Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (43 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

11.61Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And on that morning—

precociously—for always—

you lost belief

in everything but loss,

gave credence only to doubt,

and began even then,

as though it were always intended,

to form in your heart

the cortege of future betrayals—

the loveless acts

of crude and familiar knowledge.

Even as he awaited the operation, which was called off at the last minute because the doctors thought better of it, Williams castigated himself for his fears (“I’m such a coward, oh, such a damned sniveling coward. It does disgust me so.”); for his panicky hypersensitivity (“Anything strange upsets me”); and for his debasing loneliness (“Waiting for Frank like a dog for his bone and his master!”). Apocalyptic foreboding filled his diary: “If I am ever even relatively well again and free from pain I hope I will remember how this was.” Williams clung to the memory of his few loved ones, listing them almost like talismans against his fear of cancer, a diagnosis that he “whispered” to himself. “Suppose someone said to me, Tennessee, you have cancer? How would I take it? Probably not well. And yet I suspect that I do.” Nonetheless, when Oliver Evans visited him in the hospital on New Year’s Day, and reported a conversation with Williams’s doctor about the benign hemorrhoids, Williams took umbrage at even the mention of cancer. “He says you should have an operation as it could become malignant,” Evans said. “I thought the remark at least unnecessary,” Williams wrote in his diary, adding, “He has impulses of shocking cruelty sometimes.”

More to the point was Williams’s cruelty to himself. His New Year’s resolution was to give up “that old breast-beating.” About to leave the hospital, he resolved “to make no more incontinent demands on the exhausted artist. Let him rest. Even let him expire if his term is over. But since I want life, even without Creation, I must not whip myself for not doing what I’ve stopped being able to do. Whether the failure be only a while, or longer, or always.”

“Oh, how I long to be loose again, entering the Key West studio for morning work, with the sky and the Australian pines through the sky light and clear morning light on all four sides and the warmth of coffee in me and the other world of creation,” Williams wrote from the hospital on New Year’s Day, 1954. By the third week of January, he

was

back in the sweet solitude of Key West with his grandfather, filled with a sense of both relief and release. “I am doing what I dreamed of doing again,” he wrote. “Clear mornings, coffee, the studio—quiet, serene. But the Muse is not attracted. Not today.”

was

back in the sweet solitude of Key West with his grandfather, filled with a sense of both relief and release. “I am doing what I dreamed of doing again,” he wrote. “Clear mornings, coffee, the studio—quiet, serene. But the Muse is not attracted. Not today.”

A similarly potent constellation of warring internal forces—death and creativity, fear and freedom, doom and gladness—had occurred only once before in Williams’s life. In 1947, after the trauma of his Taos hospital experience, Williams had sat down and projected, he said, “all the emotional content of the long crisis” into

A Streetcar Named Desire

. “Despite the fact that I thought I was dying, or maybe because of it, I had a great passion for work,” he wrote in his

Memoirs

.

A Streetcar Named Desire

. “Despite the fact that I thought I was dying, or maybe because of it, I had a great passion for work,” he wrote in his

Memoirs

.

Now, seven years later, in the spring of 1954, Williams picked up “A Place of Stone,” a short play that he hadn’t been able to “get a grip on” when he started it the previous year and that had added to his “terrible state of depression last summer in Europe.” In March, he wrote to Wood about it. “I’m . . . pulling together a short-long play based on the characters in ‘Three Players’,” he said. “Don’t expect that till you see it, as I might not like it when I read it aloud.” Nonetheless, within a week, although he judged the new play too brief and too wordy, Williams clearly saw that he had found a new imaginative seam. “I do think it has a terrible sort of truthfulness about it, and the tightest structure of anything I have done. And a terrifyingly strong final curtain.” Back in Rome that summer, when Wood was visiting, Williams handed her a pile of pages he called his “work script,” typed mostly on hotel stationery. By then the play was called

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

. Wood stayed up reading until four in the morning. “I was terribly excited,” she said. “In the morning I immediately told him this was certainly his best play since ‘Streetcar’, and it would be a great success. He may not remember this now, but he was then overwhelmed by my enthusiasm. It was obvious to me that he didn’t yet know what he had done.”

