Swine Not? (2 page)

M

R.

B

UFFETT

, I apologize for trying to shove you into the fireplace the day we took photographs at Helen’s house for the book. It was not my fault. I wasn’t being territorial with your space on the sofa. I was just hungry, and you happened to have been sitting on my favorite snack. What can I say? My genetics took over, and I guess I should tell you, though it is after the fact, that you should never get between a pig and her favorite food. That said, I look forward to working with you on future projects. Oh yeah, I am also sorry that I bit you.

Sincerely,

R

UMPY

Don’t Look Down

R

UMPY THE

P

IG

S

PEAKS

I

THINK THERE

comes a time in everyone’s life when the werewolf-like winds of misdirection and the beasts of bad timing put us in an impossible situation. In my case, the question was this: How did a 151-pound pet pig manage to live undetected in a four-star hotel in New York up until this very moment? And what was a pig like me doing, shivering on the ledge of the hotel roof, twenty-five stories above Fifth Avenue?

“Don’t jump,” I heard a voice call out.

“I have no intention of jumping!” I wanted to reply, but I was too scared to move, much less carry on a conversation. The ice beneath my feet gave no quarter. The wind howled and swirled above my head. I prayed that I wouldn’t be turned instantly into an iceboat sail and be sent over the edge — for it was a long, long way down.

“Don’t jump,” the voice repeated.

I had no idea where it was coming from, and I did not dare look down. The skyline of Manhattan was at eye level and bobbing like an apple in a tub. The trees of Central Park bent and swayed in a fierce wind. The noise from the busy avenue below me would block out any attempt I made to squeal for help.

I did not sign up for this kind of trip. Pets rarely do. Our owners just assume we want to go along, and we often find ourselves riding off into the sunset with the excess baggage, iPods, cell phones, and Igloo coolers that belong to our well-intentioned but misinformed masters and mistresses. Pigs are not allowed in four-star hotels in New York City. Somebody should have thought about that before they brought me here.

If only this ice could melt beneath my short, trembling legs. Perched on the ledge, minutes away from turning into a very porky Popsicle, I would have given anything for a local news crew in a helicopter to hover above my chilly head and send some caring soul to rescue me.

A sudden gust of wind slammed into my side, and I did the only thing I could — I stiffened every muscle in my body and resisted the force with all my might. I was as rigid as one of the statues in Central Park across the street. It seemed like an eternity before the wind finally subsided, but I still couldn’t relax a muscle. And then I saw the tiniest bubble of hope arch above the trees. The survival corner of my brain blared out a warning: Don’t look down! Don’t look down!

I sucked in a gulp of fresh air, and for an instant, it was void of the telltale scents of the millions of city animals, plants, and machines I had come to know so well. I ignored the flashing red warning light in my brain, and I let my head tilt ever so slightly down past the ice-covered ledge, down over the trail of taxicabs creeping up Fifth Avenue to the spot where the ball had landed.

“Don’t jump,” the voice called out again.

I was both scared and relieved that someone was watching me, but my eyes were now fixed on that ball as it hit the ground. It was not a falling star, a meteor, or one of a thousand things that could fall out of a New York City sky. No, it was a soccer ball, and it instantly reminded me of where this whole story started, in a much more peaceful place called Pancake Park in a much smaller and quieter town called Vertigo, Tennessee. . . .

Coach Mom

BARLEY THE BOY SPEAKS

“T

HIS IS A SOCCER

game, not a civil war!” our coach shouted to the opposite side of the field as she wiped blood from the nose of a girl lying across her knees. Her words were aimed like missiles at a middle-aged man in a blue jogging suit with moonwalkers stitched across his jacket. Standing on the sidelines with a clipboard on his potbelly, he was smugly nodding his hearty approval that one of our players had been injured.

My twin sister, Maple, ran up with an ice bag, and our coach administered it on the spot. She was a woman who could handle an emergency. I should know — she was also my mom.

Connie, our goalie, was able to stand again in a matter of minutes but was in no shape to continue playing. “Barley McBride!” Coach Mom shouted in that tone I knew so well. “Time to get Rumpy!”

“Vait a minute! Vait a minute!” the Moonwalkers coach barked as our substitute goalie trotted onto the field. “Vhat is dis? Svine?” He led his team in a chorus of laughter, ridiculing our goalie as she waddled toward the net.

