The 12th Planet (20 page)

Authors: Zecharia Sitchin

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

Fig. 53

Fig. 54

As brother of Sin and uncle of Utu and Inanna, Adad appears to have felt more at home with them than at his own house. The Sumerian texts constantly grouped the four together. The ceremonies connected with the visit of Anu to Uruk also spoke of the four as a group. One text, describing the entrance to the court of Anu, states that the throne room was reached through "the gate of Sin, Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar:' Another text, first published by V. K. Shileiko (Russian Academy of the History of Material Cultures) poetically described the four as retiring for the night together.

The greatest affinity seems to have existed between Adad and Ishtar, and the two were even depicted next to each other, as on this relief showing an Assyrian ruler being blessed by Adad (holding the ring and lightning) and by Ishtar, holding her bow. (The third deity is too mutilated to be identified.) (Fig. 55)

Was there more to this "affinity" than a platonic relationship, especially in view of Ishtar's "record"? It is noteworthy that in the biblical Song of Songs, the playful girl calls her lover

dod-a

word that means both "lover" and "uncle." Now, was Ishkur called Adad—a derivative from the Sumerian DA.DA—because he was the uncle who was the lover?

But Ishkur was not only a playboy; he was a mighty god, endowed by his father Enlil with the powers and prerogatives of a storm god. As such he was revered as the

H

urrian/Hittite Teshub and the Urartian Teshubu ("wind blower"), the Amorite Ramanu ("thunderer"), the Canaanite Ragimu ("caster of hailstones"), the Indo-European Buriash ("light maker"), the Semitic Meir ("he who lights up" the skies). (Fig. 56)

A god list kept at the British Museum, as shown by Hans Schlobies

(Der Akkadische Wettergott in Mesopotamien),

clarifies that Ishkur was indeed the divine lord in lands far from Sumer and Akkad. As Sumerian texts reveal, this was no accident. Enlil, it seems, willfully dispatched his young son to become the "Resident Deity" in the mountain lands north and west of Mesopotamia.

Why did Enlil dispatch his youngest and beloved son away from Nippur?

Several Sumerian epic tales have been found about the arguments and even bloody struggles among the younger gods. Many cylinder seals depict scenes of god battling god (Fig. 57); it would seem that the original rivalry between Enki and Enlil was carried on and intensified between their sons, with brother sometimes turning against brother—a divine tale of Cain and Abel. Some of these battles were against a deity identified as Kur—in all probability, Ishkur/Adad. This may well explain why Enlil deemed it advisable to grant his younger son a far-off domain, to keep him out of the dangerous battles for the succession.

Fig. 55

Fig. 56

Fig. 57

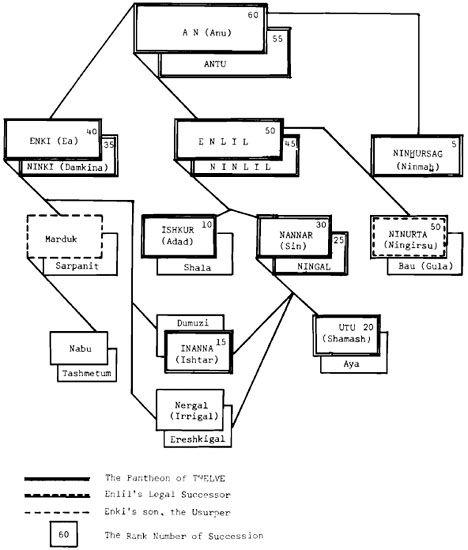

The position of the sons of Anu, Enlil, and Enki, and of their offspring, in the dynastic lineage emerges clearly through a unique Sumerian device: the allocation of

numerical rank

to certain gods. The discovery of this system also brings out the membership in the Great Circle of Gods of Heaven and Earth when Sumerian civilization blossomed. We shall find that this Supreme Pantheon was made up of

twelve

deities.

The first hint that a cryptographic number system was applied to the Great Gods came with the discovery that the names of the gods Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar were sometimes substituted in the texts

by

the numbers 30, 20, and 15, respectively. The highest unit of the Sumerian sexagesimal system—60—was assigned to Anu; Enlil "was" 50; Enki, 40; and Adad, 10. The number 10 and its six multiples within the prime number 60 were thus assigned to

male

deities, and it would appear plausible that the numbers ending with 5 were assigned to the female deities. From this, the following cryptographic table emerges:

| | Male | Female |

| | | |

| | 60—Anu | 55—Antu |

| | 50—Enlil | 45—Ninlil |

| | 40—Ea/Enki | 35—Ninki |

| | 30—Nanna/Sin | 25—Ningal |

| 20—Utu/Shamash | 15—Inanna/Ishtar | |

| | 10—Ishkur/Adad | 5—Nin h ursag |

| | | |

| | 6 male deities | 6 female deities |

Ninurta, we should not be surprised to learn, was assigned the number 50, like his father. In other words, his dynastic rank was conveyed in a cryptographic message: If Enlil goes, you, Ninurta, step into his shoes; but until then, you are not one of the Twelve, for the rank of "50" is occupied.

