Tango (7 page)

Authors: Mike Gonzalez

para arrancarla a pedazos

en una queja postrera

,

¡como si en vos gimiera

mi propio corazón! . .Â

.

¡Corazón! . . .

Que lanzás al viento

con cada suspiro

el hondo lamento

de tu sentimiento

,

y en cada respiro

crece tu emoción . .Â

.

Cuando en la tristeza

tu canción se abisma

,

¡sos el alma misma

de mi bandoneón! . .Â

.

Bandoneon / You cast to the wind / Through your hundred wounds / That eternal lament / And with each breath / You restore a hundred lives / To weep the better! / With the harmonies that bleed out from you / or the quiet tears / you are the faithful cure / for my own love!

When your lungs expand / and issue a thousand songs / the soul of your harmony / your sad song feels / like my very own . . .

And I squeeze you in my arms / to draw out the song little by little / in a long complaint / As if your sound / were the trembling of my own heart

.

My heart! . . . / You cast into the wind / with every sigh / the deep feelings / of sorrow / and the emotion grows more intense / with

every breath . . . / and when your song / sinks into sadness / you are the very soul / of my bandoneon

.

(âBandoneón' â José González Castillo, n.d.)

The arrival of the bandoneon produced an immediate change in the dance. The guitar and flute had accompanied the fast, dramatic and erotic steps of the original dance â the âruffian's dance' (the

tango rufianesco). 7

7

Its frankly sexual gestures and movements shocked and repelled the respectable middle clases, yet they were not immune to the impact of the music, nor to its seductions. The way in which the bandoneon was played added drama and passion to the sound of tango, but it was slower and more sensual, its undulations more melancholy and provocative. And its arrival coincided with tango's first tentative steps towards the new elegant cafés and cabarets around the well-lit streets of the city centre, places like Lo de Hansen or El Velódromo, whose names would soon appear in tango lyrics and circulate among enthusiasts. The music itself began to become acceptable in the more elegant, if slightly more liberal salons, though dancing was still forbidden in most of them, and a new generation of performers found audiences (and wages) beyond the barrio when they gave exhibitions in the more adventurous venues. Rosendo Mendizábal was an accomplished pianist whose âEl Entrerriano' became one of the best known of the new tango concert pieces â music, in other words, to be listened rather than danced to. Only the most daring middle-class woman around 1900 would be prepared to venture into the areas near the docks in the afternoon to seek out the handsome young men who offered themselves as dance partners. But they could enthusiastically attend the exhibitions given by the new generation of professional dancers, chief among them Ovidio José Blanquet, known as âEl Cachafaz', âthe Insolent Kid'.

Tango was creeping across the border, or at least gaps had been opened that allowed some communication between the two worlds of the city. The marginal quarters remained, from a middle-class point of view, places of danger and forbidden pleasure. And the estimated 20â30,000 prostitutes in Buenos Aires confirmed both the availability and the variety of the erotic. Traffic was, of course, predominantly one-way. If the women of the middle class approached in the afternoon light, their husbands slipped into the port area under cover of darkness. But tango's best known artists now made increasingly frequent incursions into the gleaming halls of the city centre. And in the theatres (attended by and large by the middle class) the world of tango began to be referred to in the comic operas (

sainetes

) and musicals (

zarzuelas

) that were popular at the time. It is true that the theatrical representation of the immigrant at the turn of the century was still largely comic, grotesque and caricatured â but tango music too was played in the same theatres. Though it might be publicly derided and reproved by the bourgeoisie, their fascinated response to its seductions made that rejection hypocritical at best.

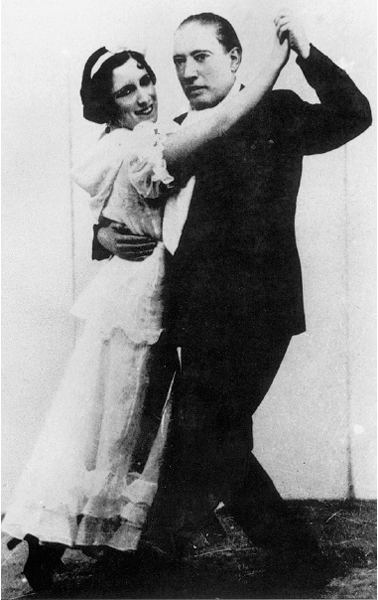

El Cachafaz.

Tango was making its way into the bourgeois world, albeit slowly and hesitantly. The rite of passage was largely completed during the first decade of the twentieth century. But it was a process fraught with contradictions. The numbers of immigrants had leapt once again in the 1890s, fuelling the anxieties of the middle classes. The growing working class was beginning to organize and forge the early trade unions, radical in their predominantly anarchist ideology and increasingly militant in their actions. The discontent at living and working conditions was rising, reaching a critical point in the 1907 rent strike in the

conventillos

, when, for the first time, the human beings pressed into the overcrowded shacks and shanties of the dock districts took on their landlords. It was commemorated in the

sainete

âLos inquilinos' (The Tenants), which included a tango with the same title:

Señor intendente

,

los inquilinos

se encuentran muy mal

se encuentran muy mal

pues los propietarios

o los encargados

nos quieren ahogar

.

Abajo la usura

y abajo el abuso

;

arriba el derecho

y arriba el derecho

del pobre también

.

