Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (14 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

10.53Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Williams, who often complained of feeling like a ghost, had himself become a denizen of the night. The night eroticized his sense of absence, that oppressive emptiness he had carried with him since childhood. “Evening is the normal adult’s time for home—the family,” he observed in his diary in 1942, already aligning himself with the sexual renegades. “For us it is the time to search for something to satisfy that empty space that home fills in the normal adult’s life. It isn’t so bad, really. Usually we go home with nothing. Now and then we succeed.” Cruising was some dream-like odyssey of reclamation, as Tom says in

The Glass Menagerie

, “to find in motion what was lost in space.” A large part of its addictive thrill was in being chosen; it gave an emotional lift to Williams’s deflated self. He began to see sex as “spiritual champagne,” and the Rx for his blues.

The Glass Menagerie

, “to find in motion what was lost in space.” A large part of its addictive thrill was in being chosen; it gave an emotional lift to Williams’s deflated self. He began to see sex as “spiritual champagne,” and the Rx for his blues.

The excitement of pickups—“the asking look in his eyes”—turned tables on his hunger. (“

You

coming toward me—

please

make

haste!

. . . (You—you—is

this

you?—‘Coming toward me?’)”) By being desired, Williams was emptied of need; the stranger became the needy one. In that sense, Williams’s cruising held the promise of another kind of emotional relief—each time it succeeded, he had been chosen, he had been taken in, he knew he was real. Having rejected his mother’s Puritan strictures, his Christian faith, his “normal” self, he embraced homosexuality’s “rebellious hell,” and with it, he claimed his animality. “I know myself to be a dog, but—animal nature no longer appears embarrassing in one’s self,” he wrote. “It has become so universally apparent in others.” “I wonder, sometimes, how much of the cruising was for the pleasure of my cruising partner’s companionship and for the sport of pursuit and how much was actually for the pretty repetitive and superficial satisfactions of the act itself,” Williams wrote of this period. “I know that I had yet to experience in the ‘gay world’ the emotion of love, which transfigures the act to something beyond it.”

You

coming toward me—

please

make

haste!

. . . (You—you—is

this

you?—‘Coming toward me?’)”) By being desired, Williams was emptied of need; the stranger became the needy one. In that sense, Williams’s cruising held the promise of another kind of emotional relief—each time it succeeded, he had been chosen, he had been taken in, he knew he was real. Having rejected his mother’s Puritan strictures, his Christian faith, his “normal” self, he embraced homosexuality’s “rebellious hell,” and with it, he claimed his animality. “I know myself to be a dog, but—animal nature no longer appears embarrassing in one’s self,” he wrote. “It has become so universally apparent in others.” “I wonder, sometimes, how much of the cruising was for the pleasure of my cruising partner’s companionship and for the sport of pursuit and how much was actually for the pretty repetitive and superficial satisfactions of the act itself,” Williams wrote of this period. “I know that I had yet to experience in the ‘gay world’ the emotion of love, which transfigures the act to something beyond it.”

IN JUNE 1940, “at the nadir of my resources, physical, mental, spiritual,” Williams took himself off to the artsy enclave of Provincetown, Massachusetts—“P-Town,” as it was called, an abbreviation that to Williams stood for “pilgrimage” in “mad pilgrimage of the flesh.” To his friends, he reported that life there was “beautiful and serene”; the result of a regimen that included “taking free conga lessons, working on a long, narrative poem, swimming every day, drinking every day, and fucking every night.” On one of those days, in a two-story shack on Captain Jack’s Wharf, which sat on stilts above the ebb and flow of the tide, Williams caught a glimpse of Kip Kiernan, to whom he would dedicate his first book of stories and whose pictures he would carry in his wallet until it was lost in the sixties. Kiernan, born Bernard Dubowsky, was a Canadian draft dodger who had invented a new name for himself and a new life in art. He and his roommate, Joe Hazan, who would become a confidant of Williams, had ambitions to be dancers; both took beginners’ classes at the Duval School of Ballet and then switched on partial scholarships to the American School of Ballet in Provincetown. “Neither of us had any talent at all in ballet,” Hazan said, adding of Kip, “He just didn’t have it. He wasn’t meant to be a dancer. He’d studied sculpture some place before.”

