Tampered (12 page)

Authors: Ross Pennie

Horvat's arms didn't budge.

Hamish focused more intently on his own upper limbs: fists balled, elbows bent, arms stiff. Stars swirled in the consuming darkness. He heaved for his life.

Horvat's thumbs gave way. Wires flew, the monitor wailed, and Hamish stumbled from the bedside. He collapsed on a chair near the door and gasped. Lungful after lungful.

Three nurses stormed the room and flew into action, forcing Horvat back into bed and reconnecting his tubes and wires.

“Canada Army kill . . . kill . . .” Horvat bellowed. He pointed at Hamish's chest, his eyes as wide as gun barrels. “Goddamn maple-leaf soldiers.” He bared his teeth, apparently incensed by the Canadian flag embroidered on Hamish's lab coat. “Always stinking drunk.”

In the following days, Hamish had kept his distance and let the antibiotics do their thing for his delirious patient. Horvat recovered and was discharged home, though it had seemed strange for a previously healthy man to come down with listeria meningitis, a disease of the elderly and medically fragile. Hamish had chalked it up to one of medicine's inexplicables.

He stared at the empty muffin cup scrunched in his fist, then tugged his tie away from his throat and massaged his neck. A second case of invasive listeria was coming to mind â Gloria's mother, Raimunda, infected a month after Horvat. She, too, had responded well to treatment. But a few weeks later she came down with gastro and died very quickly. Was it really gastro? Or had her listeria relapsed, caused an illness that mimicked gastroenteritis, and finished her off before any tests could be run? Zol had asked the coroner to send off a post-mortem blood culture, but it would be weeks before the provincial laboratory would report the result, and it would go only to the coroner.

The textbooks didn't consider listeria a proper intestinal pathogen. Laboratories looked for listeria in critical samples like blood and spinal fluid, but they never looked for it in stool specimens. Conventional wisdom dictated that detecting listeria in diarrhea stools was of no diagnostic value because the germ was present so often in the feces of healthy people.

Was that piece of conventional wisdom a myth, a medical old wives' tale that could lead to errors in diagnosis?

There was only one way to find out.

Hamish dashed back to the Moun-tain Wing, grabbed the phone in the nursing station, and dialled the microbiology laboratory at Caledonian Medical Centre. He asked for Ellen Ballyk, the chief technologist.

“She's at a meeting,” said the secretary who took the call.

“Until when?”

“I don't really know. A couple of hours, maybe?”

Hamish checked his watch â ten thirty-five. He wasn't waiting any two hours. “I need to speak to her now.”

“Perhaps one of the technologists can help you.”

“No, I only want to speak to Ellen.”

“I'm sorry, sir. But she told us not to disturb her.”

Hamish hated meetings. They were always getting in the way of the real work of looking after patients. “For God's sake, this is important.”

“I'll put you through to one of the techs.”

Before Hamish could protest, the line clicked, and Muzak exploded in his ear. Just when he thought he couldn't stand the screech of overly cheerful violins one more second, the line clicked again and a male voice said, “Can I help you?” By the man's no-nonsense tone, it was clear he'd been warned about the hostile caller on the line.

Hamish paused, rolled his eyes, then took a deep breath. “This is Dr. Hamish Wakefield. I understand that Ellen is in the middle of an important meeting. But I really need to speak with her without delay.”

“Can I help you find a test result?”

“No, I don't need a result. I just need Ellen.”

“The thing is,” said the tech, “she left her phone and pager in her office. The best we can do is send someone to pull her out of the meeting.”

“Now we're getting somewhere.”

“It'll take a while. The conference room is in another building.”

“I'll leave you my number. Have her call me as soon as she can.”

Half an hour later, Ellen called him on his mobile. She sounded anxious and out of breath. “Dr. Wakefield. What's wrong? Is this a code indigo?”

“Indigo? Not that I know of. What's that?”

“Bioterrorism.”

“No. But it is life and death.”

“Jeez. This was a heck of a way to be sprung from a boring meeting. You really frightened me.”

“Sorry.”

“Never mind. How can I help you?”

“Do you still have all the stool samples sent to you this year from Camelot Lodge?”

“Of course. Until an outbreak investigation is wrapped up, we keep every sample frozen and available for further testing.”

“I need you to culture those stools for listeria,” Hamish said.

“You're not serious.”

“Of course I am.”

“But there's no validated stool-culture method for listeria.” Ellen's tone was emphatic. She was never one to break the rules.

“I know, I know. It would go against the international lab standards.”

“And for good reason. Listeria isn't a recognized cause of gastroenteritis.”

