Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures (71 page)

Read Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

He found himself in a narrow, winding street, all dark and forsaken. He had no idea of how he had got there, but seemed vaguely to remember a hand on his elbow, tugging, guiding. The weight of his mail pulled at his sagging shoulders. He could not tell if the sound he heard were the cannon fitfully roaring, or a throbbing in his own head. It seemed there was someone he should look for – someone who meant a great deal to him. But all was vague. Somewhere, sometime, it seemed long, long ago, a sword-stroke had cleft his basinet. When he tried to think he seemed to feel again the impact of that terrible blow, and his brain swam. He tore off the dented head-piece and cast it into the street.

Again the hand was tugging at his arm. A voice urged, “Wine, my lord – drink!”

Dimly he saw a lean, black-mailed figure extending a tankard. With a gasp he caught at it and thrust his muzzle into the stinging liquor, gulping like a man dying of thirst. Then something burst in his brain. The night filled with a million flashing sparks, as if a powder magazine had exploded in his head. After that, darkness and oblivion.

He came slowly to himself, aware of a raging thirst, an aching head, and an intense weariness that seemed to paralyze his limbs. He was bound hand and foot, and gagged. Twisting his head, he saw that he was in a small bare dusty room, from which a winding stone stair led up. He deduced that he was in the lower part of the tower.

Over a guttering candle on a crude table stooped two men. They were both lean and hook-nosed, clad in plain black garments – Asiatics, past doubt. Gottfried listened to their low-toned conversation. He had picked up many languages in his wanderings. He recognized them – Tshoruk and his son Rhupen, Armenian merchants. He remembered that he had seen Tshoruk often in the last week or so, ever since the domed helmets of the Akinji had appeared in Suleyman’s camp. Evidently the merchant had been shadowing him, for some reason. Tshoruk was reading what he had written on a bit of parchment.

“My lord, though I blew up the Karnthner wall in vain, yet I have news to make my lord’s heart glad. My son and I have taken the German, von Kalmbach. As he left the wall, dazed with fighting, we followed, guiding him subtly to the ruined tower whereof you know, and giving him drugged wine, bound him fast. Let my lord send the emir Mikhal Oglu to the wall by the tower, and we will give him into thy hands. We will bind him on the old mangonel and cast him over the wall like a tree trunk.”

The Armenian took up an arrow and began to bind the parchment about the shaft with light silver wire.

“Take this to the roof, and shoot it toward the mantlet, as usual,” he began, when Rhupen exclaimed, “Hark!” and both froze, their eyes glittering like those of trapped vermin – fearful yet vindictive.

Gottfried gnawed at the gag; it slipped. Outside he heard a familiar voice. “Gottfried! Where the devil are you?”

His breath burst from him in a stentorian roar. “Hey, Sonya! Name of the devil! Be careful, girl – ”

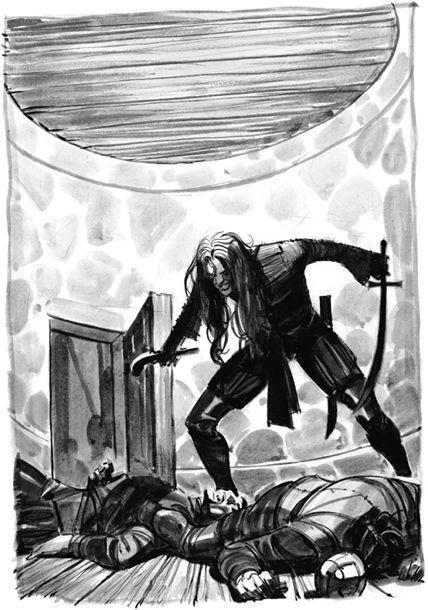

Tshoruk snarled like a wolf and struck him savagely on the head with a scimitar hilt. Almost instantly, it seemed, the door crashed inward. As in a dream Gottfried saw Red Sonya framed in the doorway, pistol in hand. Her face was drawn and haggard; her eyes burned like coals. Her basinet was gone, and her scarlet cloak. Her mail was hacked and red-clotted, her boots slashed, her silken breeches splashed and spotted with blood.

