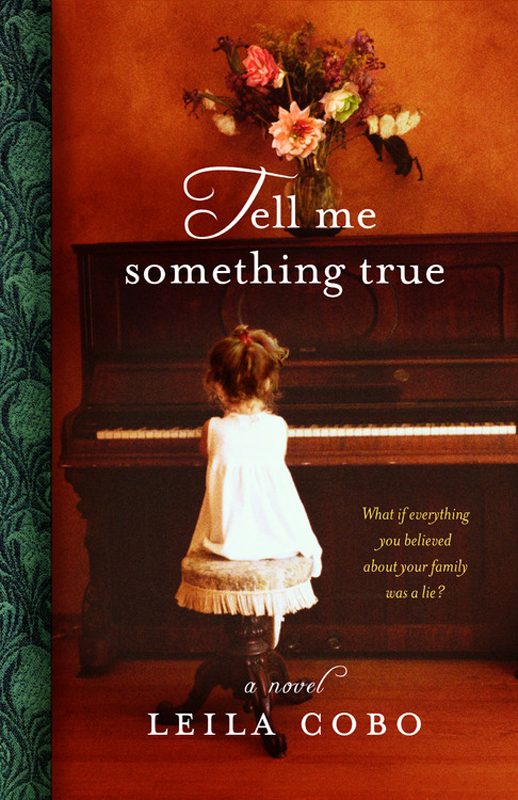

Tell Me Something True

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by Leila Cobo

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

www.twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First eBook Edition: October 2009

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-55827-3

Contents

To my mother, Olga, who inspired this story,

and to the Hanlon circle: Arthur, Allegra,

and Arthur III.

T

here is a picture of my mother. She’s kneeling in front of a bed of roses in the garden of our Los Angeles home, one hand

holding down a huge straw hat against an obvious gust of wind, the other clutching weeds and roots she’s just dug up from

the moist soil. Her long, curly hair is blowing around her face, and she’s smiling and she looks beautiful and impossibly

happy.

I had that picture in my bedroom, and it was my favorite for many years, before I learned that my mother hated gardening.

That every plant she ever touched died. That the beautiful day in that beautiful garden was a fluke. That at the time that

picture was taken, she was probably already thinking of another life, another place, far from me, far from us.

T

he air feels sweet and moist and just the slightest bit warm when you get off the 9 p.m. flight to Cali. It clings to your

skin, but in the faintest, most tenuous way, like the sheerest of gauze blouses touching but not touching your arms as you

breathe. When Gabriella tries to explain the sensation to her friends, they just don’t get it.

“How can you feel or smell any air,” they always ask, “if you arrive into an airport terminal?’

“It’s not a real terminal,” she is forever responding. And it isn’t, to her at least. It’s a building with open windows and

no air-conditioning, and if it’s raining, drops of water sweep in, like a mist, and it makes her feel as though she’s arrived

somewhere real and tangible and alive, so far from a carpeted airport terminal you feel like you’re in another world.

Her friends from up there never come down here. They’re afraid of getting killed, or worse.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with these people,” she complained to her father as he watched her pack the night before. “It’s

extraordinary, really. They go to Singapore, to Turkey, to Peru! But Colombia is too dangerous.”

Her father didn’t say anything, because he’s as guilty as they are, absent from her trips for over a decade.

“They’ll go down,” he finally contributed. “They’ll fall in love with a Colombian, and then they’ll have to,” he added with

a laugh, a laugh that tried to tell her it’s okay that once again she’s going without him.

She could sense his unease, could see it in his worried blue eyes, in his tall lanky frame that tonight was coiled tight,

his legs crossed, his arms crossed, sitting on her bed, trying to look nonchalant but swinging his foot incessantly, making

her nervous as hell.

“Try and use your time there wisely, Gabby,” he said. “Think about where you want to be a year from now. You have to make

a plan.”

Gabriella wanted to say that maybe it could be wise

not

to have a plan for a change, that plans interfered with creativity, but he interrupted her thoughts before she could put

them into words.

“And remember, I don’t want you driving alone, okay?” he said for the third time that evening. “And I don’t want you walking

around without Edgar,” he added, referring to her grandmother’s bodyguard. “And I want you to call me as soon as you land

and as soon as you get into Nini’s house. And I want you to keep that cell phone on at all times.”

“Daddy!” she finally exclaimed, exasperated. “Daddy,” she repeated softer, picturing him alone in their big house for a whole

month while she’s gone. “It’ll be okay. Nothing bad’s gonna happen,” she said placatingly, even though they both know bad

things can happen, bad things

have

happened.

