Takeoff! (26 page)

Authors: Randall Garrett

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Science Fiction; American, #Parodies

“Oh, there you are,” the captain said. “I wanted to know if you needed that incubator any more.”

“Just what I was going to talk to you about. I was looking things up in the regulations, and I found we can toss out a lot of stuff-a lot of the cheaper cargo.”

Dumbrowski nodded slowly. “You looked it up, eh? That’s good. But, you know, I hate to throw anything away—and I don’t think I will.”

“But, captain—”

“Will you kindly go back down those stairs? I’m getting tired of just standing here. Let’s go to Devris’ room.”

Drake retreated obediently. They went to the navigator’s compartment, and Dumbrowski knocked resoundingly on the door. “Pete! It’s me.”

“Come on in, skipper,” Devris said.

Dumbrowski looked at the doctor. “I wouldn’t want to open the door while he was cleaning lenses,” he said. “It might get dust on them if I opened the door too suddenly.”

“I See,” said Drake.

They pushed the door open and sat down.

“Now, about this jettisoning cargo,” Dumbrowski began. “I don’t think it’s necessary. Besides, we just couldn’t dump all the stuff we’ll need. We couldn’t get rid of all your duck food, could we?”

“No-o-o; we couldn’t.”

“But we’ll need that space. So, I have an idea. Look; we’re a good long way from the nearest large gravitational body. Is that right, Pete?”

“I haven’t detected anything in the past five weeks. We’re nine light-years from the nearest star. It’s a blue-white; you can’t miss it if you look out the ports.”

Dumbrowski nodded and looked back at Drake. “So here’s what we do: We take all the stuff we can and cart it outside and attach it to the hull with magnaclamps. That includes all those drums of duck food, and everything else. The brooders, too, when you’re through with ‘em.

“Then, if we need anything, all we have to do is go out and get it. Follow?”

Devris just nodded, but Drake felt rather dazed. It had never occurred to him that it was possible to throw something overboard without throwing it away.

I’m just not used to

thinking in terms like that,

he thought. I

keep thinking of aircraft.

Then he thought of something else. “What do we do when the rescue ship comes?”

“Well, they’ll be able to take part of the cargo, and we’ll haul back in the rest. Those ducks can be crowded for a couple of days, can’t they?”

“Sure; two days won’t matter.” After all, he decided, it wouldn’t really crowd them much. By that time, all the feed would be gone—or at least most of it would.

“Good,” said Dumbrowski. “Good. There’s one other problem. Who’s going to clean up after the ducks?”

Drake smiled a sickly smile. “I guess we’ll all have to work at it. It’ll all have to be carted to the disposal.”

“Three cheers.” Dumbrowski stood up. “Well, MacDonald and I will start hauling stuff outside.” And with that, he heaved himself up and walked out.

“You know,” Drake said, looking at the closed door, “that guy worries me. For the past couple of weeks, I thought that... well—” He stood up and looked at his hands, frowning. “I thought we’d arrived at an understanding.” He looked up at Devris. “But he still seems worried about something.”

“Well, sure he is,” Devris said. “He’s not going to be in the best of odor with the Commission.”

“Why not?”

“You mean you don’t know?” Devris sat down again on a nearby chair. “Why, man, he’s in trouble. So am I, and so is MacDonald—although neither of us is in as bad a jam as the skipper is.”

“Why?”

“Because the ship has been disabled. We don’t have any reasonable explanation for it. I’m in a jam because he had the control panels open when the duck walked in. But Dumbrowski is in a jam because he’s captain, and all this is his fault. He’s directly responsible for the whole thing.”

Devris wasn’t looking at Drake now; he was looking at his fingernails. “Maybe you wondered,” he said, “why the skipper was so sore at you after the accident. Maybe I should have told you before this, but here it is.

“The

Constanza

is Dumbrowski’s whole life. Sure, his little wife is a nice gal, but she’s not something you can anchor your life to. Dumbrowski’s pinned his life to Constanza.”

Drake chewed at his lower lip. “I can see that. Sure. But what did I do?”

Devris looked up from his fingernails. “It isn’t something you did. It’s something you can’t be held responsible for.

