Tales From Moominvalley (11 page)

Read Tales From Moominvalley Online

Authors: Tove Jansson

Tags: #General, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Animals, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Family, #Classics, #Moomins (Fictitious Characters), #Children's Stories; Swedish, #Dragons; Unicorns & Mythical, #Fantasy Fiction; Swedish, #Short Stories

each other's backs. 'He has to have something to do. The poor little thing's longing for his pleasure-ground.'

And they sent him twice what he had asked for, and, furthermore, food for a week, and ten yards of red velvet, gold and silver paper in rolls and a barrel organ just in case.

'No,' said the hemulen. 'No music box. Nothing that makes a noise.'

'Of course not,' the kiddies said and kept the barrel organ outside.

The hemulen worked, built and constructed. And while building he began to like the job, rather against his will. High in the trees thousands of mirror glass splinters glittered, swaying with the branches in the winds. In the treetops the hemulen made little benches and soft nests where people could sit and have a drink of juice without being observed, or just sleep. And from the strong branches hung the swings.

The roller coaster railway was difficult. It had to be only a third of its former size, because so many parts

were missing. But the hemulen comforted himself with the thought that no one could be frightened enough to scream in it now. And from the last stretch one was dumped in the brook, which is great fun to most people.

But still the railway was a bit too much for the hemulen to struggle with single-handed. When he had got one side right the other side fell down, and at last he shouted, very crossly:

'Lend me a hand, someone! I can't do ten things at once all alone.'

The kiddies jumped down from the wall and came running.

After this they built it all jointly, and the hemulens sent them such lots of food that the kiddies were able to stay all day in the park.

In the evening they went home, but by sunrise they stood waiting at the gate. One morning they had brought along the alligator on a string.

'Are you sure he'll keep quiet?' the hemulen asked suspiciously.

'Quite sure,' the whomper replied. 'He won't say a word. He's so quiet and friendly now that he's got rid of his other heads.'

One day the fillyjonk's son found the boa constrictor in the porcelain stove. As it behaved nicely it was immediately brought along to grandma's park.

Everybody collected strange things for the hemulen's pleasure-ground, or simply sent him cakes, kettles, window curtains, toffee or whatever. It became a fad to send along presents with the kiddies in the mornings, and the hemulen accepted everything that didn't make a noise.

But he let no one inside the wall, except the kiddies.

The park grew more and more fantastic. In the middle of it the hemulen lived in the merry-go-rqund house. It was gaudy and lopsided, resembling most of all a large toffee paper bag that somebody had crumpled up and thrown away.

Inside it grew the rose-bush with all the red hips.

*

And one beautiful, mild evening all was finished. It was definitely finished, and for one moment the sadness of completion overtook the hemulen.

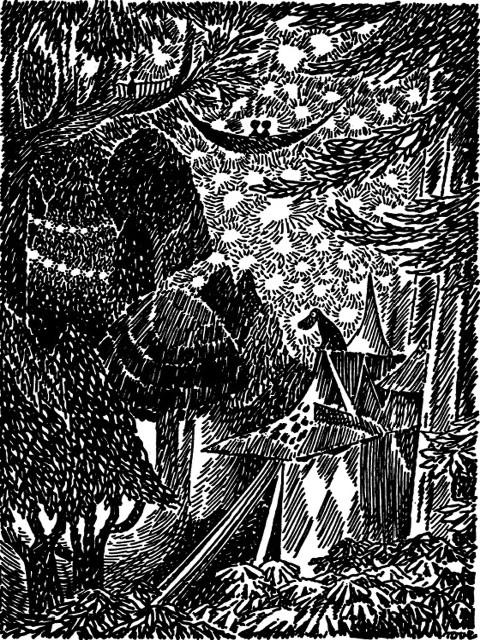

They had lighted the lanterns and stood looking at their work.

Mirror glass, silver and gold gleamed in the great dark trees, everything was ready and waiting - the ponds, the boats, the tunnels, the switchback, the juice stand, the swings, the dart boards, the trees for climbing, the apple boxes...

'Here you are,' the hemulen said. 'Just remember that this is

not

a pleasure-ground, it's the Park of Silence.'

The kiddies silently threw themselves into the enchantment they had helped to build. But the whomper turned and asked:

'And you won't mind that you've no tickets to punch?'

'No,' said the hemulen. 'I'd punch the air in any case.' He went into the merry-go-round and lighted the moon from the Miracle House. Then he stretched himself out in the fillyjonk's hammock and lay looking at the stars through a hole in the ceiling.

Outside all was silent. He could hear nothing except the nearest brook and the night wind.

Suddenly the hemulen felt anxious. He sat up, listening hard. Not a sound.

Perhaps they don't have any fun at all, he thought worriedly. Perhaps they're not

able

to have any fun without shouting their heads off... Perhaps they've gone home?

He took a leap up on Gaffsie's old chest of drawers and thrust his head out of a hole in the wall. No, they hadn't gone home. All the park was rustling and seething with a secret and happy life. He could hear a splash, a giggle, faint thuds and thumps, padding feet everywhere. They

were

enjoying themselves.

Tomorrow, thought the hemulen, tomorrow I'll tell them they may laugh and possibly even hum a little if they feel like it. But not more than that. Absolutely not.

He climbed down and went back to his hammock. Very soon he was asleep and not worrying over anything.

*

Outside the wall, by the locked gate, the hemulen's uncle was standing. He looked through the bars but saw very little.

Doesn't sound as if they had much fun, he thought. But then, everyone has to make what he can out of life. And my poor relative always was a bit queer.

He took the barrel organ home with him because he had always loved music.

The Invisible Child

O

NE

dark and rainy evening the Moomin family sat around the verandah table picking over the day's mushroom harvest. The big table was covered with newspapers, and in the centre of it stood the lighted kerosene lamp. But the corners of the verandah were dark.

'My has been picking pepper spunk again,' Moomin-pappa said. 'Last year she collected flybane.'

'Let's hope she takes to chanterelles next autumn,' said Moominmamma. 'Or at least to something not directly poisonous.'

'Hope for the best and prepare for the worst,' little My observed with a chuckle.

They continued their work in peaceful silence.

Suddenly there were a few light taps on the glass pane in the door, and without waiting for an answer Too-ticky came in and shook the rain off her oilskin jacket. Then

she held the door open and called out in the dark: 'Well, come along!'

'Whom are you bringing?' Moomintroll asked.

'It's Ninny,' Too-ticky said. 'Yes, her name's Ninny.'

She still held the door open, waiting. No one came.

'Oh, well,' Too-ticky said and shrugged her shoulders. 'If she's too shy she'd better stay there for a while.'

'She'll be drenched through,' said Moominmamma.

'Perhaps that won't matter much when one's invisible,' Too-ticky said and sat down by the table. The family stopped working and waited for an explanation.

'You all know, don't you, that if people are frightened very often, they sometimes become invisible,' Too-ticky said and swallowed a small egg mushroom that looked like a little snowball. 'Well. This Ninny was frightened the wrong way by a lady who had taken care of her without really liking her. I've met this lady, and she was horrid. Not the angry sort, you know, which would have been understandable. No, she was the icily ironical kind.'

'What's ironical,' Moomintroll asked.

'Well, imagine that you slip on a rotten mushroom and sit down on the basket of newly picked ones,' Too-ticky said. 'The natural thing for your mother would be to be angry. But no, she isn't. Instead she says, very coldly: "I understand that's your idea of a graceful dance, but I'd thank you not to do it in people's food." Something like that.'