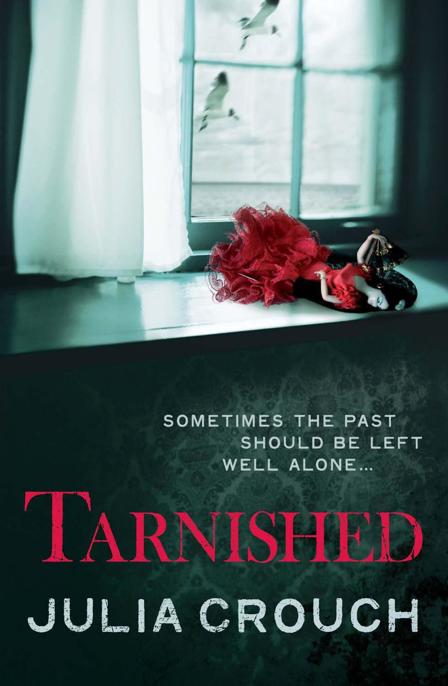

Tarnished

Praise for Julia Crouch:

‘Another terrific page-turner’

Guardian

‘Brilliant, truly chilling’ Sophie Hannah

‘A tale of slow-burning suspense . . . Crouch deftly avoids the obvious and builds up a very convincing air of menace’

Daily Express

‘Very enjoyable; expertly paced and cleverly ambiguous’

Daily Telegraph

‘A brilliant debut novel . . .

Cuckoo

is a riveting and spooky story that keeps your eyes locked in the page, and leaves you feeling shaken and out of sorts’

Heat

‘An entertaining rollercoaster of a read . . . I devoured it in hours’

Stylist

A tale of slow-burning suspense, but Crouch, whose debut novel this is, deftly avoids the obvious and builds up a very convincing air of menace in her extremely well-described portrait of famiky life becoming frayed at the edges with fatal results’

Daily Mail

‘Hot on Sophie Hannah’s heels’

Mirror

‘A gripping and thrilling debut – you really don’t want it to end’

Sun

Copyright © 2013 Julia Crouch

The right of Julia Crouch to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an eBook by Headline Publishing Group 2013

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ePub conversion by Avon DataSet Ltd, Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire

eISBN: 978 0 7553 7808 1

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.headline.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

Also by Julia Crouch and available from Headline

Cuckoo

Every Vow You Break

About the Book

Mild-mannered Peg has never asked too many questions about her unusual upbringing: her absent father; her deceased mother; her bed-ridden aunt. Peg can’t remember much from before the age of ten, but she’s happy to fill in the gaps with fond memories of home-cooked dinners and walks along the seaside.

But when, all grown up, Peg discovers she had an uncle who died many years ago, the holes in her childhood memory start to trouble her. Yet as the skeletons come tumbling out of the family closet and the past begins to reveal itself, Peg starts to wonder whether her youthful lack of curiosity might not have been a good thing. A very good thing indeed . . .

To my family (no relation)

1992: Beachcomber

It was just about dawn, but the moon still hung, enormous, above the sea. The lowest spring tide of the year was due in an hour, and Colin Cairns had been looking forward to it like a child waiting for Christmas.

He crunched down the shingle, over the extraordinary collection of cuttlefish bones the tide had brought in at its highest point the night before. It always made him wonder where they came from when they were thrown up like that: was there a mass cuttlefish murder event, an orgy of tentacles entwining round necks? Did cuttlefish even have necks? He stopped and made a note in the little pad he carried with him, carefully writing the question in capital letters.

A wind blew in from the east, whipping loose tangles of kelp and net over the sand-and-mudflats like tumbleweeds in a Western. Glad both of his cagoule and the balaclava his mum had knitted for him, he pressed on, lugging his equipment down the slope towards the mud, which, today being a Proxigean Spring Tide, stretched on almost as far as he could see. Only a tiny hint of movement on the horizon suggested that there might be any water at all out there. All that mud! All that sea-bottom to explore! As he reached the end of the shingle his joy overflowed into an awkward little dance and he skipped round the straggles of seaweed and worm casts towards The Street.

There was no better place for detecting than The Street. Even on a normal day, the ancient strand of clay and shingle took you right out, so far that you felt like you were that old King Canute, or Jesus even, walking on the water. Today it was so far that Colin reckoned he could walk out to the horizon as far as the Maunsell sea forts, whose history and facts he knew by heart.