To Williams, Kip

was

sculpture. His well-proportioned muscular torso may have made him top-heavy as a dancer, but it made him perfect as an erotic ideal. “My good eye was hooked like a fish,” Williams wrote. (He had a cataract in one eye at the time.) “I will never forget the first look I had at him, standing with his back to me at the two-burner stove, the wide and powerful shoulders and the callipygian ass such as I’d never seen before! He didn’t talk much. I think he felt my vibes and was intimidated by my intensity.” Among the accessories to this splendid body were, according to Williams, “slightly slanted lettuce-green eyes, high cheekbones, and a lovely mouth.” “When he turned from the stove, I might have thought, had I been but a little bit crazier, that I was looking at the young Nijinsky,” Williams wrote; the Nijinsky parallel was one that Kip himself drew later “with Narcissan pride.” A few days later, Williams moved into Kiernan and Hazan’s clapboard bungalow on Captain Jack’s Wharf, sleeping on cots downstairs with Hazan while Kip slept upstairs in the single bedroom. “He had Southern charms, and Kip had a lot of charm,” Hazan remembered. “So it was easy to be friends with him. . . . The experience I had with Kip was that that he had been successful sexually with girls. I never had any indication of homosexuality, not the slightest in any way.”

was

sculpture. His well-proportioned muscular torso may have made him top-heavy as a dancer, but it made him perfect as an erotic ideal. “My good eye was hooked like a fish,” Williams wrote. (He had a cataract in one eye at the time.) “I will never forget the first look I had at him, standing with his back to me at the two-burner stove, the wide and powerful shoulders and the callipygian ass such as I’d never seen before! He didn’t talk much. I think he felt my vibes and was intimidated by my intensity.” Among the accessories to this splendid body were, according to Williams, “slightly slanted lettuce-green eyes, high cheekbones, and a lovely mouth.” “When he turned from the stove, I might have thought, had I been but a little bit crazier, that I was looking at the young Nijinsky,” Williams wrote; the Nijinsky parallel was one that Kip himself drew later “with Narcissan pride.” A few days later, Williams moved into Kiernan and Hazan’s clapboard bungalow on Captain Jack’s Wharf, sleeping on cots downstairs with Hazan while Kip slept upstairs in the single bedroom. “He had Southern charms, and Kip had a lot of charm,” Hazan remembered. “So it was easy to be friends with him. . . . The experience I had with Kip was that that he had been successful sexually with girls. I never had any indication of homosexuality, not the slightest in any way.”

One July night soon afterward, Williams declared his passion. His “crazed eloquence” silenced Kip for a few moments. Finally, Kip said, “Tom, let’s go up to my bedroom.” In a letter to Windham, Williams set down a unique account of his ravished surrender.

We wake up two or three times in the night and start all over again like a pair of goats. The ceiling is very high like the loft of a barn and the tide is lapping under the wharf. The sky amazingly brilliant with stars. The wind blows the door wide open, the gulls are crying. Oh, Christ. I call him baby . . . though when I lie on top of him I feel like I was polishing the Statue of Liberty or something. He is so enormous. A great bronze statue of antique Greece come to life. But with a little boy’s face. A funny up-turned nose, slanting eyes, and underlip that sticks out and hair that comes to a point in the middle of his forehead. I lean over him in the night and memorize the geography of his body with my hands—he arches his throat and makes a soft, purring sound. His skin is steaming hot like the hide of a horse that’s been galloping. It has a warm, rich odor. The odor of life. He lies very still for a while, then his breath comes fast and his body begins to lunge. Great rhythmic plunging motion with panting breath and his hands working over my body. Then sudden release—and he moans like a little baby. I rest with my head on his stomach. Sometimes fall asleep that way. We doze for a while. And then I whisper “Turn over.” He does. We use brilliantine. The first time I come in three seconds, as soon as I get inside. The next time is better, slower, the bed seems to be enormous. Pacific, Atlantic, the North American continent . . . And now we’re so tired we can’t move. After a long while he whispers, “I like you, Tenny.”—hoarse—embarrassed—ashamed of such intimate speech! And I laugh for I know that he loves me!—That nobody ever loved me before so completely. I feel the truth in his body. I call him baby—and tell him to go to sleep. After a while he does, his breathing is deep and even, and his great deep chest is like a continent moving slowly, warmly beneath me. The world grows dim, the world grows warm and tremendous. Then everything’s gone and when I wake up it is daylight, the bed is empty.—Kip is gone out.—He is dancing.—Or posing naked for artists. Nobody knows our secret but him and me. And now

you

, Donnie—because you can understand. Please keep this letter and be very careful with it. It’s only for people like us who have gone beyond shame!

