Tamam Shud (12 page)

Authors: Kerry Greenwood

Subsequently, the autopsy reports, the suitcase, and

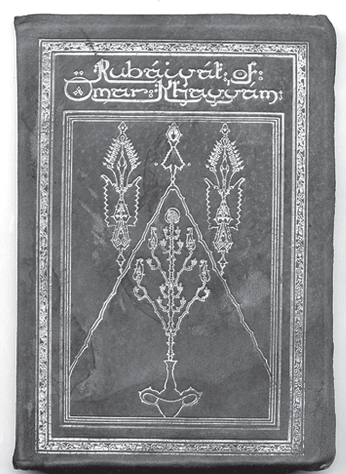

The Rubaiyat

were thrown out in successive police springcleanings. Other writers have waxed indignant about this but I perfectly understand. The police evidence lockers are always bulging with stuff, so when a case is stonecold, that is what has to happen to the evidence. Besides, supposing we still had the actual socks that Somerton Man wore, would it help us at all? Even if we had samples of his DNA, to whom would we compare it? I have to admit I do wish that the actual autopsies had survived but want, as Grandma used to say, must be my master.

Just after the Coroner called it quits, a New Zealand prisoner named EB Collins announced that he knew Somerton Man. The story appeared in the

Sunday Mirror

, which was published in Sydney. Gerald Feltus, who has access to the police reports, states that the New Zealand police interviewed Mr Collins, who declined to impart any more information, stating that he was going to be paid a lot of money for his story by a newspaper. However, no story subsequently appeared.

A copy of

The Rubáiyat of Omar Khayyám

, the works of a Persian poet that seemed to be the key to the seemingly unsolvable death on Somerton Beach on 31 November 1948.

Information volunteered by prisoners is always suspect but it does show that the Somerton Beach mystery still interested the media. The interest has never gone away. The media have had a lovely time with Somerton Man. My researcher collected over a hundred newspaper clippings from the invaluable Trove on the internet, each of them reporting a new solution to the mystery, all of which somehow proved not to be conclusive.

Then there are the coincidences. Fictional detectives are fond of making pronouncements like âThere are no coincidences', and they are right in two senses â firstly, in the sense that no coincidences can happen in an intricate, infinitely complex world system in which butterflies flapping their wings create tornados, and secondly in the sense that no coincidences are allowed in fiction. Fictional investigations have much stricter rules than investigations in real life. In the Golden Age of detective stories, the most important rule was that the murder should never turn out to have been committed by a wandering axe murder whom no one had previously noticed. This is not because there are no wandering axe murderers in the world; sadly, there are. It is because readers of crime fiction rightly demand three things â a crime, a detective and a solution. Crime fiction is a puzzle and the author must play fair and give the reader all the facts they need to solve the mystery. Coincidences happen all the time in real life but if they happen in crime fiction, the reader

feels cheated. Usually, however, an editor will return a coincidence-ridden manuscript and sternly instruct the author to rewrite it, so the reader never gets to see it.

Coincidences happen in court on many occasions. My favourite was the little ratbag who, after spending his youth with a collection of like-minded friends stealing cars and causing trouble, had been sentenced to a youth training facility but had escaped. He ran away to South Australia, got a job and a bank account, got married, had children and took them back ten years later to visit his old mum in Melbourne, counting, quite reasonably, on the fact that he had changed a great deal and that no one was actively looking for him. Then he stepped out on a crossing and was run over by a car and the police officer who picked him up off the road was â you guessed it â the one who had originally put him away. Apparently, the cop said âHi, Jimmy', and Jimmy said âHi, Sarge'. When the case came to court, I argued that the Children's Court sentence was meant to reform and keep him out of trouble, which it appeared to have done, so could we call it quits? And we did.