Nor should we be surprised to learn that when Marduk usurped the Enlilship, he insisted that the gods bestow on him "the

fifty

names" to signify that the rank of "50" had become his.

There were many other gods in Sumer—children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews of the Great Gods; there were also several hundred rank-and-file gods, called Anunnaki, who were assigned (one may say) "general duties." But only

twelve

made the Great Circle. They, their family relationships, and, above all, the line of dynastic succession can better be referred to if we show them in a chart:

5

•

THE NEFILIM: PEOPLE OF THE FIERY ROCKETS

Sumerian and Akkadian texts leave no doubt that the peoples of the ancient Near East were certain that the Gods of Heaven and Earth were able to rise from Earth and ascend into the heavens, as well as roam Earth's skies at will.

In a text dealing with the rape of Inanna/Ishtar by an unidentified person, he justifies his deed thus:

One day my Queen,

After crossing heaven, crossing earth–

Inanna,

After crossing heaven, crossing earth–

After crossing Elam and Shubur,

After crossing...

The hierodule approached weary, fell asleep.

I saw her from the edge of my garden;

Kissed her, copulated with her.

Inanna, here described as roaming the heavens over many lands that lie far apart—feats possible only by

flying

—

herself

spoke on another occasion of her flying. In a text which S. Langdon (in

Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archeologie Orientale)

named "A Classical Liturgy to Innini," the goddess laments her expulsion from her city. Acting on the instructions of Enlil, an emissary, who "brought to me the word of Heaven," entered her throne room, "his unwashed hands put on me," and, after other indignities,

Me, from my temple,

they caused to fly;

A Queen am I whom, from my city,

like a bird they caused to fly.

Such a capability, by Inanna as well as the other major gods, was often indicated by the ancient artists by depicting the godsâ€"anthropomorphic in all other respects, as we have seen-with wings. The wings, as can be seen from numerous depictions, were not part of the body-not natural wings—but rather a decorative attachment to the god's clothing. (Fig. 58)

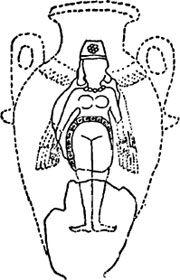

Inanna/Ishtar, whose far-flung travels are mentioned in many ancient texts, commuted between her initial distant domain in Aratta and her coveted abode in Uruk. She called upon Enki in Eridu and Enlil in Nippur, and visited her brother Utu at his headquarters in Sippar. But her most celebrated journey was to the Lower World, the domain of her sister Ereshkigal. The journey was the subject not only of epic tales but also of artistic depictions on cylinder seals—the latter showing the goddess with wings, to stress the fact that she flew over from Sumer to the Lower World. (Fig. 59)

Fig. 58

Fig. 59

The texts dealing with this hazardous journey describe how Inanna very meticulously put on herself seven objects prior to the start of the voyage, and how she had to give them up as she passed through the seven gates leading to her sister's abode. Seven such objects are also mentioned in other texts dealing with Inanna's skyborne travels:

- The SHU.GAR.RA she put on her head.

- "Measuring pendants," on her ears.

- Chains of small blue stones, around her neck.

- Twin "stones," on her shoulders.

- A golden cylinder, in her hands.

- Straps, clasping her breast.

- The PALA garment, clothed around her body.

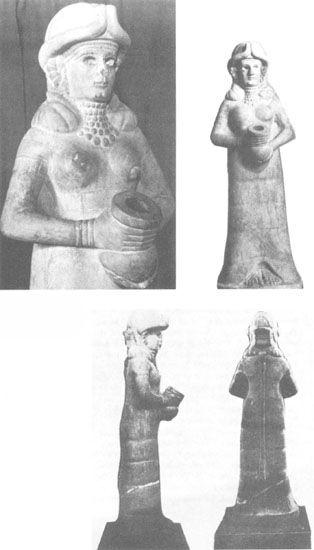

Though no one has as yet been able to explain the nature and significance of these seven objects, we feel that the answer has long been available. Excavating the Assyrian capital Assur from 1903 to 1914, Walter Andrae and his colleagues found in the Temple of Ishtar a battered statue of the goddess showing her with various "contraptions" attached to her chest and back. In 1934 archaeologists excavating at Mari came upon a similar but intact statue buried in the ground. It was a life-size likeness of a beautiful woman. Her unusual headdress was adorned with a pair of horns, indicating that she was a goddess. Standing around the 4,000-year-old statue, the archaeologists were thrilled by her lifelike appearance (in a snapshar, one can hardly distinguish between the statue and the living men). They named her

The Goddess with a Vase

because she was holding a cylindrical object. (Fig. 60)

Unlike the flat carvings or bas-reliefs, this life-size, three-dimensional representation of the goddess reveals interesting features about her attire. On her head she wears not a milliner's chapeau but a special helmet; protruding from it on both sides and fitted over the ears are objects that remind one of a pilot's earphones. On her neck and upper chest the goddess wears a necklace of many small (and probably precious) stones; in her hands she holds a cylindrical object which appears too thick and heavy to be a vase for holding water.

