Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe (47 page)

Adélaïde Hoche:

Lazare Hoche’s young wife

Agathe:

Josephine’s scullery maid

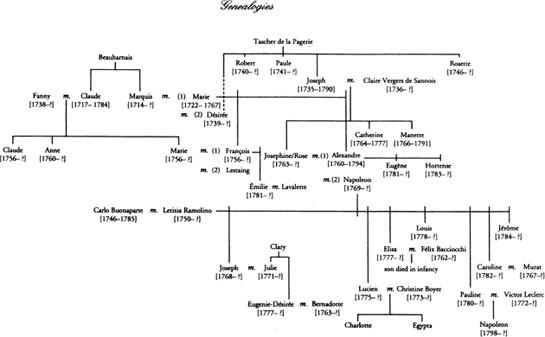

Alexandre Beauharnais:

Josephine’s first husband; guillotined during the Terror

Antoine:

the coachman

Barras, Paul:

a director; Josephine’s friend and mentor

Botot, François:

Barras’s secretary

Bruno:

Barras’s hall porter

Callyot:

Josephine’s cook

Caroline (Maria-Anunziata) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s youngest sister

Charles, Captain Hippolyte (“Wide-Awake”):

Josephine’s intimate friend and business partner

Crény, Madame de:

one of the Glories

Désirée Renaudin:

Josephine’s godmother and aunt; she lives with the Marquis

Elisa (Maria-Anna) Bonaparte:

the oldest of Napoleon’s sisters; married to Félix Bacchiochi

Émilie

Beauharnais:

Josephine’s niece

Eugène Beauharnais:

Josephine’s son

Fauvelet Bourrienne:

Napoleon’s secretary

Fesch:

Bonaparte’s uncle (by marriage)

Fortuné:

Josephine’s first pug dog

Fortunée Hamelin:

one of the Glories

Fouché, Joseph:

Josephine’s friend, talented in undercover work

Gontier:

Josephine’s manservant

Hortense Beauharnais:

Josephine’s daughter

Hugo and Louis Bodin:

Josephine’s business partners

Igor:

Barras’s parrot

Jérôme (Girolamo, Fifi) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s brother, his youngest sibling

Joseph (Giuseppe) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s older brother, married to Julie Clary

Julie Clary:

Joseph’s quiet wife

Junot Andoche:

one of Napoleon’s aides

Lazare (Lazarro) Hoche:

Josephine’s former lover

Lavalette:

one of Bonaparte’s aides-de-camp

Letizia Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s mother

Lisette (Louise) Compoint:

Josephine’s lady’s maid

Louis (Luigi) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s younger brother whom he raised like a son

Lucien (Lucciano) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s fiery younger brother

Marquis de Beauharnais:

the father of Alexandre, Josephine’s first husband, and François, Émilie’s father

Mimi:

Josephine’s childhood maid, a mulatto from Martinique

Minerva (Madame de Châteaurenaud):

one of the Glories

Moustache:

Napoleon’s courier

Napoleon (Napoleone, in Italian) Bonaparte:

Josephine’s husband.

Ouvrard:

a financial genius

Pauline (Maria-Paola, Paganetta) Bonaparte:

Napoleon’s beautiful and spirited younger sister

Pegasus:

Eugène’s horse

Père Hoche:

Lazare Hoche’s father

Pugdog:

Josephine’s second pug dog

Talleyrand, Charles-Maurice:

a former bishop, sometimes Minister of Foreign Affairs, always influential

Tallien, Lambert:

Thérèse’s husband

Thérèse (Tallita, “Amazon”) Tallien:

Josephine’s closest friend, one of the Glories

Toto:

Barras’s minature greyhound

P.S.

Ideas, interviews & features

Author Biography

In the Author’s Own Words

Mud Baths & Dusty Coffins: In Search of Josephine B.

An Interview with Sandra Gulland

Recommended by Sandra Gulland

Web Detective

An Excerpt from

The Last Great Dance on Earth

Sandra Gulland

SANDRA GULLAND

was born in Florida in

1944.

Her father was an airline pilot, so the family moved often, living in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, then Florida again before settling in Berkeley, California.

In the fall of

1970,

Gulland moved to Canada to teach Grade

2

in an Inuit village in northern Labrador, an experience she describes as “amazing.” Later, she worked as a book editor in Toronto, and in

1977

she married Richard Gulland. She gave birth to a daughter and son, and in

1980

the family moved to a log cabin near Killaloe (population

600),

in northern Ontario. Gulland started an editorial and writing service, and became the principal of a parent-run alternative school. All the while, she grew vegetables (or “tried to grow vegetables,” as she puts it), raised chickens and pigs, and developed a lifelong fascination with horses. Meanwhile, and always, she was writing.

