Swim Until You Can't See Land (24 page)

She’s one of your teammates, isn’t she?

Yeah, I know she’ll be really pleased with that. We’ve all been working really hard.

And it’s paying off. After your great swim at the start of the week and now this, you must be doing something right in Bath.

Yeah, we’ve got a great set-up there.

Jase

.

It’s fucking Jason.

He’s doing so well for himself, they apparently now have him in the studio giving his expert opinion to the world.

Without being disrespectful to the rest of the girls, that European title is hers to lose. And she’s not far off Hannah Wright’s British record

.

She’s flying at the moment. She’s worked really hard in training so she deserves it. I know she’s had that record in her sights, and it’s no easy record to beat. Hannah set a high standard

.

My gut tightens as he says my name.

Indeed, I’m sure if Hannah’s watching this she’ll be pleased to see her old teammate…

Shit, I can’t take this.

I hit the power button. The

TV

flashes off. I slam the remote control down on the coffee table; the back pings loose and the batteries spill out, rolling across the table and onto the floor.

I’m shaking, shaking, shaking all over and I pound the sofa cushion. Punch it, punch it, punch it. I don’t know what’s worse. Being completely forgotten about or being talked about like that.

As if they know what it’s like.

They have no right to talk about me like they know how I feel. Like I had my shot, gave up on my own terms.

(as if I’m happy)

I had it in me to set a better record, a faster one. One that Claire Richards couldn’t come close to. She’s stolen my place in history.

I’m out of breath, panting, my chest heaving, in and out, in and out, in and out. My heart hammers and I can’t stop the tears. I think I’m going to be sick.

I slide off the sofa, lie on the floor in front of it. Push my face into the carpet, feel it prickle against my face.

I feel so awful, so fucking awful. Why does it hurt so much? And I have nobody, nobody. I hurt too much to get in touch with my swimming friends, too ashamed to get back in touch with my school friends.

I’m all on my own.

So what happened? I read in the paper that you got injured.

It’s my shoulder.

What happened to it?

What do you mean?

Did you fall or hit it or something?

No, it just happened.

Those Union Jack nails flicker in front of my eyes. My own nails are chipped and peeling. I push my hands away from me, under the sofa, into the dust and crumbs.

I need to paint my nails.

Marièle must have nail polish somewhere.

I get up off the floor, try the door directly opposite the living room.

A cupboard.

Coats and jackets hang from a rail, shoes and boots on the floor beneath. It smells of lavender, smoky and floral. I shut the cupboard, try the next door.

It swings open onto her bedroom. I stop in the hallway.

Should I go in?

I have to. I have to wipe off this chipped layer of polish and start again with a fresh coat. I step into her bedroom, the door shuts behind me. The lavender smell is stronger in here, sickly, cloying, like those parma violet sweets.

The bed’s made, shoes lined up underneath, clothes folded on a chair in the corner, make up and bottles of perfume neat on the dressing table. Chanel No

5

.

I spray it onto my wrist, my neck. The scent hangs, misty, and I breathe it in. The bottle clinks against the varnished surface of the dressing table when I put it down. I rummage through tubs and tubes and aerosols, find a bottle of clear nail polish and a bottle of red. There’s no remover though, so I sit on her bed, use my teeth to scrape off the dried polish stuck to my nails.

The red polish is sticky, can’t have been used for a while, so I apply a layer of the clear stuff over the top. It slicks over the red. The brush of the clear liquid turns pink, contaminates the rest of the polish. I lay my hands out flat on my thighs, wait for it to dry. Flakes of polish lie across Marièle’s cream duvet cover.

There’s a pile of books at my feet.

Angela’s Ashes

The Cinder Path

Women Agents of

WW

2

Great Expectations

A shelf above her bed. An ornament of a blackbird, the porcelain shining, another of a Chinese fisherman. He’s holding a fishing rod, made from a toothpick and a piece of thread, a glass fish tied to the end of it. I push at the fish with my pinkie, it swings from side to side.

I blow on my nails, dab at them with a fingertip. They’ve not dried completely and my finger imprints the sticky polish.

Two photographs stand in frames next to the fisherman, a layer of dust static across the glass.

Old photos, no colour in them, yellow rather than black and white. One’s of a man in uniform. The other is of two girls walking along the street.

Is one of them Marièle?

It’s hard to compare the girls in the photo with that old woman lying in the hospital bed.

So young, but before you know it you’re living alone with just a fish for company.

(I don’t even have a fish)

16

SABINE HAD NEVER

cycled so far in her life. The suitcase containing her Mark

III

radio was slung in a basket on the back of her bike, the brown leather creased and worn. She was glad she didn’t have to carry it, the weight of it already made her bicycle unsteady.

The bicycle is the easiest way to get around once you are in France. It is a common way for women to travel and means that you can take back roads and avoid public transport, including any road blocks or document spot checks.

Sweat ran down her back and forehead, grit from the dusty road stuck to her damp skin. She was grateful for the breeze that blew up her skirt and cooled her legs.

No matter how much Madame Poirier tried to feed her up, she simply did not have enough food to combat the endless hours of cycling. Sabine could feel her clothes, specially measured for her back in London, loose around her waist and bust, her thighs firm.