With a croaking cry Tshoruk ran at her, scimitar lifted. Before he could strike, she crashed down the barrel of the empty pistol on his head, felling him like an ox. From the other side Rhupen slashed at her with a curved Turkish dagger. Dropping the pistol, she closed with the young Oriental. Moving like someone in a dream, she bore him irresistibly backward, one hand gripping his wrist, the other his throat. Throttling him slowly, she inexorably crashed his head again and again against the stones of the wall, until his eyes rolled up and set. Then she threw him from her like a sack of loose salt.

“God!” she muttered thickly, reeling an instant in the center of the room, her hands to her head. Then she went to the captive and sinking stiffly to her knees, cut his bonds with fumbling strokes that sliced his flesh as well as the cords.

“How did you find me?” he asked stupidly, clambering stiffly up.

She reeled to the table and sank down in a chair. A flagon of wine stood at her elbow and she seized it avidly and drank. Then she wiped her mouth on her sleeve and surveyed him wearily but with renewed life.

“I saw you leave the wall and followed. I was so drunk from the fighting I scarce knew what I did. I saw those dogs take your arm and lead you into the alleys, and then I lost sight of you. But I found your burganet lying outside in the street, and began shouting for you. What the hell’s the meaning of this?”

She picked up the arrow, and blinked at the parchment fastened to it. Evidently she could read the Turkish characters, but she scanned it half a dozen times before the meaning became apparent to her exhaustion-numbed brain. Then her eyes flickered dangerously to the men on the floor. Tshoruk sat up, dazedly feeling the gash in his scalp; Rhupen lay retching and gurgling on the floor.

“Tie them up, brother,” she ordered, and Gottfried obeyed. The victims eyed the woman much more apprehensively than him.

“This missive is addressed to Ibrahim, the Wezir,” she said abruptly. “Why does he want Gottfried’s head?”

“Because of a wound he gave the Sultan at Mohacz,” muttered Tshoruk uneasily.

“And you, you lower-than-a-dog,” she smiled mirthlessly, “you fired the mine by the Karnthner! You and your spawn are the traitors among us.” She drew and primed a pistol. “When Zrinyi learns of you,” she said, “your end will be neither quick nor sweet. But first, you old swine, I’m going to give myself the pleasure of blowing out your cub’s brains before your eyes – ”

The older Armenian gave a choking cry. “God of my fathers, have mercy! Kill me – torture me – but spare my son!”

At that instant a new sound split the unnatural quiet – a great peal of bells shattered the air.

“What’s this?” roared Gottfried, groping wildly at his empty scabbard.

“The bells of Saint Stephen!” cried Sonya. “They peal for victory!”

She sprang for the sagging stair and he followed her up the perilous way. They came out on a sagging shattered roof, on a firmer part of which stood an ancient stone-casting machine, relic of an earlier age, and evidently recently repaired. The tower overlooked an angle of the wall, at which there were no watchers. A section of the ancient glacis, and a ditch interior to the main moat, coupled with a steep natural pitch of the earth beyond, made the point practically invulnerable. The spies had been able to exchange messages here with little fear of discovery, and it was easy to guess the method used. Down the slope, just within long arrow-shot, stood up a huge mantlet of bullhide stretched on a wooden frame, as if abandoned there by chance. Gottfried knew that message-laden arrows were loosed from the tower roof into this mantlet. But just then he gave little thought to that. His attention was riveted on the Turkish camp. There a leaping glare paled the spreading dawn; above the mad clangor of the bells rose the crackle of flames, mingled with awful screams.

“The Janizaries are burning their prisoners,” said Red Sonya.

“Judgment Day in the morning,” muttered Gottfried, awed at the sight that met his eyes.

From their eyrie the companions could see almost all the plain. Under a cold gray leaden sky, tinged a somber crimson with dawn, it lay strewn with Turkish corpses as far as sight carried. And the hosts of the living were melting away. From Semmering the great pavilion had vanished. The other tents were coming down swiftly. Already the head of the long column was out of sight, moving into the hills through the cold dawn. Snow began falling in light swift flakes.

The Janizaries were glutting their mad disappointment on their helpless captives, hurling men, women and children living into the flames they had kindled under the somber eyes of their master, the monarch men called the Magnificent, the Merciful. All the time the bells of Vienna clanged and thundered as if their bronze throats would burst.

“They shot their bolt last night,” said Red Sonya. “I saw their officers lashing them, and heard them cry out in fear beneath our swords. Flesh and blood could stand no more. Look!” She clutched her companion’s arm. “The Akinji will form the rear-guard.”