In Williams’s description, Kip’s large size is associated with the female (the Statue of Liberty); Williams’s smallness places him in the position of an infant with his gargantuan mother. It’s a connection that Williams makes instinctively—moving directly from the account of Kip’s huge sculpted body to the image of his “little boy’s face.” For Williams, the experience was a movement of both men between the roles of mother and child, culminating in Kip’s surrender to Williams and Williams’s pleasure. “Last night you made me know what is meant by beautiful pain,” Kip told Williams the day after their first night together, as they walked on the dunes. “I know Kip loved me,” Williams wrote. Williams’s restless heart had found its object of desire. “I also know it couldn’t have been very easy to be waked up four or five times a night for repeated service of my desire. One morning he said: ‘Tenn, I’m too little and you’re too big.’ Well I was not ‘too big’—just sort of parlor-size as they put it in those days—but Kip did have an exceptionally small anal entrance and to be entered that way each night, well, it’s a wonder he didn’t come down with a fistula.”

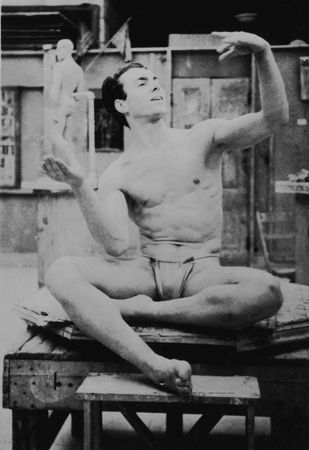

The dancer Kip Kiernan, his first love

In the midst of this emotional whirlwind, Williams’s old habit of blushing returned, tormenting his days, which he spent translating his riotous emotions—“ecstasy one moment—O dapple faun!—and consummate despair the next”—into the verse drama

The Purification

. After a while, according to his autobiography

Memoirs

, “Kip turned oddly moody. . . . We would go places together and he would suddenly not be there, and when he came to bed, after an absence of some hours, he’d explain gently, ‘I had a headache, Tenn.’ ” After a chamber music concert one night, Kip rushed off by himself. “Moves me to find someone afflicted as I am with mental conflicts,” Williams wrote in his diary. “Still it troubles me—this is so much what I need, what I want, what I have been looking for the past few months so feverishly. Seems miraculous. It is too good to be true.” He continued, “I fear his being lost to me already . . . oh, what an ache of emptiness I would have to endure—for now, for the first time in my life, I feel I am near to the great

real

thing that can make my life complete. Oh, K.—don’t stay away very long.—I’m lonely tonight.” Despite his fears about Kip—“Will it be all gone, will it still be there,” he wrote of Kip’s love on his way back to Provincetown from a quick trip to New York—Williams put on a braggadocio face. “I am being courted by a musician and a dancing instructor and a language professor, one of them has a big new Buick and drives us all over the Cape,” he wrote at the end of July. “They all want Kip but hope to English off me or something since he is apparently less accessible than me—an unmistakable bitch—I think love has made me young again, or maybe it’s the blue dungarees.”

The Purification

. After a while, according to his autobiography

Memoirs

, “Kip turned oddly moody. . . . We would go places together and he would suddenly not be there, and when he came to bed, after an absence of some hours, he’d explain gently, ‘I had a headache, Tenn.’ ” After a chamber music concert one night, Kip rushed off by himself. “Moves me to find someone afflicted as I am with mental conflicts,” Williams wrote in his diary. “Still it troubles me—this is so much what I need, what I want, what I have been looking for the past few months so feverishly. Seems miraculous. It is too good to be true.” He continued, “I fear his being lost to me already . . . oh, what an ache of emptiness I would have to endure—for now, for the first time in my life, I feel I am near to the great

real

thing that can make my life complete. Oh, K.—don’t stay away very long.—I’m lonely tonight.” Despite his fears about Kip—“Will it be all gone, will it still be there,” he wrote of Kip’s love on his way back to Provincetown from a quick trip to New York—Williams put on a braggadocio face. “I am being courted by a musician and a dancing instructor and a language professor, one of them has a big new Buick and drives us all over the Cape,” he wrote at the end of July. “They all want Kip but hope to English off me or something since he is apparently less accessible than me—an unmistakable bitch—I think love has made me young again, or maybe it’s the blue dungarees.”

