Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (85 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

7.01Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

For all its narrative problems,

Clothes for a Summer Hotel

is a much better written and more evocative play than the version those first-nighters saw. As Williams wrote to Kazan, “ ‘Clothes’ was a victim of a bad first act, miscasting of Scott”—who was played by the British actor Kenneth Haigh—“a stingy producer, and Gerry Page’s problem with projecting her voice, so bad that all the theatres we played had to be miked. Much as I love Quintero, he vacillated too much over crucial problems, in my opinion.” Nonetheless, in a desperate gesture, so that word of mouth would have time to build, Williams stumped up twenty thousand dollars to help cover the costs for a second week. “Couldn’t the son of a bitch at least let us get out quick?” Page said on hearing the news. The actors got out quick enough. The play closed on Easter Sunday, having played seven previews and fifteen performances in New York, twenty-three shows in Chicago, and thirty-nine shows in Washington, and losing the best part of half a million dollars. Williams told Earl Wilson, the

New York

Post

’s gossip columnist, that he’d been a victim of “critical homicide.” He vowed never to return to Broadway, which was just as well because his illustrious career on the Rialto was over.

Clothes for a Summer Hotel

is a much better written and more evocative play than the version those first-nighters saw. As Williams wrote to Kazan, “ ‘Clothes’ was a victim of a bad first act, miscasting of Scott”—who was played by the British actor Kenneth Haigh—“a stingy producer, and Gerry Page’s problem with projecting her voice, so bad that all the theatres we played had to be miked. Much as I love Quintero, he vacillated too much over crucial problems, in my opinion.” Nonetheless, in a desperate gesture, so that word of mouth would have time to build, Williams stumped up twenty thousand dollars to help cover the costs for a second week. “Couldn’t the son of a bitch at least let us get out quick?” Page said on hearing the news. The actors got out quick enough. The play closed on Easter Sunday, having played seven previews and fifteen performances in New York, twenty-three shows in Chicago, and thirty-nine shows in Washington, and losing the best part of half a million dollars. Williams told Earl Wilson, the

New York

Post

’s gossip columnist, that he’d been a victim of “critical homicide.” He vowed never to return to Broadway, which was just as well because his illustrious career on the Rialto was over.

In 1976, at his induction to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Williams had heard the words of Robert Penn Warren: “No dramatist writing in English has created a more strongly characteristic and memorable world.” At the Kennedy Center Honors, in 1979, he heard Kazan call him “a playwright in the way that a lion is a lion. Nothing but.” Accepting the 1980 Presidential Medal of Freedom, Williams heard President Jimmy Carter say that he’d “shaped the history of modern American theater.” But for the remainder of his life, Williams never heard a major American critic praise a new play of his.

“I WILL NEVER recover from what they did to me with ‘Clothes,’ ” Williams wrote to Mitch Douglas, his new representative at ICM. (Barnes had left the agency.) “But I will not stop working till they drop me in the sea. . . . I think I know better than anyone how little time there’s left for me. I’ll use it well. I trust you to help me with it.” Douglas had been a Williams fan before he became a Williams functionary; he had read every published work. He was firm, feisty, and fun. He began at ICM as a temp typist between acting jobs; in 1974, he became a full-time agent, and by 1978 Williams was his client. “Tennessee was difficult because Tennessee was crazy. There’s no diplomatic way to say that,” Douglas said. “He ate Bill Barnes alive. One of the reasons Billy was out at ICM was because Tennessee was taking all his time. I was told, ‘Don’t let him take up all your time the way it was with Billy Barnes.’ ” Williams’s literary life—the calls, the productions, the correspondence, the personal appearances, the travel—was a three-ring circus, of which Douglas became the harassed ringmaster.

On his first trip to Key West, to discuss

Stopped Rocking

, Douglas called Williams from his hotel and asked to come over. “Well, that would be difficult,” Williams said. “Robert got wasted last night and wrecked the car. Now he’s sitting on the front porch with a gun in his lap threatening to blow the brains out of anyone who approaches. I would say we’re under siege.” Douglas quickly learned that to handle his new client, strict boundaries would have to be maintained. When St. Just called him to complain about Williams’s New York apartment—“Mitch, the windows are filthy and the floors are even worse”—Douglas told her, “I don’t do windows. You want a maid, call a maid service. You need some help with business, I’ll be happy to help.” Inevitably, though, even the no-nonsense Douglas sometimes had to deal with Williams’s transgressive antics. At the Kennedy Center Honors luncheon, for instance, Williams and Maureen Stapleton got drunk. After lunch, as they waited for their limousine, a Marine band was playing beside the driveway. Stapleton went up to the conductor. “You guys play so fucking good. Do you know ‘Moon River’?” she said. The band struck up the song. Stapleton and Williams began dancing; they waltzed themselves into a forbidden area of the White House. “I went to the Sergeant of Arms, and I said, ‘Will you help me get them out of here?’ ” Douglas recalled. “Two Marines got under Tennessee and two under Maureen’s arm. They walked them to the limo.”