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

. Wood stayed up reading until four in the morning. “I was terribly excited,” she said. “In the morning I immediately told him this was certainly his best play since ‘Streetcar’, and it would be a great success. He may not remember this now, but he was then overwhelmed by my enthusiasm. It was obvious to me that he didn’t yet know what he had done.”

When Williams showed Wood the working script, he was, he said, “passing through, and still not out of, the worst nervous crisis of my nervous existence.” During that parlous summer of 1954, he had arrived “at just about the pit.” “I’m just holding on,” he wrote in his notebook in June. “Liquor and Seconal are my only refuge and they not unfailing.” Williams’s diaries also report a rueful hardening of his heart about love. “Am I worthy of it? Is anybody ever? We’re all such pigs, I am one of the biggest”; “my soul, if I have one still, sighs. And shudders and sickens.” In 1940, he had confessed to Margaret Webster, the director of

Battle of Angels

, that he had “begun to develop a sort of insulation about my feelings so I won’t suffer too much.” She replied, “That’s a very dangerous thing for a writer.” The observation had caught Williams’s attention; he recounted it to Kenneth Tynan, fifteen years later. “Once the heart is thoroughly insulated, it’s also dead,” he said. “My problem is to live with it, and to keep it alive.” At an emotional nadir, in his helplessness, he prayed for the intercession of a commanding presence, whose strength would resuscitate him. “Maybe Frank can help me. Maybe Maria will help me. Maybe God will help me,” he wrote in his diary. In the end, Williams helped himself.

Battle of Angels

, that he had “begun to develop a sort of insulation about my feelings so I won’t suffer too much.” She replied, “That’s a very dangerous thing for a writer.” The observation had caught Williams’s attention; he recounted it to Kenneth Tynan, fifteen years later. “Once the heart is thoroughly insulated, it’s also dead,” he said. “My problem is to live with it, and to keep it alive.” At an emotional nadir, in his helplessness, he prayed for the intercession of a commanding presence, whose strength would resuscitate him. “Maybe Frank can help me. Maybe Maria will help me. Maybe God will help me,” he wrote in his diary. In the end, Williams helped himself.

His feverish internal debate—between the dead heart and the outcrying heart—was built into the early structure of the script, which laid out the battle between the despondent, alcoholic Brick, son of Big Daddy Pollitt, “the Delta’s biggest cotton-planter,” and his beautiful, frustrated wife, Maggie, who wants both her husband’s love and an heir to claim her dying father-in-law’s wealth. “In this version, if you had a scene between Brick and Maggie, the first scene would be written from Brick’s point of view,” Wood recalled. “Then you’d turn a page and there would be the same scene from Maggie’s point of view. Page after page it went on.” Williams came to understand the play as “a synthesis of all my life.” In Brick and Maggie’s battle, Williams projected the war inside himself between self-destruction and creativity—his desire to reclaim his literary inheritance.

Brick, on crutches—he has broken an ankle in a drunken attempt to relive his glory days as a high-school athlete—is literally and metaphorically hobbled by his melancholy. He is, as his name indicates, inert. His life is the living death of resignation; he has thrown in the towel. Brick is not only blocked; he is a charming, laidback refusenik who stonewalls the world with drink, cutting himself off from fear, loathing, and life. “A man can be scared and calm at the same time,” Williams had noted in the New Orleans hospital. Brick personifies this infuriating passivity: he makes himself blank to his own desires. His deepest psychic relationship is with alcohol, which serves as a kind of mother, to nourish, calm, and contain him. “This click that I get in my head that makes me peaceful, I got to drink till I get it,” he explains to his father, Big Daddy. “It’s just a mechanical thing, something like a—like a—like a—switch clicking off in my head, turning the hot light off and the cool night on and—all of a sudden there’s—peace!”