In mid-August, according to Williams, “a girl”—Shirley Brimberg, who as Shirley Clarke later became a famous documentary filmmaker—“entered the scene.” Williams was on the dunes with a group of artists that included another still-unknown cultural star, Jackson Pollock, when a solemn-looking Kiernan appeared with his bike. “Tenn, I have to talk to you,” he said. With Kip perched on the handlebars, Williams rode into Provincetown. “On the way in, with great care and gentleness, he told me that the girl who had intruded upon the scene had warned him that I was in the process of turning him homosexual and that he had seen enough of that world to know that he had to resist it, that it violated his being in a way that was unacceptable to him.” One morning soon afterward, upstairs in Kip’s room, Williams “made a horrible ass of myself—insulting a stupid little girl” (he hurled a riding boot at Brimberg, “missing her, but not intentionally”) “because she had been instrumental in my unhappiness. Felt quite unnerved, almost hysterical—silly! The whole mess has got to end

now

—”

now

—”

It did. “

C’est fini

,” Williams wrote in his diary on August 15. He was overcome by a despair that echoed down the decades to the annihilating impotence of his solitary childhood. “I can’t save myself. Somebody has got to save me,” he wrote. “I shall have to go through the world giving myself to people until somebody will take me.” The loss, he wrote, “threatens to wreck me completely.” Deracinated and embattled, he prayed to God: “You whoever you are—who takes care of those beyond caring for themselves—please make some little charitable provision for the next few days of Tennessee.” Back in Manhattan, he frequently spoke Kip’s name to his diary: “Oh, K.—if only—only—

only

.” “K.—dear K.—I love you with all my heart. Goodnight.” He saved his parting shot for his only written letter to Kip: “I hereby formally bequeath you to the female vagina, which vortex will inevitably receive you with or without my permission.”

C’est fini

,” Williams wrote in his diary on August 15. He was overcome by a despair that echoed down the decades to the annihilating impotence of his solitary childhood. “I can’t save myself. Somebody has got to save me,” he wrote. “I shall have to go through the world giving myself to people until somebody will take me.” The loss, he wrote, “threatens to wreck me completely.” Deracinated and embattled, he prayed to God: “You whoever you are—who takes care of those beyond caring for themselves—please make some little charitable provision for the next few days of Tennessee.” Back in Manhattan, he frequently spoke Kip’s name to his diary: “Oh, K.—if only—only—

only

.” “K.—dear K.—I love you with all my heart. Goodnight.” He saved his parting shot for his only written letter to Kip: “I hereby formally bequeath you to the female vagina, which vortex will inevitably receive you with or without my permission.”

“Do you think I am making too much of Kip?” Williams asked the reader in a rhetorical line that was cut from

Memoirs

. “Well, you never saw him.” In a sense, Williams never stopped seeing Kip. At the time of their breakup, he wrote, “K., if you ever come back, I’ll never let you go. I’ll bind you to me with every chain that ingenuity of mortal love can devise!” Kip never came back (he married, then died of a brain tumor, in 1944, at the age of twenty-six); but through the alchemy of Williams’s stagecraft, in a sense, he also never went away.

Memoirs

. “Well, you never saw him.” In a sense, Williams never stopped seeing Kip. At the time of their breakup, he wrote, “K., if you ever come back, I’ll never let you go. I’ll bind you to me with every chain that ingenuity of mortal love can devise!” Kip never came back (he married, then died of a brain tumor, in 1944, at the age of twenty-six); but through the alchemy of Williams’s stagecraft, in a sense, he also never went away.

“Tennessee could not possess his own life until he had written about it,” Gore Vidal observed. “To start with, there would be, let us say, a sexual desire for someone. Consummated or not, the desire . . . would produce reveries. In turn, the reveries would be written down as a story. But should the desire still remain unfulfilled, he would make a play of the story and then—and this is why he was so compulsive a working playwright—he would have the play produced so he could, at relative leisure, like God, rearrange his original experience into something that was no longer God’s and unpossessable but

his

.” Vidal continued: “The sandy encounters with his first real love, a dancer on the beach at Provincetown, and the dancer’s later death (‘an awful flower grew in his brain’), instead of being forever lost, were forever his once they had been translated to the stage.”

his

.” Vidal continued: “The sandy encounters with his first real love, a dancer on the beach at Provincetown, and the dancer’s later death (‘an awful flower grew in his brain’), instead of being forever lost, were forever his once they had been translated to the stage.”

Other books

Free Fall by Jill Shalvis

Menace in Christmas River (Christmas River 8) by Meg Muldoon

Imajica (Vol. 1): El Quinto Dominio by Clive Barker

100 Million Years of Food by Stephen Le

Seduced by Stratton (The English Brothers Book 4) by Katy Regnery

The Ragtime Fool by Larry Karp

Infinity in the Palm of Her Hand: A Novel of Adam and Eve by Belli, Gioconda

Mommy! Mommy! by Taro Gomi

Temple of the Dragonslayer by Waggoner, Tim

The Morcai Battalion by Diana Palmer