Stopped Rocking

, Douglas called Williams from his hotel and asked to come over. “Well, that would be difficult,” Williams said. “Robert got wasted last night and wrecked the car. Now he’s sitting on the front porch with a gun in his lap threatening to blow the brains out of anyone who approaches. I would say we’re under siege.” Douglas quickly learned that to handle his new client, strict boundaries would have to be maintained. When St. Just called him to complain about Williams’s New York apartment—“Mitch, the windows are filthy and the floors are even worse”—Douglas told her, “I don’t do windows. You want a maid, call a maid service. You need some help with business, I’ll be happy to help.” Inevitably, though, even the no-nonsense Douglas sometimes had to deal with Williams’s transgressive antics. At the Kennedy Center Honors luncheon, for instance, Williams and Maureen Stapleton got drunk. After lunch, as they waited for their limousine, a Marine band was playing beside the driveway. Stapleton went up to the conductor. “You guys play so fucking good. Do you know ‘Moon River’?” she said. The band struck up the song. Stapleton and Williams began dancing; they waltzed themselves into a forbidden area of the White House. “I went to the Sergeant of Arms, and I said, ‘Will you help me get them out of here?’ ” Douglas recalled. “Two Marines got under Tennessee and two under Maureen’s arm. They walked them to the limo.”

Feeling that “time runs short,” and determined to live in the slipstream of his fame, Williams proved increasingly difficult for Douglas to wrangle. In July 1981, a few months before the Off-Broadway premiere of

Something Cloudy, Something Clear

—a memory play in which the adult Williams revisited and commented on his first experience of love, with Kip Kiernan, in 1940—Williams wrote to Douglas suggesting that they “level with each other.” “Let’s do,” Douglas replied; in a piquant, four-page, single-spaced letter he made clear a lot of what was cloudy in Williams’s behavior:

Something Cloudy, Something Clear

—a memory play in which the adult Williams revisited and commented on his first experience of love, with Kip Kiernan, in 1940—Williams wrote to Douglas suggesting that they “level with each other.” “Let’s do,” Douglas replied; in a piquant, four-page, single-spaced letter he made clear a lot of what was cloudy in Williams’s behavior:

You’ve been quoted in the press saying that you did not approve the STREETCAR remake deal and the negotiations went forward without your knowledge. Also you’ve stated that you never approved of Sylvester Stallone as Stanley. Obviously you’ve forgotten that we discussed the possibility of selling these rights for a year before the Martin Poll negotiation began. When I told you I could get a lot of money—$750,000 or a million—for these rights, but Stallone would be included as Stanley, you indicated that you didn’t care if Stanley were played by a banana. You indicated that you needed the money and might as well have it while you were around—“I’m not interested in anything posthumous.” And I do agree with you. You’ve worked long, hard and well and should enjoy the rewards—and

now

. When the Jerry Parker

Newsday

article appeared quoting you as saying you didn’t know about the deal and that Stallone was a “terrible actor,” you called me denying the story, asking to get a denial and attributing the comment to one of the several people in the room with you when Parker was interviewing you. I got a denial through Liz Smith, and within a day you went to North Carolina and made the same comments to a different set of reporters. Stallone has walked out of the project. Martin Poll wants to honor the deal and put it together with a cast of your approval in spite of the fact that none of the major studios think that STREETCAR is now a hot property, and in fact the highest previous offer I could get was $250,000. Do you want this $750,000 deal . . . or not? A simple yes or no will do.

You also commented in North Carolina, “Not only do I work very hard but I have to represent myself as well. My representative is only interested in using me for profit.” I resent this type of abusive statement. I work very hard for you and always with a two-fold purpose: to do the best for you artistically and financially. When I book you at the Jean Cocteau Repertory Theatre [

Something Cloudy, Something Clear

] or allow you to sign for a small film such as THE STRANGEST KIND OF ROMANCE, it isn’t for the money—it’s for the artistic merit and for the possibilities of getting a work done that otherwise might not be done, with the hope of future financial rewards. I’m sorry, but your plays since IGUANA haven’t done well financially and you aren’t an easy sale commercially. I try to offset the not-for-profit situations, since you often cry, “I’m not a wealthy man,” with sales like that of STREETCAR to the movies. . . .