But that wasn’t what he was there for this morning. He pulled his big headphones up over his balaclava’d ears, switched on his battery pack and started on his long walk outwards, sweeping his detector from side to side as he went.

From his study of tidal flow in the area, Colin had come to the conclusion that, if you wanted a good find, The Street was the place to go. Created by two currents converging, it had a tendency to catch interesting things. So far, in his hours of splashing around its edges with his detector, Colin’s most valuable discoveries included several coins he thought to be Roman, a gold ring that probably wasn’t all that old, something circular and rusted that he liked to think was a Saxon neck adornment, and part of some sort of helmet. He had a private museum in his bedroom where he displayed his prizes, each labelled with the date of discovery, his own name as the discoverer, and his estimate of the provenance of the item. He spent a good deal of time in the library, looking things up.

His odder finds included a payphone coin box (sadly emptied), a set of dentures and the remains of a corset with metal stays. He had also found the skeleton of what he reckoned was a dolphin, as well as a leathery, beached angler-fish. Once he had come across the corpses of fifteen giant ray fish – dismembered heads, long, whippy spines, chomped fins.

Someone must have been having a feast, was what he had thought.

He took photographs with the Kodak Instamatic he kept in his rucksack. He always photographed what he found out here. It was important to keep a record.

Absorbed in his task, listening intently for a change in the crackle, buzz and beep of his detector, his eyes going blurry with the effort of keeping sharp, Colin didn’t at first notice the sea fog rolling in on the wind. He had travelled out for what he reckoned was about three-quarters of a mile and things were going well. He had already stopped three times, digging up five ancient nails that he imagined might have come from a medieval boat, three pound coins in a waterlogged leather purse and a beer can of a type he didn’t already have in his collection. He had also nearly stepped in, then photographed, a wobbling jellyfish that must have been over two feet across.

Then he realised that he could no longer clearly see the ground at his feet. He stopped and cleaned his glasses, but that wasn’t it. For an alarming second he thought he had got his timing wrong and the tide, which he had thought was going out, had in fact turned. If that was the case, he wouldn’t get back in time to cross the shore-end dip that filled in early, and he would be stranded: cut off by the incoming tide, like the sign on the promenade warned.

But then he looked around and realised that the twinkling lights of home were now hidden, and his destination – the tip of The Street as it emerged from the still-outgoing tide – was also not to be seen.

He lifted his headphones from his ears and listened.

While the fog cloaked almost everything from view, it seemed to have brought the sound of the sea closer, as if it were lapping at his feet rather than the murk.

It was off-putting – eerie, even.

Colin thought perhaps he should return to the shore and the flask of tea he had hidden behind a beach hut.

But the pull of The Street – the fact that he would, very soon, be stepping on ground which, because of the lowness of the tide, people touched perhaps only once every couple of years – was too strong to resist. So instead, to get his bearings, he walked sideways, to the very edge, just to confirm that the sea was indeed still going out.

He stood and waited for five minutes as he watched the water recede from the wet mud and gravel, travelling out beyond an old metal post stuck in the ground. He wondered as he waited how old it might be. Perhaps it had been used by the Saxons to tie their boats to when they used The Street as a landing point before the harbour was built. Satisfied that the tide was still outgoing, he put his headphones on again and resumed his journey, keeping the water just to his right.

Apart from another metal post, he didn’t find anything in the next five hundred or so yards. Visibility improved: the fog was slightly thinner out here. He stopped and cleaned his glasses again, pulling his T-shirt out from underneath all his layers to polish them. As he slid the frames back up onto his face, he caught sight of something interesting, a lumpish shape at the water’s edge, about ten feet away.

Thinking perhaps it was a ball, possibly kicked over-enthusiastically by a sailor enjoying a little R and R on a warship somewhere out there, Colin wandered over to take a look. He turned the thing over with his wellington boot, and, not quite believing what he saw, he laid his detector on the drier ground to his left and squatted to take a closer look.

A tiny crab scuttled in one of the black holes that once would have been eyes looking back up at him. What remained of her face told him that she had probably been quite pretty, and she had lovely blond hair. Long. It made him sad to see her there, and he knew he should do something about her.