Even at that distance they made out a pair of vulture wings moving among the dark masses; the sullen light glimmered on a jeweled helmet. Sonya’s powder-stained hands clenched so that the pink, broken nails bit into the white palms, and she spat out a Cossack curse that burned like vitriol.

“There he goes, the bastard, that made Austria a desert! How easily the souls of the butchered folk ride on his cursed winged shoulders! Anyway, old warhorse, he didn’t get your head.”

“While he lives it’ll ride loose on my shoulders,” rumbled the giant.

Red Sonya’s keen eyes narrowed suddenly. Seizing Gottfried’s arm, she hurried downstairs. They did not see Nikolas Zrinyi and Paul Bakics ride out of the gates with their tattered retainers, risking their lives in sorties to rescue prisoners. Steel clashed along the line of march, and the Akinji retreated slowly, fighting a good rear-guard action, balking the headlong courage of the attackers by their very numbers. Safe in the depths of his horsemen, Mikhal Oglu grinned sardonically. But Suleyman, riding in the main column, did not grin. His face was like a death-mask.

Back in the ruined tower, Red Sonya propped one booted foot on a chair, and cupping her chin in her hand, stared into the fear-dulled eyes of Tshoruk.

“What will you give for your life?”

The Armenian made no reply.

“What will you give for the life of your whelp?”

The Armenian stared as if stung. “Spare my son, princess,” he groaned. “Anything – I will pay – I will do anything.”

She threw a shapely booted leg across the chair and sat down.

“I want you to bear a message to a man.”

“What man?”

“Mikhal Oglu.”

He shuddered and moistened his lips with his tongue.

“Instruct me; I obey,” he whispered.

“Good. We’ll free you and give you a horse. Your son shall remain here as hostage. If you fail us, I’ll give the cub to the Viennese to play with – ”

Again the old Armenian shuddered.

“But if you play squarely, we’ll let you both go free, and my pal and I will forget about this treachery. I want you to ride after Mikhal Oglu and tell him – ”

Through the slush and driving snow, the Turkish column plodded slowly. Horses bent their heads to the blast; up and down the straggling lines camels groaned and complained, and oxen bellowed pitifully. Men stumbled through the mud, leaning beneath the weight of their arms and equipment. Night was falling, but no command had been given to halt. All day the retreating host had been harried by the daring Austrian cuirassiers who darted down upon them like wasps, tearing captives from their very hands.

Grimly rode Suleyman among his Solaks. He wished to put as much distance as possible between himself and the scene of his first defeat, where the rotting bodies of thirty thousand Muhammadans reminded him of his crushed ambitions. Lord of western Asia he was; master of Europe he could never be. Those despised walls had saved the Western world from Moslem dominion, and Suleyman knew it. The rolling thunder of the Ottoman power re-echoed around the world, paling the glories of Persia and Mogul India. But in the West the yellow-haired Aryan barbarian stood unshaken. It was not written that the Turk should rule beyond the Danube.

Suleyman had seen this written in blood and fire, as he stood on Semmering and saw his warriors fall back from the ramparts, despite the flailing lashes of their officers. It had been to save his authority that he gave the order to break camp – it burned his tongue like gall, but already his soldiers were burning their tents and preparing to desert him. Now in darkly brooding silence he rode, not even speaking to Ibrahim.

In his own way Mikhal Oglu shared their savage despondency. It was with a ferocious reluctance that he turned his back on the land he had ruined, as a half-glutted panther might be driven from its prey. He recalled with satisfaction the blackened, corpse-littered wastes – the screams of tortured men – the cries of girls writhing in his iron arms; recalled with much the same sensations the death-shrieks of those same girls in the blood-fouled hands of his killers.

But he was stung with the disappointment of a task undone – for which the Grand Vizier had lashed him with stinging words. He was out of favor with Ibrahim. For a lesser man that might have meant a bowstring. For him it meant that he would have to perform some prodigious feat to reinstate himself. In this mood he was dangerous and reckless as a wounded panther.

Snow fell heavily, adding to the miseries of the retreat. Wounded men fell in the mire and lay still, covered by a growing white mantle. Mikhal Oglu rode among his rearmost ranks, straining his eyes into the darkness. No foe had been sighted for hours. The victorious Austrians had ridden back to their city.