Yes, Tennessee, let’s level with each other. You wrote recently of Audrey Wood saying theatre people are often impossible people and that you were never an easy client for Audrey even from the beginning. Well let me confirm something I think you already know—You aren’t an easy client now. You’re inconsistent, unreliable, you make commitments you don’t honor and your attitude and approach are often less than gentlemanly. . . .

. . . You attack me in Chicago because ICM didn’t send you a birthday telegram. I reply, “But Tennessee, I

came

.” “Well, baby we all come sometime if we’re lucky!” Or in Orlando, “I want my wine in an opaque glass. Mitch, do you know how to spell opaque?” I have a duty to you, but it doesn’t include being abused by you. . . .

Also in your recent comments about Audrey you said that Audrey understood. I think I understand too, Tennessee. We come from the same area, have the same background (good lord, we even have the same birthday), and like you I’ve worked hard to attain my position as a skilled professional. . . . You

are

our greatest American playwright, living or dead, and it’s a honor for me to be associated with you. . . . But I must also tell you, dear Tennessee, that I don’t intend to have my first heart attack because of you.

Williams dismissed “Bitch Douglas” gently but immediately. “I wish you luck and I do believe that you wish me the same,” he wrote, adding, in a reference to the last ICM agent he’d fired, “I know that you’d never draw back your hand and make a hissing sound if I pass your table at the Algonquin.” To Milton Goldman, the head of the agency’s theater division, Williams wrote, “Can you place me in the hands of some agent at ICM who is not and never was one of ‘Miss Wood’s’ people!?” From then on, Goldman, who represented actors, fronted as Williams’s agent while Douglas did the work. “I will not again open an envelope with his name on it,” Williams wrote to Goldman, adding, “What most concerns me is that if Mitch does not do the graceful and dignified thing (for me and ICM) he will still have his hand in my affairs when I split the scene which I think is not long away.”

IN HIS REVIEW of

Clothes

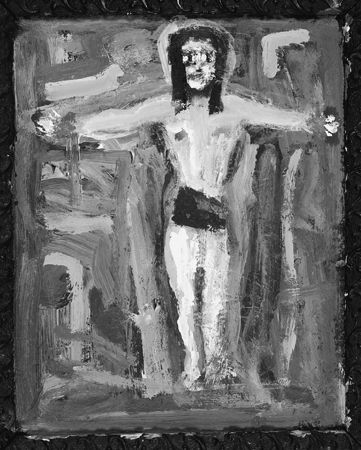

for a Summer Hotel, Harold Clurman argued that Williams’s creative practice had become disconnected from his inner self. On the contrary, the apparitions, the shadowy reality, the double exposures of past speaking to present and present to past that dominate Williams’s thin late plays dramatize precisely the retreat of his attenuated self—a self that had been desiccated by his adamantine will to write. The activity that had given him life also gave him death. “There are periods in life when I think that I want death, despite my long struggle against it all these years,” Williams wrote to Oliver Evans at the beginning of 1981. Edwina Williams died in June 1980. (Gore Vidal referred to her as “666” in his condolence note; “that stands for ‘The Beast of the Apocalypse,’ ” Williams explained to Kazan.) Audrey Wood, who had been a kind of surrogate mother for thirty-one years, had a stroke in 1981 and never regained consciousness. Williams sent one of his paintings—

Christ on a Cross

—to Wood’s nursing home, where it hung over her bed for the four years she clung to life. Williams saw “a long, long stretch of desolation about me, now at the end.” Even his handwriting signaled a shift; the bold flow of his signature was suddenly feathery, no longer an assertion of energy and confidence. “When I am very ill, as I am now—diseased pancreas and liver—I am unable to carry out even the most important things that I should do,” he told Evans at the beginning of 1981, adding, “It is only good to think back on the times when life was lovely—at least comparatively.”