Mr Mayor / the tenants / are in a very bad way / in a very bad way / because the landlords / or their agents / are drowning us. / Down with usury / down with their abuses / long live justice / long live justice / and long live the rights / of poor people too. 8

8

The inclusion of these issues in the popular music of the day testifies to the way in which the newly emerging tango lyrics had moved from the simply provocative or plainly obscene to becoming a narrative of the life and experience of the barrios â its housing, its resistance, its desires and frustrations, and to a very limited extent, its experience of work. It remained the voice of the barrios, its streets and communal life. And it retained as its central character the isolated young man, living the life of the streets, whose strutting and preening in the dance conceals a deeper sense of continuing marginality and exclusion.

As he protects himself with a facade of steps that demonstrate perfect control [the male tanguero] contemplates his absolute lack of control in the face of history and destiny.

9

Women are very rarely heard in tango's early lyrics. There were some who made their name in this world despite their suppression â singers, dancers and madams. But it was always a dance led by men, danced with other men or women, but only very rarely by women with one another. The game of seduction it enshrined was not conducted between equals. When the first women tango singers emerged at the beginning of the Golden Age, they dressed in men's clothing.

But at this time, the majority of tango writers and musicians were part-time artists whose main source of income was elsewhere. AgustÃn Bardi worked in a shop, Vicente Greco sold newspapers, Juan Maglio was a mechanic â though they would later find an adequate living from tango. But first, tango would need to win the battle for acceptance.

And for that to happen, it had first to wrestle with the suspicion that tango still aroused and the very different visions of the dance.

The room fills with happy people; everywhere one hears phrases that could make a vigilante blush. In the background a group of petty criminals from the barrios with improvised disguises, in the theatre boxes handsome men and even more handsome girls. Suddenly the orchestra begins a tango and the couples begin to form. The china and compadre join together in a fraternal embrace, and then the dance begins, in which the dancers show such an art that it is impossible to describe the contortions, dodgings, impudent steps and clicking of the heels the tango causes.

The couples glide energetically to the beat of the dance, voluptuously, as if all their desires are placed in the dance. In the background, the people form groups to see figures done by a girl from the suburbs, who is proclaimed the mistress without rival in this difficult art, and the crowd applauds these

prodigious figures, drawing back scandalized when the dancer's companion says âGive me the pleasure, my little “china”'.

10

The Scottish writer Robert Cunninghame Graham, however, seemed slightly more shocked by what he saw.

They were so close to each other that the leg of the carefully pressed trouser would disappear in the tight skirt, the man holding her in such a close embrace that the hand ended up by the woman's face. They gyrated in a whirlwind, bending down to the floor, advancing the legs in front of each other while turning, all of this with a movement of the hips that seemed to fuse the impeccable trousers with the slitted skirt. The music continued more tumultuously, the musical times multiplied until, with a jump, the woman would throw herself into the arms of her partner, who would put her back on her feet.

11

Clearly such antics would horrify the ladies of Palermo and reinforce their resistance to the tango's incursions into their lives. Conservative writers like Leopoldo Lugones and Manuel Galvez looked upon the tango with barely disguised racial arrogance: âthe product of cosmopolitanism, hybrid and ugly music . . . a grotesque dance . . . the embodiment of our national disarray'.

12

There were persistent attempts to close down the brothels, and eventually new ordinances to control the bordellos were passed in 1915. And the wealthy districts were becoming increasingly nervous about the rise of anarchist groups which they associated with prostitution and criminality.

In the end, their resistance was to no avail. Tango won its right to exist, but only after Tangomania hit Paris.

3

TANGO GOES TO PARIS

PLACES OF PLEASURE

At the Universal Exhibition of 1900, when Paris gathered the products of the new and exciting modern world, from automobiles to electricity, John Philip Sousa's band played ragtime music for the middle class of Paris. Two years later, in 1902, âLes Joyeux Nègres' (The Cheerful Negroes), a show featuring The Little Walkers at the Nouveau Cirque, caused a sensation when it introduced the cakewalk to its audiences. In 1906, Debussy composed his (unfortunately named) âGollywog's Cakewalk', while in the following year Picasso and Matisse both produced iconic paintings (

Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon

and

Blue Nude

respectively) which celebrated the art of Africa, which they had seen at the famous exhibition of African Art in Paris.

Earlier, as the Belle Ãpoque reached its climax in 1900, a younger Picasso was hurriedly sketching the clients and prostitutes dancing at the clubs of Montmartre, just as Toulouse-Lautrec's âJane Avril' was appearing on advertising columns around the city, thanks to the new techniques in colour printing. It was somehow symbolic that the Moulin Rouge, built in 1885 as a windmill, should be converted to a dance hall in 1900, when the famous red sails came to signify not an advancing technology but a different aspect of the new century â hedonism, sexuality and the pursuit of pleasure. These places of entertainment advertised themselves as refuges from the modern and the technological, as places where the primitive and instinctual could find free and uncensored

expression. Paris, which Benjamin called âthe capital of the nineteenth century',

1

was a place of exemplary order and impressive social control. Yet part of that order was the permitted existence of

lieux de plaisir

â âplaces of pleasure' â on the margins of the city, behind the Wall in Montmartre and later in Montparnasse.