She knew the conventional wisdom cold. But sometimes it paid to be unconventional. “That's the party line,” Hamish said. “But maybe there's a listeria clone that's crashing the party. And causing the gastro that's baffling us at Camelot.”

“And you want me to culture all those Camelot stools for listeria?”

“At this point, it's the best idea I can come up with.”

“It would be a big job. And I'd have to get hold of the appropriate culture medium.”

“How soon could you get it?”

“It would depend on my supplier. But I gotta tell you . . .”

“What?”

“It would to be an expensive project. And not just the culture medium. I'd need to pay overtime staff. Have you got a budget for this?”

Hamish thought about it for a moment, then nodded into the phone. “The health unit will pick up the tab.”

“You're sure?”

“Of course.”

“And will you take responsibility for reporting the results? As a technologist, I can't do that. Not with an non-sanctioned method.”

“No problem.”

“Well then, if the health unit covers the overtime, I might even be able to get started today. That is, if my supplier has the special medium in stock.”

Hamish ended the call, sat back in his chair, and stared through the window toward the craggy face of the Escarpment. It was going to be tricky making sense of Ellen's results. No one had ever chased listeria as a credible cause of epidemic gastroenteritis.

And how forgiving would Zol be if this turned out to be an expensive wild-goose chase?

At four o'clock that afternoon, Zol greeted the Camelot Irregulars at the door to the library, down the hall from his office. There was a gentle camaraderie among Art Greenwood, Earl Crabtree, and Phyllis Wedderspoon, but the concentration in their faces underscored the seriousness of their undertaking. They all shared the worry of Betty's precarious condition. And they knew any one of them could be next. Except Phyllis, perhaps, who seemed invincible.

“Nice view you've got here,” Art said, pointing through the picture window. “Not much haze today. You can see the CN Tower.”

From four floors above the brow of Niagara's precipitous escarpment, it

was

an impressive view â Concession Street's bustle at their feet, lower Hamilton's geometrical grid in the middle distance, and Toronto's towers across the lake, hovering like disdainful ghosts.

Art cupped his hands above his eyes and peered at the panorama. “I remember the day they opened the Skyway. Must be fifty years ago. That bridge seemed like a fantasy much more than an engineering marvel. And from here, the way it soars over the lake and Burlington Bay, it's still an awesome sight.”

Natasha helped the visitors out of their winter coats and into chairs around the conference table. The look on her face was a mix of worry and excitement. Zol knew how she loved the hunt of an epidemiological investigation, but cared so personally about the outcome that worry lines were etching themselves deeper and deeper into her forehead.

Art wheeled to an empty place at the table and pulled off his well-worn gloves. “Dr. Wakefield sends his regrets.” His eyes showed the seriousness of the situation. “The cases keep piling up on the Mountain Wing.”

The feather in Phyllis's hat flashed a yellow alert as she dipped her nose into the quilted bag in her lap. She lifted a sheaf of papers from the depths of a patchwork of blue jays and daffodils. “I'll be taking notes, and be certain to keep him abreast of our proceedings.” She exchanged conspiratorial glances with Art and folded her hands on the table.

Earl wiped the sweat from his brow with a handkerchief. Zol didn't like the pallor in the man's face. Either the medication survey had exhausted him or he was anxious about presenting their results. Zol wished the group had accepted his offer to meet at the Lodge. This trip looked like it was more than Earl could handle. And by the way his pelvis wobbled when he walked, his arthritis was acting up. Phyllis had insisted on holding the meeting at the health unit, confessing they needed the fresh air and exercise.

Zol extended his hand to the fourth member of the contingent, a woman he'd never met. “Welcome,” he said, “I'm Zol Szabo.”

“Myrtle Hastings,” she replied. She'd dressed for the occasion in a royal-blue suit she complemented with a string of pearls and matching earrings.

“Myrtle and Maude keyed in the data,” Art explained. “Maude would have joined us but she has another appointment.”

As Myrtle beamed, Zol turned to Earl, who looked desperate for encouragement. “I understand the medication survey was your idea, Earl. Would you like to start?”

Earl wiped his face, then massaged the back of his neck with gnarled fingers. He was clearly flustered. “It's Phyllis who has the gift of the . . .” He seemed to catch himself, then continued in a quieter tone, “She's much more eloquent.” He turned to Phyllis, his broad face pinched. “Please . . . You've got the papers. You start.”

Phyllis looked surprised, but accepted the compliment with a proud smile. “If you insist.”

She explained that when the kitchen at Camelot Lodge did not appear responsible for the ongoing gastro outbreak â more than thirty episodes since early January, she reminded Zol â they turned their attention to their medications.

“After all,” Art said, “collectively we swallow hundreds of pills a day.”