Clothes

for a Summer Hotel, Harold Clurman argued that Williams’s creative practice had become disconnected from his inner self. On the contrary, the apparitions, the shadowy reality, the double exposures of past speaking to present and present to past that dominate Williams’s thin late plays dramatize precisely the retreat of his attenuated self—a self that had been desiccated by his adamantine will to write. The activity that had given him life also gave him death. “There are periods in life when I think that I want death, despite my long struggle against it all these years,” Williams wrote to Oliver Evans at the beginning of 1981. Edwina Williams died in June 1980. (Gore Vidal referred to her as “666” in his condolence note; “that stands for ‘The Beast of the Apocalypse,’ ” Williams explained to Kazan.) Audrey Wood, who had been a kind of surrogate mother for thirty-one years, had a stroke in 1981 and never regained consciousness. Williams sent one of his paintings—

Christ on a Cross

—to Wood’s nursing home, where it hung over her bed for the four years she clung to life. Williams saw “a long, long stretch of desolation about me, now at the end.” Even his handwriting signaled a shift; the bold flow of his signature was suddenly feathery, no longer an assertion of energy and confidence. “When I am very ill, as I am now—diseased pancreas and liver—I am unable to carry out even the most important things that I should do,” he told Evans at the beginning of 1981, adding, “It is only good to think back on the times when life was lovely—at least comparatively.”

Williams’s painting of the Crucifixion

Williams’s memory plays were written in this wistful vein; blending elegance and anxiety, they failed to make his turbulent hauntedness dynamic. “There’s an explosive center to ‘Something Cloudy, Something Clear’—if only Mr. Williams would light the fuse,” Frank Rich wrote in the

New York

Times

. In his final full-length play,

A House Not Meant to Stand: A Gothic Comedy

, a “spook sonata” that was almost giddy with bleakness, however, Williams lit the fuse and turned his sense of being a “still living remnant” into something savage and sensational.

New York

Times

. In his final full-length play,

A House Not Meant to Stand: A Gothic Comedy

, a “spook sonata” that was almost giddy with bleakness, however, Williams lit the fuse and turned his sense of being a “still living remnant” into something savage and sensational.

“Never, never, never stop laughing!” Williams counseled Truman Capote, during his “period of disequilibrium.” Williams practiced what he preached. Developed in three versions at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago between 1980 and 1982—it began as the one-act

Some Problems for the Moose Lodge

—

A House Not Meant to Stand

was a complete stylistic departure. In its embrace of the comic grotesque, it announced Williams’s refusal to suffer. The play’s aspiration—to combine stage mayhem with moral outrage—also broadcast the influence of the British playwright Joe Orton, to whom Williams dedicated

The Everlasting Ticket

, a play he worked on during the eighteen-month gestation of

A House Not Meant to Stand

. “I don’t compete with Joe Orton. I love him too much,” Williams said at the time. Nonetheless, he adapted Orton’s game of dereliction, delirium, and denial into his own allegory of decay.

Some Problems for the Moose Lodge

—

A House Not Meant to Stand

was a complete stylistic departure. In its embrace of the comic grotesque, it announced Williams’s refusal to suffer. The play’s aspiration—to combine stage mayhem with moral outrage—also broadcast the influence of the British playwright Joe Orton, to whom Williams dedicated

The Everlasting Ticket

, a play he worked on during the eighteen-month gestation of

A House Not Meant to Stand

. “I don’t compete with Joe Orton. I love him too much,” Williams said at the time. Nonetheless, he adapted Orton’s game of dereliction, delirium, and denial into his own allegory of decay.

At curtain rise, the decrepit Cornelius and Bella McCorkle are returning, at midnight, to their dilapidated, rain-swept Mississippi house, which has a perpetually leaky roof and a threadbare interior, whose “panicky disarray” is intended “to produce a shock of disbelief.” The first sound of the play is “a large mantel clock,” which “ticks rather loudly for about half a minute before there is the sound of persons about to enter the house.” The relentlessness of time is the issue. The imminent threat of structural collapse is meant as “a metaphor for the state of society,” Williams says in the play’s first stage direction. (The epigram, by Yeats, is equally explicit: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”) In its loquacious Southern way, the play aspires to a kind of farce momentum: at a certain speed all things disintegrate. But as Williams’s alternative titles for the play indicate—“A House Not Meant to Last Longer Than the Owner,” “The Disposition of the Remains,” “Terrible Details,” “Putting Them Away”—he was also prefiguring his own ending. The play talks about the specter of “sinister times”—nuclear war, inflation, overpopulation—but the haunting it demonstrates is Williams’s.

Other books

Fiends of the Rising Sun by David Bishop

Finding Promise by Scarlett Dunn

An Accidental Shroud by Marjorie Eccles

Nurjahan's Daughter by Podder, Tanushree

Indestructible by Angela Graham

Cheaper to Keep Her (part 1) by Swinson presents Unique, Kiki

6.0 - Raptor by Lindsay Buroker

The Mystery at the Calgary Stampede by Gertrude Chandler Warner

Beauty and the Wolf / Their Miracle Twins by Faye Dyer, Lois, Logan, Nikki

Silent Whisper by Andrea Smith