“The ship has been wrecked. For the first time in his career, Dumbrowski has had to call for help because his ship was out of commission.

His

ship. The Constanza.

“I’m responsible because I brought the duck up. And Mac, as I said, is responsible because he shouldn’t have let the duck get in. But Dumbrowski may never get another promotion-it’s his ship that was wrecked.”

“I see,” Drake said slowly. “And I’m not responsible at all?”

“Not as far as the Commission is concerned. It couldn’t be shifted on to you, even if you wanted it to be.” Devris smiled a little. “And I know you well enough after all these weeks to know that you’d take responsibility if you could. But it won’t wash. It can’t be done. We’ve had it-that’s all.”

Heat. Damp, soggy, broiling heat. Unpleasant, miserable heat, from which there was no escape. And a great burden of weight that sapped the strength rapidly in the hot, wet air.

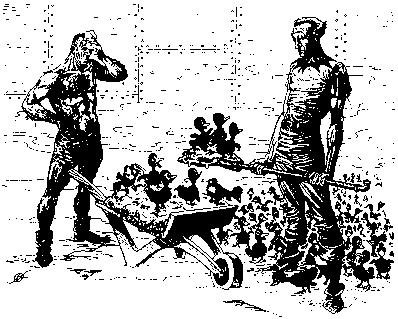

MacDonald lifted another shovelful and dumped it into the wheelbarrow. He was stripped to the waist, clad only in a pair of sport shorts and his boots, and the perspiration ran down his neck and chest and back, soaked into the shorts, ran on down his legs, and collected in soggy pools in his boots. His hands were slippery on the handle of the improvised shovel, making it difficult to work.

Across the room, Drake was surrounded by hundreds of awkward little birds who chorused their monotonous

wakwakwak

.

MacDonald stopped shoveling for a moment and said: “I’m glad I’m not the feed man around here; I’m perfectly happy to handle the other end of the operation.”

“I don’t follow you,” said Drake.

“No, but the ducks follow you,” the engineer pointed out. “It would drive me nuts to have them underfoot all the time.”

Drake put more feed in the pans. “You mean you think they follow me around just because I feed ‘em?”

“Well, don’t they? You give ‘em their goodies; I just clean up after ‘em.”

“It isn’t that,” Drake said. “Even if you fed them, they’d still follow me; I’m the first moving thing they saw after they hatched. It’s a built-in reflex. They think I’m their mother.”

MacDonald plied his shovel again. “In that case, I am gladder than ever. Imagine being mama to thousands of ducks.” He lifted the scoop and dumped it into the wheelbarrow. “Imagine. Thousands and thousands of ducks. Following you. Loving you. ‘Mama! I stubbed my little webby foot, Mama. Kiss it and make it well.’”

“Stop!” Drake said. “You make it sound nauseating.”

“It

smells

nauseating!” boomed a voice from the door. “This whole ship is beginning to smell like a chicken coop!”

“Duck coop,” MacDonald corrected as Captain Dumbrowski came on in.

“Where are you taking that?” Dumbrowski asked, pointing at the wheelbarrow.

“To the disposal. Why?”

“Well, we can stop that right now! You’re an engineer, it says here; you ought to be able to figure it out.”

MacDonald stopped and wiped his forearm over his dripping brow. “You mean clogging the disposal? Nah. There isn’t that much.

“There will be; there will be. Drake! Are these figures you gave me on feeding correct?”

Drake dusted crumbs of feed from his fingers, and walked toward Dumbrowski. “I’m pretty sure they are—why?” As he walked, the ducklings followed lovingly.

“According to this, each one of those ducks will eat approximately seventeen kilos of feed in the next fourteen weeks. At the end of that time, they’ll mass about four kilos each.”

“That’s right.”

MacDonald dropped his shovel. “By the Seven Purple Hells of Palain! Nearly sixty-five thousand kilograms! The disposal won’t take it-not by a long shot!”

Drake said: “Well, I’ll admit there’ll be more per day as the ducks grow, but—” Then he stopped. “What can we do?”

“Do?

There’s only one thing we can do. Dehydrate the stuff and dump it overboard!”

Drake looked down at the ducklings clustered around his feet. “But we can’t do that! We’ve got to reclaim the grit!”