“She’s our substitute goalie, that’s what!” Mom replied, thrusting a copy of the roster at the referee beside her.

“Maybe you vant to forfeit now, before da ham sandvich humiliates you.”

“Feel free to get a ball past her, Colonel Klink,” Mom shot back.

The referee studied his folder and then pronounced, “The pig is on the roster! Get her in the goal. Moonwalkers won the toss and will kick first. Five shots per team. Let’s go.”

The Moonwalkers were the undefeated bullies of our soccer league. They were sponsored by the Cadillac dealership in Huntsville, Alabama, where they had their own sports complex. We, the lowly Moccasins from Vertigo, Tennessee, were sponsored by a hippie shoe store and played on a simple field called Pancake Park, the only flat surface in town. It was shaped like a giant footprint, as if some monster stuck his big leg out of a cloud and stomped one of the many hills that surrounded Vertigo.

The Moonwalkers featured an all-American goalie whom our local soccer world called Spiderwoman. Six feet tall, with arms that could reach across the goal, she had gone seven games without allowing a score. But that day her record had been broken — by me. The furious Moonwalkers coach began screaming on the sidelines, and his team responded. They came roaring down the field with a vengeance, sending Moccasin defenders flying. They had taken out Connie, our goalie, in the process of tying the game. Now we were headed for a tiebreaker with the “Goonwalkers,” as we called them.

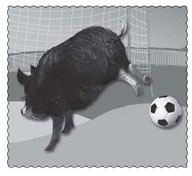

Our pet pig trotted all the way to the end of the field, sporting a custom-made face mask to protect her tender snout. My sister had designed it. Rumpy took her place in front of the net as the opposing team continued to laugh their heads off. Like everyone else, they underestimated her abilities, and it would cost them.

Spiderwoman was back in form and made four dazzling saves, but Rumpy was just as brilliant. She knocked every shot astray of the net. The last striker for the Moonwalkers approached the ball as if he were going to kick it into low earth orbit, but at the last minute, he lobbed a high, arching shot. A collective gasp came from the Moccasin players and fans. They watched in horror, knowing that our goalie (who stood all of two feet, eight inches high) was far beneath the rainbow-shaped path of the final ball.

Agony turned instantly to ecstasy as Rumpy somehow bounded skyward and put her front shoulder between the net and the ball. It bounced harmlessly out-of-bounds.

Seconds later, I put a nasty spin on the final shot and collected my second goal against Spiderwoman. We won the game and were crowned champions of the Alabama / Tennessee Coed Soccer League. Next thing I knew, I was on the shoulders of my teammates, and Mom and Maple were dancing in a circle with Rumpy and the rest of our fans. Manny Brown, the owner of Manny’s Moccasins Shoe Store, accepted the trophy, and we shook hands with the Goonwalkers as they shrugged by us, mumbling, “Good game.”

The coaches were at the end of the line. My mom extended her hand to the opposing coach, but he walked by as if she didn’t exist. I knew Mom, and I knew something was going to happen. You did not insult her or her pig and expect to walk away unscathed.

She waited for the man to put some distance between them. Then she dropped the ball she was carrying. “Hey, Adolf!” she yelled, and as the man turned toward her, she let go with a wicked shot that sailed just above the ground. Steadily it rose until it hit him, as the TV announcers say, “directly in the groin.”

“That’s for the bloody cheap shot at our goalie,” she said as she watched the man rolling on the ground in pain.

“Vait until next year,” the man gasped. “I’ll get you for zis.”

“I doubt that you’ll have the chance,” Mom said.

That night, after the party in the pizza parlor, I asked Coach Mom what she meant by her last words to the Moonwalkers coach.

“Oh, nothing,” she replied casually. “Just another one of my wild ideas.”

In that synchronistic blink only twins know, Maple and I were instantly on the same wavelength, thinking collectively that when Mom said “nothing,” she really meant “something” — and we smiled.

Learning to Play the Angles

BARLEY

I

REALLY HATE

voice mail. That’s what I get when I call my dad to tell him about a game. He calls back, of course, and he always promises that one day he is going to take me to see my favorite player, Darryl Meacham, who plays for Real Madrid in Spain. But by the time he calls, it is past both my bedtime and the initial moment of glory that I wanted to share with him. Dad is usually several time zones away from Tennessee.