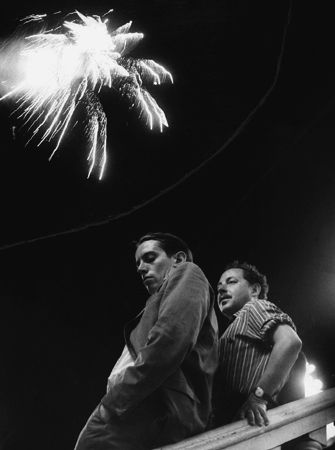

With British theater critic Kenneth Tynan at a festival in Valencia, Spain

Brick is a monument to absence. He enacts onstage the same tactics that Williams did in life: he is compelling enough for other people to want to help him, but he never actually changes. His behavior inspires concern, but he feels concern for no one. His indifference is perverse. He externalizes the inner world of the hysteric—what Masud Khan calls “a cemetery of refusals”—in which the most sensational is his refusal to bed his beautiful wife. Maggie’s goal throughout the play is to coax Brick back between the sheets, but, as far as he’s concerned, Maggie the Cat can jump off that roof and take up with someone else who will satisfy her sexually.

Maggie, by contrast, is all combat: her hat, as she says, is in the ring, and she’s determined to win. She wants Brick; she wants life; she wants, especially, to create a new life with Brick. “Born poor, raised poor, expect to die poor unless I manage to get us something out of what Big Daddy leaves when he dies of cancer,” she confesses to Brick, who blames her for the death of Skipper, his beloved friend and former football teammate. As Brick lashes out at Maggie, just missing her with swipes of his crutch, she forces him to face the truth: “

Skipper is dead! I’m alive!

Maggie the cat is—alive! I am alive, alive! I am alive!” She can still make a baby, she tells him; they can still claim their inheritance. “But how in hell on earth do you imagine—that you’re going to have a child by a man that can’t stand you?” Brick says. “That’s a problem I will have to work out,” Maggie replies.

Skipper is dead! I’m alive!

Maggie the cat is—alive! I am alive, alive! I am alive!” She can still make a baby, she tells him; they can still claim their inheritance. “But how in hell on earth do you imagine—that you’re going to have a child by a man that can’t stand you?” Brick says. “That’s a problem I will have to work out,” Maggie replies.

“Did Brick love Maggie?” Williams wrote in a subsequent defense of his characters. “He says with unmistakable conviction: ‘One man has one great good true thing in his life, one great good thing which is true. I had friendship with Skipper, not love with you, Maggie, but friendship with Skipper . . .’—But can we doubt that he was warmed and charmed by this delightful girl, with her vivacity, her humor, her very admirable pluckiness and tenacity, which are almost the essence of life itself? Of course, now that he has really resigned from life, retired from competition, removed his hat from the ring, now that he wants only things that are cool, such as his ‘click’ and cool moonlight on the gallery and the deadening of recollection that liquor gives, her tormented face, her anxious voice, strident with the heat of combat, is unpleasantly, sometimes even odiously, disturbing to him. But Brick’s overt sexual adjustment was, and must always remain, a heterosexual one. . . . He is her dependent.”

Through Maggie, Williams gave a voice to his own imminent emotional atrophy. “I’ve gone through this—

hideous!—transformation,

become—

hard! Frantic!—cruel!!

” she tells Brick in the first minutes of the play. For Williams to keep his heart open, he had to lacerate it. “I never could keep my finger off a sore,” Maggie says. Neither could Williams. Writing to Crawford in June 1954 (and, incidentally, asking her to recommend a stateside psychoanalyst for when he returned), Williams noted, “There is torment in this play, violence and horror—it is the under kingdom, all right!—that reflects what I was going through, or approaching, as I wrote it.” He added, “Perhaps if I had not been so tormented myself it would have been less authentic. Because I could not work with the old vitality, I had to find new ways and may have found some.”

hideous!—transformation,

become—

hard! Frantic!—cruel!!

” she tells Brick in the first minutes of the play. For Williams to keep his heart open, he had to lacerate it. “I never could keep my finger off a sore,” Maggie says. Neither could Williams. Writing to Crawford in June 1954 (and, incidentally, asking her to recommend a stateside psychoanalyst for when he returned), Williams noted, “There is torment in this play, violence and horror—it is the under kingdom, all right!—that reflects what I was going through, or approaching, as I wrote it.” He added, “Perhaps if I had not been so tormented myself it would have been less authentic. Because I could not work with the old vitality, I had to find new ways and may have found some.”

