Television's Marquee Moon (33 1/3) (10 page)

Read Television's Marquee Moon (33 1/3) Online

Authors: Bryan Waterman

Glitter was alive enough in ’74 that Wayne County, Richard Robinson, and others held a panel on the topic for industry insiders that October.

148

KISS’s first album had appeared earlier that year; the Queens band had taken original inspiration from the Dolls and other New York glitter acts. But KISS, unlike the Dolls, offered a pronounced distance between their performance on and off stage. The Ramones, like Richard Hell, created characters for themselves that were supposed to break down the barrier between public and private personae. They saw the writing on the Dolls’ wall: Johnny Ramone, who had worn spandex and glitter with the best of them, agreed to go with the band’s biker jacket look: pre-Ramones, he recalled, “I had on silver lamé pants and a leather jacket with leopard-print fur around the collar. How you gonna get people coming to the shows like that?” It might fly in New York or LA, but they “wanted every kid in middle America to be able to identify.”

149

They settled on jeans and T-shirts, sneakers and shades, a more cartoonish version of the look Hell was after. “We were glamorous when we started, almost like a glitter group,” Dee Dee later said. “A lot of times Joey would wear rubber clothes and John would wear vinyl clothes or silver pants. We used to look great, but then we fell into the leather-jacket-and-ripped-up-jeans thing. I felt like a slob.”

150

As the scene continued to snowball, and with a dozen summer performances behind her, Patti Smith co-headlined Max’s with Television for ten nights in August and September. “For anybody who cares about What’s Happening,” Danny Fields wrote in the

SoHo Weekly News

, Smith and Television were “not-to-be-missed, and both of them together makes for the ultimate musical billing of the season, if not the year.”

151

Earlier in the summer Fields had raved about “our beloved and fantastic Television,” whose show at Club 82 didn’t “remind anyone of anything else, because they are so very unique.”

152

Early Television shared with contemporaries like the Ramones a preference for short songs, but they also aimed for a kind of sophisticated engagement with pop music history that set them apart from some of the other downtown bands. One early press release aimed to convey their distinction:

TOM VERLAINE — guitar, vocals, music, lyrics: Facts unknown. RICHARD HELL — bass, vocals, lyrics: Chip on shoulder. Mama’s boy. No personality. Highschool dropout. Mean. RICHARD LLOYD — guitar, vocals: bleach-blond — mental institutions — male prostitute — suicide attempts. BILLY FICCA — drums: Blues bands in Philadelphia. Doesn’t talk much. Friendly. TELEVISION’s music fulfills the adolescent desire to fuck the girl you never met because you’ve just been run over by a car. Three minute songs of passion performed by four boys who make James Dean look like Little Nemo. Their sound is made distinctive by Hell’s rare Dan Electro bass, one that pops and grunts like no model presently available, and his unique spare patterns. Add to this Richard Lloyd’s blitzcrieg chop on his vintage Telecaster and Verlaine’s leads alternately psychotic Duane Eddy and Segovia on a ukelele with two strings gone. Verlaine, who uses an old Fender Jazzmaster, when asked about the music said, “I don’t know. It tells the story. Like ‘The Hunch’ by the Robert Charles Quintet or ‘Tornado’ by Dale Hawkins. Those cats could track it down. I’ll tell you the secret.”

153

Another Xeroxed, self-authored press release from the period describes the band as a “peculiarly successful melding of the Velvets, the Beatles, the everly brothers [

sic

], and Kurt Weill.”

154

Working out early rough spots on stage, Television gained local notoriety for time spent tuning and for inconsistent performances.