As usual, I left him a detailed message about the game and the goals. I also told him about Mom’s little postgame stunt. I knew it would make him laugh.

I used to get real mad about Dad leaving, but that is how I became such a good soccer player. At first, I took my anger out on the ball. I would kick and kick and kick until I thought my leg would fall off. Then I started getting good and began kicking with both feet, and then I started to figure out the angles and how to make the ball go where I wanted it to go. It all helped me deal with the feelings I had about my dad.

Another good thing I learned is that soccer is not a one-man sport. It is a team sport, and you have to depend on, and get help from, strangers. After you help them or they help you, they become your friends. Along the way, you also figure out the angles to the goal, which aren’t that far from the angles of life — even in a town named Vertigo.

The New York Red Bulls are my favorite team, and I hope to play for them when I’m old enough. I was born in New York, although I don’t remember much about living there. I was only three when I left. So how did a future striker for the New York Red Bulls end up in Tennessee? To quote the title of a country song by Tammy Wynette, it was “D-I-V-O-R-C-E.” Back in the ancient days of the 1970s, when the song was popular, a family with just a mother and kids was called a “broken home.” Today it is referred to as a “single-parent family.” Either way you slice it, it is still only half a loaf.

My dad, Oliver McBride, was an English teacher from Boston. He moved to New York, where he met my mom, Ellie Dean. She was a former beauty queen from Clarksdale, Mississippi, who was in culinary school. Though my dad was a fine teacher, he had this pipe dream to be in the movie business. One summer, he got a job as a script consultant on a gangster movie that was filming in Greenwich Village. That was it for the academic world. He quit teaching and started hanging out with other would-be actors and directors, drinking lots of coffee and talking about what they would all do when they got famous.

He and my mom dated for about a year while he wrote his first movie script. They were part of a wild crowd back then. After a party, they ran off to Haiti and got married, and it was only upon their return to New York that my dad learned that not only did my mother come with a steamer trunk full of handed-down Southern family recipes and a closetful of debutante gowns, but she also carried the barnyard gene. This manifested itself in her immediate acquisition of a mean dog, a dozen chickens, a cat, and a baby potbellied pig, whom she scooped up one Thanksgiving back in Mississippi. She somehow managed to stuff all of them into a rental apartment in Greenwich Village. My dad thought he was marrying a Southern belle–turned–city girl, but what he really wound up with was a circus act.

After we were born, we were celebrated at many a party. The champagne flowed, and once our parents actually left us in the restaurant under a table. We were quiet babies; the adults made most of the noise. Space was the first problem, and then the issue was money. The mean dog went to the police-dog program, the chickens went to live on a farm on Long Island, and my dad made his first — and last — sale of a movie script.

The movie business doesn’t appear to have a lot of financial security. That didn’t seem to matter to Dad. He went from being a writer to a producer, but not much was produced. Meanwhile, Rumpy and the cat stayed, and they seemed to get more of my mother’s attention than my dad did. That is when he took off for Hollywood, promising to become rich and famous. Then he planned to return to New York and lather us with luxury.

That didn’t happen. Even at three years old, my sister and I could pick up on it with that “twin thing.” My earliest recollection that our lives were changing was when my sister and I had to start sharing our desserts with our pig. I love my pig, but food is a big deal to a three-year-old, especially dessert.

Somehow my mom managed for a year, baking pies and pastries at a fancy diner, but living in New York ain’t cheap when you’re a petting zoo. One day, a registered letter arrived at her door telling her that her old aunt Margaret had just died and willed her a farmhouse in Tennessee. A week later, she found a job at the famous Opryland Hotel, and we went south, where we have been ever since.

My dad actually did kind of make it in Hollywood — not as a filmmaker but as a copywriter for commercials. Plagued by Catholic guilt, he tried to make up for his lack of availability by helping to fix up the farm in Tennessee.

Dad is presently in Alaska doing a dog-food commercial and working on his sixty-seventh screenplay. All but his first have been rejected. Still, he keeps trying. I guess that once the movie-business bug bites you, you live with the sting. I love my dad, but his accidental fall through the looking glass of Hollywood has warped him. Dad loves us, and he gets along with Mom as long as we all fit into his pattern. I think he sees us, and all other humans for that matter, as bit players in his imaginary films. It never occurs to him that other people might see him as a stand-in in their own movies.