Gulland’s consuming interest in Josephine Bonaparte was sparked in

1972

when she read a biography about her. Decades of in-depth research followed, which included investigative trips to France, Italy and Martinique, consultations with period scholars and learning French.

The Many Lives & Secret Sorrows of Josephine B.

was published in

1995.

It was followed in

1998

by

Tales of Passion, Tales of Woe

and

The Last Great Dance on Earth

in

2000.

The Josephine B. Trilogy is now published in thirteen languages. Napoleon said that he “conquered countries but that Josephine conquered hearts,” Gulland says. “It’s astonishing. She continues to do so.”

Gulland added to this hugely successful trilogy in 2008 with

Mistress of the Sun,

a novel based on the life of Louise de la Vallière, extraordinary horsewoman and consort to King Louis XIV.

Gulland and her husband now live half the year in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and half in northern Ontario.

“What was Napoleon and Josephine’s bedroom is now a school lunchroom, a plaque on the wall the only evidence that they were ever there.”

Mud Baths & Dusty Coffins: In Search of Josephine B.

From an article by Sandra Gulland, originally published in

The Globe and Mail,

July 25, 1998.

Over two decades ago, I was rather badly bitten by a curiosity bug:

Josephine B.,

it whispered. As in Bonaparte. As in wife of Napoleon. As in, simply, Josephine.

The symptoms of this affliction are obvious: books overflowing shelves, curios gathering dust, obscure portraits covering the walls of my house.

It was a case both chronic and acute: I gave up my day job as an editor and crossed the line, as they say, to the other side. I became an author. Seeking Josephine has been an adventure on a global scale. Researching the first book took me on missions to Paris and to Martinique, where Josephine was born and raised. For the second, I traced her voyage through northern Italy and into the Vosges Mountains of France.

Among the places I travelled was Mombello, Josephine and Napoleon’s summer residence during the first Italian campaign. Described in other books as palatial, the villa surprised me with its small proportions. What was their bedroom is now a school lunchroom, a plaque on the wall the only evidence that they were ever there. In Milan, their Palazzo Serbelloni was also a far cry from the glittering confection commonly described. Now it is a government office building. In Josephine’s suite, the

rooms were small and dark. No wonder she was unhappy here, I thought. The sumptuous villa Manin di Passariano, northeast of Venice, on the other hand, stunned me with its majesty. It was there that Josephine smoothed tempers as Napoleon negotiated a peace treaty with Austria. But nowhere revealed more to me about Josephine than the tiny spa of Plombières-les-Bains in the mountains southeast of Paris.

I arrived there at night. Immediately after arriving in my room, I opened the doors to the balcony facing out over the village. The ancient grey houses clustered along a mountain valley, “as if they had tumbled into a crevice and were too weary to rise,” as I had Josephine describe it in the novel. She loved Plombières, as had her daughter Hortense and Hortense’s son “Oui-Oui” (also known as Napoleon III).

Doctors had recommended that Josephine “take the waters” at Plombières because she’d been unable to conceive a child with Napoleon. (Today, the waters are believed to cure intestinal problems and rheumatism, although not infertility.) As modest as the village is, it had been visited by almost all the royals and demi-royals of Europe of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Its appeal, and its history, can be traced to the Romans, who had also come for the hot mineral water that surges through the rocks under the village.

The day after my arrival, I presented myself at the deluxe Thermes Napoléon, where I managed to convey that I wished to try a variety of water treatments such as those Josephine herself might have taken in the late 18th century. An amused nurse ticked off a number of items on a card. Then, in blue plastic

pantouffles

and a white terry robe, I shuffled through the vast, wet marble halls to my first treatments:

bain radio-gazeux

(a Jacuzzi gone mad), and

compresse thermale

(a series of steaming towels). For my third treatment, I was encased in a heavy cocoon of warm mud followed by a vigorous massage under a shower.

“Nowhere revealed more to me about Josephine than the tiny spa of Plombières-les-Bains in the mountains southeast of Paris.”

“I’d gone to mass in the church of Josephine’s childhood; this was the church of her death.”

After a few inquiries, I located where Josephine had stayed nearby. The former inn was smaller than I’d expected. I looked up at the windows to her corner room (now a dentist’s office), examined the height of the balcony that had given way under her, the fall nearly leaving her crippled. Immediately after her fall, a sheep was slaughtered and she was wrapped in its skin. Musicians had serenaded her as she healed, likely standing on the very cobblestones I myself was occupying.