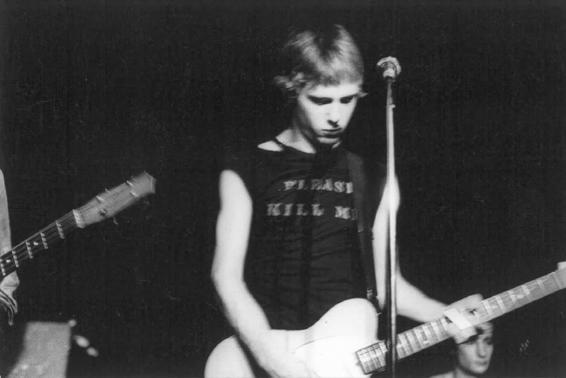

FIGURE 3.2

Richard Lloyd onstage at Max’s Kansas City, 28 August 1974. Photo courtesy of Michael Carlucci Archives

Television also drew attention for its carefully crafted image, especially the torn clothing. On at least one night at Max’s, when Television took the stage, Richard Lloyd wore a torn black T-shirt Hell had designed, with the words “Please Kill Me” stenciled in capital letters across the front (fig. 3.2). Though some scenesters would later recall Hell wearing the shirt, he claims he never worked up the nerve. (When Lloyd first wore the shirt at Max’s, Hell was wearing a long-sleeved satin shirt with one shoulder torn away.) Lloyd says he volunteered to wear the Please Kill Me shirt only to be deeply unsettled when a few fans at Max’s approached him with “this really psychotic look — they looked as deep into my eyes as they possibly could — and said, ‘Are you serious?’”

155

If some fans seemed murderous, others seemed suicidal. According to Verlaine, interviewed in early ’75,

There’s this group of people that are over forty, ex-suicide types that come up to us after every gig we play, no matter where or how little advertised it was, and they just look like they’ve seen Jesus. I don’t know who they are or where they come from but they’re always there, just gaping … may be just listening to us is like jumping off a bridge, it’s just as good.

156

This self-conscious, proto-punk nihilism was at the core of early Television songs like “I Don’t Care” (later retitled “Careful”) or Hell’s most popular tune, “Blank Generation.” On the latter, Hell updated the chorus of an old Beatsploitation novelty song by Rod McKuen. Instead of singing “I belong to the Beat Generation / I don’t let anything trouble my mind / I belong to the Beat generation / and everything’s going just fine,” Hell offered the wittier: “I belong to the Blank Generation / And I can take it or leave it each time. / Well, I belong to the _______ Generation / And I can take it or leave it each time. / Take it!” On the second run through the chorus the “blank” becomes a moment of silence when Hell withholds the word and the band stops playing, emphasizing the void. As in other Television songs, the song puns elaborately, from the opening line (“I was saying lemme outta here / Before I was even born”) to the play on “Take it!” which led directly to Verlaine’s solo. The positive impulse to “Take it!” underscores Hell’s long-standing argument that by “blank” he intended to convey possibility: “It’s the idea that you can have the option of making yourself anything you want, filling in the blank,” he told Lester Bangs later in the decade.

157

But Bangs and others still read “blank” as abjection; when Malcolm McLaren borrowed Hell’s signature style to create the Sex Pistols, he demanded the band rewrite Hell’s anthem. Their version was “Pretty Vacant.”

158

Following the Max’s gigs, Smith revised her profile of the band for the October

Rock Scene

, in ways that suggest band members’ collaborations with her in creating a rapidly consolidating mythology. In the new piece, Smith casts Hell as a “runaway orphan” from Kentucky, “with nothing to look up to.” He and Verlaine, she writes, “done time in reform school” before running away. Lloyd “done time in mental wards,” a detail that plays on her earlier depiction of the band as borderline insane. (“When I was a little kid, I always wanted to be crazy,” Lloyd added at a later date, picking up on the theme.

159

) Billy Ficca, as Smith describes him, had “been ‘round the world on his BSA,” a real bad-ass. Though most of these elements have some grounding in documentable fact her spin consistently tips toward hyperbole. Despite her insistence that Television “are not theatre” — that they are the antithesis of camp and cabaret — it’s clear that their performance is still an act, but one she’s willing to buy and to help perpetuate.