There have also been some remarkable coincidences in my own writing career, notably the day when my Muse suggested South China Sea pirates for a novel I was already writing. I was at court at the time and rather busy. âNonsense,' I told her. âI am already writing this book. I can't knock off for a month's research.' But she persisted,

so I said, âAll right, Muse, I have to pass Sunshine Library on the way home. If I put my hand on a book about South China Sea pirates in the early twentieth century, I'll do it. If not, not,' which at least stopped her nagging. On the way home I ducked into Sunshine Library and there in the middle of the returns tray, right in front of my eyes and right under my hand, was

The Black Flag: A History of Piracy in the South China Seas in the Early 20th Century

by James Hepburn. I borrowed the book and put the pirates into the plot because ignoring something like that could cause my Muse to get huffy and I would hate to offend her.

Whole philosophical theories have been based on coincidence or synchronicity. Think of Jung. Think of Koestler. The world is not ruled by straight logic or exact causality. Not all of the things that look as if they might be connected are connected. Not all of the things that happen at the same time or in the same way have the same cause. Take, for example, the cases that are often cited as being similar in some sense to the enigmatic death of Somerton Man.

The first is the case of Clive Mangnoson, a two-yearold child, who, in June 1949, was found dead in a sack on the beach at Largs Bay, which is about 20 kilometres down the coast from Somerton Beach. Lying next to the child was his father Keith, suffering from exposure. The two of them had been missing for four days. The child

had died of unknown causes and the man was unable to give an account of what had happened. They were found by a man who said he had been led to them by a dream. Mr Mangnoson's wife said that the family had been terrorised by a man wearing a khaki handkerchief over his face, who, after almost running her down, told her to âkeep away from the police or else'. Mrs Mangnoson subsequently had a perfectly understandable nervous breakdown.

The connection between the Mangnoson case and the case of Somerton Man is that Keith Mangnoson was one of the people who thought he knew Somerton Man's identity. He had gone to the police and told them that Somerton Man was one Carl Thompsen, whom he had met in Renmark in 1939. So was young Clive Mangnoson killed by unknown means in order to force his father to withdraw his identification? In which case, why did the killer or killers leave Keith alive? Wouldn't it have been easier to kill the father and allow the child to live? And why go about it in a way that inevitably attracted attention, in the same way as Somerton Man had attracted attention?

It sounds like a fuck-up to me and I entirely agree with the proposition that if you have a choice between seeing something as a conspiracy or as a fuck-up, you should always go with the fuck-up. But there may be something in the idea. Perhaps the idiots who killed Somerton Man

so clumsily took out poor little Clive Mangnoson, as well, and drove his father mad. We still don't know what killed that poor little child but small children are fragile creatures and they have always been easy to kill.

Before that, another body had been found on Somerton Beach. The South Australian Register reports that on 12 January 1881 an inquest was held on a man who was found dead by a couple looking for some privacy in the sand dunes. Witnesses had seen the man, heavily clothed for the weather, walking along the beach on 6 January âlooking despondent'. Nothing more was known of him until the lovers found him on 10 January, by which time he had decomposed so far as to be unrecognisable. The man had with him a bloody razor and a knife, both of which would be âmost inconvenient for inflicting the wound on the throat'. The Coroner brought in an open verdict, having decided that there was not enough evidence to point to suicide, although he thought it probable. Like Somerton Man, this man was never identified.

The death of Somerton Man has also been linked to a suicide by poisoning. A certain Joseph or George Saul Haim Marshall was found dead in Mosman in Sydney with a copy of

The Rubaiyat

on his chest. He was the brother of a famous barrister called David Saul Marshall, who was Chief Minister of Singapore. The presence of

The Rubaiyat

at both Marshall's and Somerton Man's deaths strikes me as coincidental in the highest

degree. To my mind, Marshall's suicide seems more likely to be an example of the Werther Effect. In the late eighteenth century, hundreds of young men read

The Sorrows of Young Werther

, a long, soggily romantic, Gothic, self-pitying and very boring novel by the poet Goethe, and then killed themselves in the same way that Young Werther did. Similarly,

The Rubaiyat

might have supported or comforted a potential suicide, since Khayyam's conclusion is that this life is all there is, and once over, it is over forever â a philosophical position that might convince the suicide that the pain they were feeling would finally stop.