But they happen to other people, not to her.

“I’ll be fine,” she added, sitting next to him on the bed, her dark, curly head close to his straight, blond mane. She ran

her fingers through his soft hair, twirling it at the nape of his neck, like she used to do when she was a little girl. “I’ll

be fine.”

Thinking of him now reminds her she has to call. A quick call.

“Two dollars and fifty cents a minute,” he’s reminded her a dozen times, because she is a fiend with her cell phone and her

text messages, and roaming fees to Colombia are outrageous, even for someone like him. When he answers, she speaks rapidly,

almost furtively, and he laughs just to hear her voice, because she always makes him laugh. And she laughs, too, happy that

he’s finally happy, that she’s arrived, that she’s fine, and that now she can embrace her days here without guilt.

Tonight it smells like rain, and the wind carries a whiff of sugarcane from the refineries in the valley. She breathes deeply,

taking in the burned, bittersweet smell, a smell most people can’t stand but whose familiarity she embraces. For a moment,

she feels physically lighter, feels the weight of her worries loosening their grip on her: what she wants, what she’s supposed

to do, who she’s supposed to be in six months when she graduates.

“Extraordinary.” That’s what they say about her. Her father, her grandparents, her teachers. They say it to her face, and

they talk about it when they don’t think she’s listening, ticking off the long list of potentials she could be. And if she

could get off the treadmill of endless expectations, maybe she could focus for a moment, but she never seems to have the time.

She looks out at the airstrip from the open window and gets the strongest urge to go out there and run into the darkness,

caution be damned, beyond the point where the airport lights end and the planted fields abruptly begin. She suddenly remembers

one summer afternoon, several years ago, when they parked the car on a dirt road and climbed up to a grassy knoll, where her

cousin Juan Carlos and she watched the sun set and the planes take off. The sky was stunning, with sweeps of orange and purple

and pink, and for a few minutes, they felt like the only people alive, the only ones who knew that such beauty existed and

was available free for them.

They stayed there until it was dark, and by the time they got home, it was nine and Nini was so mad.

She’ll be here for four weeks. Same as it’s been every Christmas, for as long as she can remember.

“Gabriella,” says the immigration agent, looking at her American passport, then speaking to her in Spanish. “Razón por la

cual viaja?”

“Vacaciones,” she replies.

He grunts. Thumbs through the passport. Stamps. Then finally looks up at her. Unsmiling but polite, and yes, gratified that

she’s there, a foreigner in a city that discourages foreigners.

“Bienvenida a Cali, Gabriella,” he says and hands her the passport.

Outside, Cristina Gómez waits. She waits and she frets, her perfectly glossed lips pursed, both arms clutching her handbag,

even though Edgar is standing right by her side. Cristina hates airports in general and this airport in particular. Because

it’s hot and chaotic. Because the cement outside of customs is always slick with rain and aguardiente and trampled fruit.

Because hordes of people, wound tightly together like spools of yarn, strain against each other to get a glimpse of the arrivals

through the tinted glass, their shouts of recognition blending with shouts of drunkenness as bottles are passed back and forth,

back and forth over her head.

Because she’s petite and claustrophobic and always thinks she’ll suffocate while she waits, and because it invariably reminds

her of the accident. For years, she couldn’t bring herself to come here. Regardless of who was arriving, she would dispatch

Edgar and go out someplace else—never staying home—so as to dispense with any semblance of waiting. But when Gabriella turned

ten and started to fly alone, she took it as her cue to take responsibility again.

Before that, Marcus would bring Gabriella for a week or two, in a gesture of solidarity with Cristina, even though they lived

in Los Angeles and the trip was long and involved two flights. If Cristina had a soft spot for her son-in-law before the accident,

she became his fiercest advocate afterward, supporting him through what she would teasingly refer to as his “dissolute lifestyle”—one

girlfriend after the other. He never remarried, he didn’t have any more children. She had never demanded that he give her

time with Gabriella, but he had understood it was the correct thing to do, and she was grateful. As the years passed, he stopped

coming altogether. But he never denied her Christmas, even the few times Gabriella herself had begged not to come because

she was dating one boy or another.

Eleven years she’s come to pick this child up. Always at this time, from this gate, from this flight; the same flight her

mother used to take. The wait takes place outside, and it involves throngs of people, all anxiously leaning against the railing

that leads to the exit door. They hold signs, toddlers with flowers and gifts, cameras. Moisture sticks to her skin, and she

feels something wet on her face. Panicking, she swats her hand against her cheek, then stops, feeling foolish as she realizes

it’s her own perspiration damaging her matte makeup.