In addition to cultivating the band’s mystique, Smith offers here a more mature consideration of the band’s relationship to rock history than she had earlier. She recognizes in Television’s sound a tension between revolution and revision, between an attempt to break it up and start again, on one hand, and the ways in which these boys inherit the mantle of Chuck Berry, Dylan, the Stones, the Yardbirds, Love, and the Velvets, on the other. Riffing extensively on the band’s name, Smith asserts that Television is

real

, unmediated, a point underscored by the fact that they can only be experienced via live shows, not on studio recordings, and that their image is authentic. Smith’s difficulty articulating the authenticity/artificiality dynamic in Television’s early act suggests an ambivalence toward Warholism that would become more pronounced on the scene over time. “Television will help wipe out media,” she declares at one point. Not satisfied with that formulation she expands on it, framing the band as an “original image,” something like live television: raw, unpredictable, without rules. Instead of “Hollywood jive,” she wants something “shockingly honest. Like when the media was LIVE and Jack Paar would cry and Ernie Kovacs would fart and Cid Cesar would curse and nobody would stop them ‘cause the moment was happening it was real. No taped edited crap.”

160

Part of what had been lost for Smith in mainstream rock’s studio wizardry and radio-friendly accessibility was youthful sexual energy, the thrust of Elvis’s pelvis, Jagger’s cocky strut, the moves that made early TV execs and some viewers (like her father) uncomfortable. For her, Television’s power rested in what she identified as a sort of “high school 1963” sexuality: “Television is all boy,” she’d written in the

SoHo Weekly News

, and for

Rock Scene

she elaborates at length. Finding them “inspired enough below the belt to prove that SEX is not dead in rock & roll,” she revels in lyrics “as suggestive as a horny boy at the drive in”: songs with titles like “Hard On Love,” “One on Top of the Other,” and “Love Comes in Spurts.” She characterizes the band members as variations on a bad boy persona, as if Brando and his gang had just rolled onto the Bowery, set on terrorizing the locals and making off with the nicest of the nice girls. Hell reminds her of

Highway 61

–era Dylan and is “male enough to get ashamed that he writes immaculate poetry”; Lloyd, “the pouty, boyish one,” plays “highly sexually aware guitar,” “jacks off” on his instrument, even. In her earlier piece she’d identified “confused sexual energy.” Though she doesn’t say it outright, the implication here is that, unlike the Dolls, these aren’t straight kids dressed up like girls or queers. Television “play like they make it with chicks” and “fight for each other” like street kids in a rumble, “so you get the sexy feel of heterosexual alchemy when they play.” Verlaine, who “has the most beautiful neck in rock ‘n’ roll,” is a “guy worth losing your virginity to.”

161

Smith’s characterizations play on early Television’s paradoxes. They are both highly sexual

and

evocative of virginity or innocence; they are tough guys

and

likely to get beat up by tough guys. Her piece suggests that ’50s nostalgia expressed a desire for a pre-Vietnam conflict America, but also a desire for adolescent regression, a return to the pleasures and dangers of being a teenager. Part of what she taps into resonates with with

Grease

on Broadway, or the ubiquity of the Fonz. But she also identifies something larger than mainstream America’s simplistic ’50s revival. Here, just as punk is starting to stir, she pinpoints what will be one of its most fundamental characteristics, moving across the range of sounds and styles that will be classified as punk in decades to come: Above all else, punks will be “[r]elentless adolescents.” She invokes the prototypical Bowery Boys to nail down the point: Television are latter-day “Dead end kids.” When Smith comes to the end of this piece, she replaces the collective emphasis on rock seraphim with a vision of Verlaine as a singular “junkie angel.” She points to “the outline of his hips in his pants,” and then imagines that “he’s naked as a snake,” Adam and Satan all in one.

162

Of the just more than two dozen nights Television played in 1974, only nine of those dates were at CBGB’s, fewer shows than they played in August and September at Max’s with Patti Smith’s group. When Fields wrapped up the year for

SoHo Weekly News

, the Max’s appearances with Patti received his nod for local show of the year. Between that run’s conclusion and the end of November, Television hunkered down to rehearse, hoping to follow Smith’s example and cut an independent single. CB’s plowed ahead without them, maintaining its bluegrass credentials; in between some new music shows featuring the Ramones, the club played host repeatedly to a group called the Hencackle String Band.