with the father, W.T. Cosgrave, during the Civil War.

“Well, Chief,” said Eoin, “neither did his old man!”

De Valera laughed, enjoying his first conversation with Kavanagh since 1922. “God be with you, Eoin Kavanagh.”

De Valera wasn’t going to get off that easy. “Chief,” Eoin said.

“Yes.”

“Mick was right.”

De Valera looked down with unseeing eyes through his thick glasses and sighed. “Perhaps,” he responded. “Perhaps.”

“God bless, Chief,” were the last words Eoin Kavanagh said to his former antagonist.

De Valera slowly moved through the room on his way out. “Look,” said Eoin to Johnny Three. De Valera had extended his supine hands to the side, like the Blessed Virgin Mary, so people could touch him. “Look at that old bastard work the room!” said Eoin with genuine admiration. “Goddamn it, Johnny, Jack Kennedy couldn’t have done it better.” Eoin Kavanagh appreciated political talent when he saw it.