“Grit? What do you mean grit?” Dumbrowski asked.

“Sand and gravel. Ducks don’t have any teeth, so they have to eat a certain amount of grit to grind up the food in their crops. Without it, they’ll die. But there isn’t enough on board. We were going to hatch these birds on Okeefenokee, where there’d be plenty of it, so we didn’t bother to bring any along.”

“Then what the devil have you been doing?”

“Re-using what we have. It isn’t digested, of course, so I’ve been reclaiming it as fast as it’s eliminated, sterilizing it, and giving it back to them.”

Dumbrowski put a hand over his eyes. “Let me think.”

MacDonald and Drake stood there silently while the captain cerebrated. Finally, he took his damp hand away from his eyes and looked at MacDonald. “The A stage will have to be disconnected and used separately. We can dehydrate the stuff and take the sand out, but the organic section—well, that simply can’t be overloaded. It’ll have to go outside.”

“I can do it,” said MacDonald. “But it’ll mean we’ll have to dump it out the air lock at least once a day.”

“You can do it when we go out to get new cans of food. Make it all one operation,” said Drake.

“Yeah,” said Dumbrowski. “You know,” he went on, with a touch of bitterness in his voice, “this isn’t a spaceship—it’s a sea anemone!”

“I see what you mean,” said Drake.

Overhead, two ducks flapped by.

Two men stood in the decompression room of the air lock while the pumps labored to reduce the pressure to zero. Their spacesuits swelled a little as the air left the room, and between them, a box of grayish powder churned softly as the atmospheric gases between the particles of powder worked their way out,

“Are you sure you’ll be all right, Doc?” MacDonald asked.

“I think so. With this nylon rope to anchor me, if I get nauseated again, you can pull me back.”

“Well, it will be easier with two of us, but Devris could have gone instead.”

“He’s got to keep shoveling. I can’t scrape up the stuff from the floors,” he explained.

“Oh? Why not?”

“Because I can’t keep the ducks away from me. Every time I lift up a scoopful, I get three or four ducks with it!”

MacDonald shook his head inside the bubble of his space helmet. “Poor mama duck. Or should I say Papa Drake?”

“You should say nothing of the kind,” the doctor said.

The “all clear” light winked on, and MacDonald opened the outer door.

“You go out first, Doc. Ease yourself past the barrier field slowly. Keep a hand on the edge of the door. And remember, you’re not falling. Just keep your eyes open.”

Drake did as he was told, and, in a few seconds, he was outside the ship and outside the paragravity field.

“How do you feel?” MacDonald’s voice came over the phone.

“All right. A little confused, but I’m not sick. And everything isn’t spinning around.”

“O.K.; I’ll be right with you.” He came out, dragging the heavy box with him. “Now, can you clamp your boots onto the hull? They’ll come on automatically; all you have to do is put them flat on the metal.” He demonstrated, and Drake followed suit.

“I’m O.K., now,” he said. “Here—let me carry the box while you get the food.”

“Fine.” MacDonald raised a gloved finger and pointed. “The dumping ground is right back there near the tail.”

Drake looked around him. Here and there, spread over the outer hull of the ship, were fantastic-looking shapes—various pieces of the cargo which had had to be taken outside. He could see the incubator looming queerly in the dim illumination of the far-off stars.

MacDonald was making his way toward a jungle of steel drums which held the duck food. Drake watched him for a moment, then started walking toward the tail of the ship.

It was an eerie feeling; the ship was big, but it wasn’t big enough to make one feel one was walking on a planet. The horizon was much too close. His boots were a little difficult to handle at first; the magnetic soles stuck tenaciously to the hull and had to be pulled off with each step. Finally, he found it easier to shuffle along, sliding the magnets over the hull.

Ahead of him, he saw a huge white patch on the hull. His helmet light gleamed off its surface. The dumping ground. He shuffled into the area, his boots raising clouds of the stuff, which only settled very slowly under the feeble pull of the ship’s orthogravitational mass.

When he reached a spot near the middle of the heap, he turned the box upside down to dump it.

Nothing happened. The stuff just stayed in the box.

Sure

, he thought to himself, grinning;

not enough pull to make it fallout

of

the

box.