Commentators on the Tamam Shud case have also noted that Jestyn gave Alf Boxall a copy of

The Rubaiyat

in Clifton Gardens, which is close to Mosman, and that a woman called Gwenneth Dorothy Graham, who testified at the Marshall inquest on 15 August 1945, was found thirteen days later, naked in a bath with her wrists slit but no

Rubiayat

on her chest. Her death may have been the result of a a suicide pact with Marshall but drawing a connection with the death of Somerton Man seems to be stretching coincidence too far. In short, with the possible exception of the Mangnoson case, the other cases most commonly compared to the Tamam Shud murder seem to shed no light on the death of Somerton Man.

What then, you might ask, can modern forensic science tell us about him? The scientists must be able to tell

us something, I hear you insisting. After all, they'd clear it up in fifty-seven minutes on

CSI

. Well, let's see.

In March 2009, Professor Derek Abbott, Director of the Centre for Biomedical Engineering at the University of Adelaide, set up a task force of geeks hoping to solve the mystery. Their website is a joy, even if you know no mathematics, which I don't. But although their enthusiasm is charming, even they have not cracked the Tamam Shud code â and if they haven't done it I believe it cannot be done without further information.

When Professor Abbott researched Somerton Man's Kensitas cigarettes, which had been placed in an Army Club packet, he discovered that the Kensitas were actually the more expensive brand. This seems an odd thing to do. Usually, people transfer cheaper cigarettes into an expensive packet out of swank, on the same principle as decanting cask wine into expensive bottles. (You're not fooling anyone with that, by the way). On the other hand, it is not uncommon for someone to offer a down-on-his-luck mate a handful of cigarettes to fill up their own empty packet. I have done it myself. It isn't as insulting as just handing them the whole packet as though it was a charitable donation. So Professor Abbott's discovery raises the possibility the poison might have been given to Somerton Man in the form of a cigarette. And inhaling the poison might have changed its effects. Maybe an inhaled poison wouldn't cause one to throw up.

Professor Abbott also looked at our man's teeth, such as were left of them, and found that Somerton Man had hyperdontia of the lateral incisors, a genetic disorder that is only apparent in 2 per cent of the population, making it both rare and significant. Although his body is buried, we have photographs and a cast of Somerton Man's upper body, allowing us to establish that he also has unusual ears.

Back when Bertillon was setting up his system of physical measurement, which preceded fingerprinting, it had already been noticed that ear shapes could be classified in the same way as fingerprints â although the classification of ears is not as useful, because there are comparatively few ear prints found at crime scenes. (It does occasionally happen, however. One of my clients left behind most of one ear when he dived through a window to escape pursuit, though that resulted in a jigsaw puzzle game called âmatch the missing body part', rather than an expert examination of prints.) Ear prints can sometimes be found on walls and on windows but they have not been as widely accepted as fingerprints and they have been rejected as evidence in the US courts. However, they are, if not unique, pretty distinctive.

A forensic anthropologist Maciej Henneberg, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Adelaide, has provided an analysis of Somerton Man's ears, establishing that he has an upper hollow, called a cymba, which is

bigger than the lower hollow, the cavum. My sister Janet has ears like this with very short lobes, which made piercing her ears painful. (This does not, by the way, mean I believe that we are related to Somerton Man.) The more usual model is the other way round, an ear with a larger cavum and a smaller cymba.

This combination of hyperdontia and an unusually shaped ear appears in photographs of the son of Jestyn/Teresa Powell. Somerton Man had her phone number in his

Rubaiyat

and his body was found just below her house. Was he the father of Teresa's son as the media has suggested? Allow me to observe that this is just like them. After all, the hyperdontia and the ear shape are general family traits. Why jump straight to the conclusion that Somerton Man was Teresa's lover and the father of her child? Why couldn't he be her brother or uncle or cousin? Nothing brings out the ghouls like death and sex or preferably both. It's a truism of newspapers.