Fig. 60

Over a blouse of see-through material, two parallel straps run across her chest, leading back to and holding in place an unusual box of rectangular shape. The box is held tight against the back of the goddess's neck and is firmly attached to the helmet with a horizontal strap. Whatever the box held inside must have been heavy, for the contraption is further supported by two large shoulder pads. The weight of the box is increased by a hose that is connected to its base by a circular clasp. The complete package of instruments—for this is what they undoubtedly were—is held in place with the aid of the two sets of straps that crisscross the goddess's back and chest.

The parallel between the seven objects required by Inanna for her aerial journeys and the dress and objects worn by the statue from Mari (and probably also the mutilated one found at Ishtar's temple in Ashur) is easily proved. We see the "measuring pendants"—the earphones—on her ears; the rows or "chains" of small stones around her neck; the "twin stones"—the two shoulder pads-on her shoulders; the "golden cylinder" in her hands, and the clasping straps that crisscross her breast. She is indeed clothed in a "PALA garment" ("ruler's garment"), and on her head she wears the SHU.GAR.RA helmet—a term that literally means "that which makes go far into universe."

All this suggests to us that the attire of Inanna was that of an aeronaut or an astronaut.

The Old Testament called the "angels" of the Lord

malachim

—literally, "emissaries," who carried divine messages and carried out divine commands. As so many instances reveal, they were divine airmen: Jacob saw them going up a sky ladder, Hagar (Abraham's concubine) was addressed by them from the sky, and it was they who brought about the aerial destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The biblical account of the events preceding the destruction of the two sinful cities illustrates the fact that these emissaries were, on the one hand, anthropomorphic in all respects, and, on the other hand, they could be identified as "angels" as soon as they were observed. We learn that their appearance was sudden. Abraham "raised his eyes and, lo and behold, there were three

men

standing by him." Bowing and calling them "My Lords," he pleaded with them, "Do not pass

over

thy servant," and prevailed on them to wash their feet, rest, and eat.

Having done as Abraham had requested, two of the angels (the third "man" turned out to be the Lord himself) then proceeded to Sodom. Lot, the nephew of Abraham, "was sitting at the gate of Sodom; and when he saw them he rose up to meet them and bowed to the ground, and said: If it pleases my Lords, pray come to the house of thy servant and wash your feet and sleep overnight." Then "he made for them a feast, and they ate." When the news of the arrival of the two spread in the town, "all the town's people, young and old, surrounded the house, and called out to Lot and said: Where are the

men

who came this night unto thee?"

How were these men—who ate, drank, slept, and washed their tired feet—nevertheless so instantly recognizable as angels of the Lord? The only plausible explanation is that what they wore—their helmets or uniforms—or what they carried—their weapons—made them immediately recognizable. That they carried distinctive weapons is certainly a possibility: The two "men" at Sodom, about to be lynched by the crowd, "smote the people at the entrance of the house with blindness ... and they were unable to find the doorway." And another angel, this time appearing to Gideon, as he was chosen to be a Judge in Israel, gave him a divine sign by touching a rock with his baton, whereupon a fire jumped out of the rock.

The team headed by Andrae found yet another unusual depiction of Ishtar at her temple in Ashur. More a wall sculpture than the usual relief, it showed the goddess with a tight-fitting decorated helmet with the "earphones" extended as though they had their own flat antennas, and wearing very distinct goggles that were part of the helmet. (Fig. 61)

Needless to say, any man seeing a person—male or female—so clad, would at once realize that he is encountering a divine aeronaut.

Clay figurines found at Sumerian sites and believed to be some 5,500 years old may well be crude representations of such

malachim

holding wandlike weapons. In one instance the face is seen through a helmet's visor. In the other instance, the "emissary" wears the distinct divine conical headdress and a uniform studded with circular objects of unknown function. (Figs. 62, 63)

The eye slots or "goggles" of the figurines are a most interesting feature because the Near East in the fourth millennium

B.C.

was literally swamped with wafer-like figurines that depicted in a stylized manner the upper part of the deities, exaggerating their most prominent feature: a conical helmet with elliptical visors or goggles. (Fig. 64) A hoard of such figurines was found at Tell Brak, a prehistoric site on the Khabur River, the river on whose banks Ezekiel saw the divine chariot millennia later.

It is undoubtedly no mere coincidence that the Hittites, linked to Sumer and Akkad via the Khabur area, adopted as their written sign for "gods" the symbol , clearly borrowed from the "eye" figurines. It is also no wonder that this symbol or hieroglyph for "divine being," expressed in artistic styles, came to dominate the art not only of Asia Minor but also of the early Greeks during the Minoan and Mycenaean periods. (Fig. 65)

, clearly borrowed from the "eye" figurines. It is also no wonder that this symbol or hieroglyph for "divine being," expressed in artistic styles, came to dominate the art not only of Asia Minor but also of the early Greeks during the Minoan and Mycenaean periods. (Fig. 65)