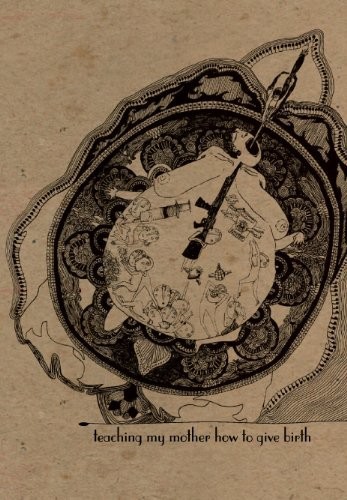

Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth

Read Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth Online

Authors: Warsan Shire

Tags: #Warsan, #Africa, #Poetry, #Shire, #migration, #Warsan Shire, #Somalia

mouthmark series

Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth

by Warsan Shire

literary pointillism on a funked-out canvas

Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth

mouthmark series (No. 10)

Produced in the United Kingdom

Published by the mouthmark series, 2011

a pamphlet series of flipped eye publishing

All Rights Reserved

Cover Design by Effi Ibok

Series Design © flipped eye publishing, 2006

First Edition

Copyright © Warsan Shire 2011

Print ISBN: 978-1-905233-29-8

Mother, loosen my tongue or adorn me with a lighter burden.

— Audre Lorde

Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth

I have my mother’s mouth and my father’s eyes; on my face they are still together.

What Your Mother Told You After Your Father Left

I did not beg him to stay

because I was begging God

that he would not leave.

Your Mother’s First Kiss

The first boy to kiss your mother later raped women

when the war broke out. She remembers hearing this

from your uncle, then going to your bedroom and lying

down on the floor. You were at school.

Your mother was sixteen when he first kissed her.

She held her breath for so long that she blacked out.

On waking she found her dress was wet and sticking

to her stomach, half moons bitten into her thighs.

That same evening she visited a friend, a girl

who fermented wine illegally in her bedroom.

When your mother confessed

I’ve never been touched

like that before

, the friend laughed, mouth bloody with grapes,

then plunged a hand between your mother’s legs.

Last week, she saw him driving the number 18 bus,

his cheek a swollen drumlin, a vine scar dragging itself

across his mouth. You were with her, holding a bag

of dates to your chest, heard her let out a deep moan

when she saw how much you looked like him.

Things We Had Lost in the Summer

The summer my cousins return from Nairobi,

we sit in a circle by the oak tree in my aunt’s garden.

They look older. Amel’s hardened nipples push through

the paisley of her blouse, minarets calling men to worship.

When they left, I was twelve years old and swollen

with the heat of waiting. We hugged at the departure gate,

waifs with bird chests clinking like wood, boyish,

long skirted figurines waiting to grow

into our hunger.

My mother uses her quiet voice on the phone:

Are they all okay? Are they healing well?

She doesn’t want my father to overhear.

Juwariyah, my age, leans in and whispers

I’ve started my period

. Her hair is in my mouth when

I try to move in closer–

how does it feel

?

She turns to her sisters and a laugh that is not hers

stretches from her body like a moan.

She is more beautiful than I can remember.

One of them pushes my open knees closed.

Sit like a girl

. I finger the hole in my shorts,

shame warming my skin.

In the car, my mother stares at me through the

rear view mirror, the leather sticks to the back of my

thighs. I open my legs like a well-oiled door,

daring her to look at me and give me

what I had not lost: a name.

Maymuun’s Mouth

Maymuun lost her accent with the help of her local Community College. Most evenings she calls me long distance to discuss the pros and cons of heating molasses in the microwave to remove body hair. Her new voice is sophisticated. She has taken to dancing in front of strangers. She lives next door to a Dominican who speaks to her in Spanish whenever they pass each other in hallways. I know she smiles at him, front teeth stained from the fluoride in the water back home. She’s experiencing new things. We understand. We’ve received the photos of her standing by a bridge, the baby hair she’d hated all her life slicked down like ravines. Last week her answering machine picked up. I imagined her hoisted by the waist, wearing stockings, learning to kiss with her new tongue.

Grandfather’s Hands

Your grandfather’s hands were brown.

Your grandmother kissed each knuckle,

circled an island into his palm

and told him which parts they would share,

which part they would leave alone.

She wet a finger to draw where the ocean would be

on his wrist, kissed him there,

named the ocean after herself.

Your grandfather’s hands were slow but urgent.

Your grandmother dreamt them,

a clockwork of fingers finding places to own–

under the tongue, collarbone, bottom lip,

arch of foot.

Your grandmother names his fingers after seasons–

index finger, a wave of heat,

middle finger, rainfall.

Some nights his thumb is the moon

nestled just under her rib.

Your grandparents often found themselves

in dark rooms, mapping out

each other’s bodies,

claiming whole countries

with their mouths.

Bone

I find a girl the height of a small wail

living in our spare room. She looks the way I did when I was fifteen

full of pulp and pepper.

She spends all day up in the room

measuring her thighs.

Her body is one long sigh.

You notice her in the hallway.

Later that night while we lay beside one another

listening to her throw up in our bathroom,

you tell me you want to save her.

Of course you do;

This is what she does best:

makes you sick with the need

to help.

We have the same lips,

she and I,

the kind men think about

when they are with their wives.

She is starving.

You look straight at me when she tells us

how her father likes to punch girls

in the face.

I can hear you in our spare room with her.

What is she hungry for?

What can you fill her up with?

What can you do, that you would not do for me?

I count my ribs before I go to sleep.

Snow

My father was a drunk. He married my mother

the month he came back from Russia

with whiskey in his blood.

On their wedding night, he whispered

into her ear about jet planes and snow.

He said the word in Russian;

my mother blinked back tears and spread her palms

across his shoulder blades like the wings

of a plane. Later, breathless, he laid his head

on her thigh and touched her,

brought back two fingers glistening,

showed her from her own body

what the colour of snow was closest to.

Birds

Sofia used pigeon blood on her wedding night.

Next day, over the phone, she told me

how her husband smiled when he saw the sheets,

that he gathered them under his nose,

closed his eyes and dragged his tongue over the stain.

She mimicked his baritone, how he whispered

her name– Sofia,

pure, chaste, untouched.

We giggled over the static.

After he had praised her, she smiled, rubbed his head,

imagined his mother back home, parading

these siren sheets through the town,

waving at balconies, torso swollen with pride,

her arms fleshy wings bound to her body,

ignorant of flight.

Beauty

My older sister soaps between her legs, her hair

a prayer of curls. When she was my age, she stole

the neighbour’s husband, burnt his name into her skin.

For weeks she smelt of cheap perfume and dying flesh.

It’s 4 a.m. and she winks at me, bending over the sink,

her small breasts bruised from sucking.

She smiles, pops her gum before saying

boys are haram, don’t ever forget that

.

Some nights I hear her in her room screaming.

We play Surah Al-Baqarah to drown her out.

Anything that leaves her mouth sounds like sex.