Phyllis eyed Art impatiently. She liked having the floor and didn't appreciate the interruption. “Some of us far more than others,” she clarified. “We created a . . . you know . . . a whatchamacallit,” said Phyllis, looking searchingly at Natasha.

“A database,” Natasha said.

“That's it. Yes, a database. It lists every medicine taken by every resident in the past three months.”

Zol couldn't help asking, “What does Gloria think about you doing this?” Nursing-home operators could be touchy when it came to anything that smelled of scrutiny, and they were expert at hiding behind the residents' confidentiality card.

Art waved his hand dismissively. “No one's seen her since Tuesday. She must be holed up in her apartment, nursing her injuries.”

“We don't need

her

permission anyway,” Phyllis said. “Just the residents'. And they gave it unanimously.”

Zol knew it was unlikely they'd obtained consent to snoop into the records of the Mountain Wing residents incapacitated with dementia, but this was no time to stand on ceremony. As a public health official investigating an outbreak, he was permitted to look at all pertinent facts. If anyone asked, the Camelot Irregulars had been working on his behalf. “How did you enter the data so quickly?” he asked.

“The medication record was very helpful,” Art said.

Phyllis stopped him with her

I'm-speaking

look, then bestowed Myrtle with her smile of approval. “Myrtle and her sister Maude used to be professional keypunch operators. And they haven't lost their touch.”

Myrtle gave a shy bow, then held up her hands and wiggled her fingers. All those years at the keyboard and they showed no sign of arthritis. Was repetitive strain injury only a new-age condition?

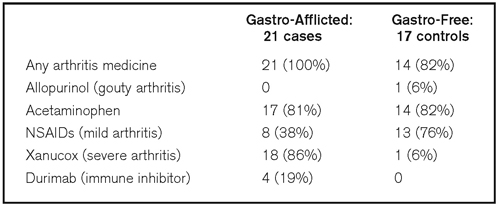

“We divided ourselves into two groups,” Phyllis continued. “Gastro-afflicted and gastro-free. Twenty-one in the afflicted group and seventeen gastro-free.” She nodded toward Natasha. “We could never have analyzed the data without Miss Sharma's guidance. It's one thing to collect the information and type it into the computer, but quite another to make sense of it.”

“Actually,” Natasha said, “the relational database did the analysis. I just nudged it in the right direction.”

“It doesn't pay to be too modest, my dear,” Phyllis said. “You helped us draw some important conclusions.” Her smile held the promise of a revelation as she passed around printed copies of a data table.

These folks were taking dozens of medications, presumably to keep their minds bright, their hearts ticking, their limbs moving, and their metabolisms under control. How much of this polypharmacy was necessary, Zol wondered, and how much was unbridled collaboration between doctors and drug companies? Which was the stronger motivation, profit or patient care?

“A penny for your thoughts, Dr. Szabo?” Phyllis said.

There were too many drugs and numbers to digest on the spot. No obvious pattern. “Well . . . I . . . I think you've done an impressive job entering all that data.”

“Do you see any correlations?”

“Not yet, I'm afraid.”

“Fair enough,” Phyllis pronounced, then glanced at Natasha as though there was some sort of conspiracy between them. She dipped into her bag and pulled out another set of printed sheets. She handed one to Zol. “Now, have a look at this.”

The page held another table, much shorter than the previous.

Zol couldn't take his eyes off the last two lines of the table. “This is an impressive correlation.” He looked at Natasha. “There's no mistake?”

“We went over it three times. Checked the numbers against the medication administration record. And I personally verified that those nineteen people have been taking Xanucox, and no one else.”

“And the Durimab?” Zol said.

“That as well,” Natasha said. She paused and scanned the faces of her four partners. “And there's more. Two of the four getting Durimab injections have died.” She ran a finger down a page in her scribbler. “Nellie Brownlow, the Prime Minister's aunt. And Gloria's mother, Raimunda Ferreira, who recovered from invasive listeria, then got gastroenteritis and passed away last week.”

Zol stabbed the data table with a forefinger. “We'd better keep an eye on those two others getting Durimab.”

“You're . . . you're looking at one of them.” Earl's face, somewhat pale a few minutes ago, was ashen. He wiped his forehead, then balled his hanky in his fist.

A moment later, his eyes glazed and his teeth began to chatter. His knees and elbows hammered against the chair in a violent shiver.

Zol hadn't seen a rigour that severe since he was an intern. He felt Earl's damp forehead. It burned with fever. Natasha handed Zol a glass of water, but when he tried to press it into Earl's fist, it was as though someone had thrown a switch. Earl's shivering ceased, his arms hung limp, the light vanished from his face. He teetered for a second then slumped unconscious against the table.

Natasha grabbed the phone and punched nine-one-one.