Rather like an actor who stays in character offstage in order not to lose the reality of his performance, Williams had begun to intuit the utility of his masochism, to become a connoisseur of his own collapse. In

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

, his friend Donald Windham correctly sussed a sea change in his writing; he called it a shift from self-dramatization to self-justification. “I’m not sure self-pity is the right term,” Williams wrote to

Time

critic Ted Kalem, who had come to the same conclusion as Windham. “In the case of the ‘highly personal’ writer, I wonder if ‘self-examination’ isn’t a more accurate way to put it. Does this make sense to you?” In fact, the shift in Williams was to self-cannibalization. He was prepared to destroy himself for meaning. He took himself right up to the precipice, so that he could stare into it.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

, his friend Donald Windham correctly sussed a sea change in his writing; he called it a shift from self-dramatization to self-justification. “I’m not sure self-pity is the right term,” Williams wrote to

Time

critic Ted Kalem, who had come to the same conclusion as Windham. “In the case of the ‘highly personal’ writer, I wonder if ‘self-examination’ isn’t a more accurate way to put it. Does this make sense to you?” In fact, the shift in Williams was to self-cannibalization. He was prepared to destroy himself for meaning. He took himself right up to the precipice, so that he could stare into it.

While Williams was creating a drama around Brick’s permanent state of inebriation, he, too, had formed an unrepentant appetite for what he jauntily called “a drinky-pie”:

When you’re feelin sorry

when you start to sigh,

honey, what you’re needin

is a

little

drinky-pie.

Yes, honey, what you’re cravin

is a little drinky-pie.

Two or three ain’t nothin,

three or four won’t make you high,

but the fifth drink is the number

that I call a drinky-pie!

. . . You’ll bust the sky wide open

with a little drinky-pie.

Drink a

little

drinky-pie, love,

drink a little drinky-pie

Such anthems aside, Williams’s drinking was no laughing matter. “It has gotten so bad,” he admitted to Crawford, “I don’t dare to turn down a street unless I can sight a bar not more than a block and a half down it.” He added, “Sometimes I have to stop and lean against a wall and ask somebody with me to run ahead and bring me a glass of cognac from the bar.” Williams was becoming simultaneously an actor and a voyeur, an exhibitionist and a spectator of his own suffering. He was scaring himself into new literary life.

“FOR THE NEW YEAR: may you write a play and may I direct it,” Elia Kazan had written Williams on Christmas Day, 1953. Seven months later, Williams granted Kazan his wish. In July, Wood sent him

Orpheus Descending

; by mid-August, Kazan declared his enthusiasm, dangling the possibility of a December production. “Of course I wrote it for you as I have all of my plays since ‘Streetcar’ but I had little hope that you would have the time or want to do it, probably as a result of Cheryl [Crawford]’s discouraging reaction,” Williams replied, while reminding Kazan that another director, Joe Mankiewicz, was also in the hunt. He went on:

Orpheus Descending

; by mid-August, Kazan declared his enthusiasm, dangling the possibility of a December production. “Of course I wrote it for you as I have all of my plays since ‘Streetcar’ but I had little hope that you would have the time or want to do it, probably as a result of Cheryl [Crawford]’s discouraging reaction,” Williams replied, while reminding Kazan that another director, Joe Mankiewicz, was also in the hunt. He went on:

Other books

2 Death of a Supermodel by Christine DeMaio-Rice

The Lottery and Other Stories by Jackson, Shirley

Taken by Storm: A Raised by Wolves Novel by Barnes, Jennifer Lynn

Orpheus and the Pearl & Nevermore by Kim Paffenroth

Blood and Feathers by Morgan, Lou

Mexico by James A. Michener

The Downing Street Years by Margaret Thatcher

Away in a Manger by Rhys Bowen

Rick's Reluctant Mate by Alice Cain

Along The Fortune Trail by Harvey Goodman