It took Sabine a moment to remember where she was. Light shone in through the slits of the wooden shutters. Even though she was on dry land now, she could still feel the rocking motion of the felucca.

up and up and up and up and

down down down down

She could smell coffee and sausages cooking somewhere in the house. As her ears tuned in and she began to wake up properly, she realised that she could hear voices through the wall.

Sabine slipped her arms out from the sleeping bag Madame Poirier had made for her. The parachute material was soft and slippery against her skin. She ran a finger along the fine black stitching which held it together. It had been dark when she’d arrived last night. Madame Poirier sat up waiting for her, had sent Alex away, even though he wanted to brief Sabine on Sand Dune. Madame had fed Sabine, bread and cheese, before packing her off to bed. It all felt like a dream now, she’d sleepwalked through most of it.

All these drops we get, I tell the boys bring me the parachutes, I can use them. They groan and moan, we must bury them, Madame, we must. It’s such a waste. They think they can fool me, but I’m not stupid, I know.

Sabine could hear Madame Poirier now. It sounded like Alex was with her.

‘Look at the time, it’s after nine. I need Sabine. She is not here to sleep, she is not here for

un jour férié

.’

‘Sssshhh, I will not have you waking that poor girl. She’s no use to you exhausted. Let her get some rest before you send her off on one of your missions.

Laisse-la tranquille

.’

‘This is important.’

‘Everything is important to you. What use is she if she drops dead of exhaustion halfway down the road? Have some coffee, sit down and speak to me.’

Sabine stopped next to a roadside shrine, set up inside an alcove in the wall. A statue of the Virgin Mary, blue paint peeling from her shroud, too long exposed to the elements. There were dead flowers in pots lying next to the statue, stubs of candles standing rigid in pools of wax.

She untied the silk scarf around her neck, careful not to tug on the silver chain underneath. The cross bounced against her chest as she cycled.

She wiped her face with the scarf then spread it out on the saddle of her bike. A map had been printed on the silk. She glanced at it quickly, before tying it back around her neck and setting off on her bike again.

Sabine closed her eyes, could feel the sleep dragging her down. She sat up. She had to get out of bed, if she let herself drift off she would sleep the whole morning away. Alex already thought she was lazy and weak, she had to prove to him she was an asset.

She knew the attitude of some of the men towards women agents.

She climbed out of the sleeping bag, her legs wobbly and unsteady. The pack containing her clothes lay on the floor next to the bed. Madame Poirier had stripped her of what she’d been wearing the night before.

I think we might be better off burning these rather than trying to wash them.

Sabine pulled a skirt and pullover from the pack and put them on, washed her face using the hand basin in the corner of the room. As she dried her face she looked up into the mirror on the wall.

God, she looked a fright.

She splashed more cold water onto her face, tried to shock some life, some colour into her skin.

I have been ill. Rheumatic fever.

Oh well, she looked the part if nothing else.

Sabine propped her bicycle against a railing. She took one of the tables outside the Café Rouge. There was a poster on the wall behind her.

POPULATIONS ABANDONNÉES,

FAITES CONFIANCE AU SOLDAT ALLEMAND!

It had a picture of a German soldier surrounded by children, the children were smiling and eating bread.

Someone had scrawled ‘

Vive la France

’ over the soldier’s face.

A man went past on a donkey and cart, he nodded at Sabine and she smiled back. A group of German soldiers were seated at a table on the opposite side of the square. Sabine looked up at the clock on the church tower.

Never wait more than five minutes for a rendezvous.

A bell jingled and Sabine turned to see the door of the café open and the waitress step out. She carried a notepad, wore a blue spotted apron tied around her waist.

Alex had said that she was nineteen, but she didn’t look much older than fifteen. She was very pretty, like a young Greer Garson, slim with blonde hair.

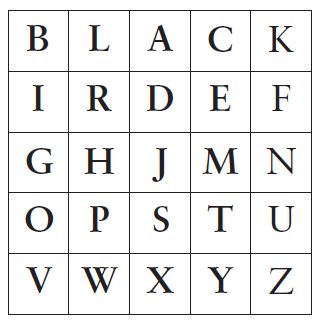

PM FC DO OA PF MU BJ BD JU PM FD BT AR UA FG

The soldiers spotted her and one of them wolf-whistled. The girl blushed, ignored the jeers coming from the other side of the square.

‘

Oui

,’ she said to Sabine.

‘

Je voudrais un café et une pâtisserie, s’il vous plaît

.’

The girl began to write, then hesitated, looked up.

‘How do you take your coffee?’

‘

Noir et très chaud

.’

A flicker passed over the girl’s face. She nodded and disappeared back into the café.

Sabine’s stomach churned, she needed the bathroom. The soldier’s voices carried across the square.

Je m’appelle Sabine Valois.

Je m’appelle Sabine Valois.

One of them said something and the others all laughed. Her dowdy disguise must work. They weren’t interested in a sickly French girl. Not with Natalie around.

Natalie reappeared with a cup of coffee and a crescent shaped pastry. She leant forward to put the tray on the table. As she did so, she bent in close to Sabine. Sabine felt a shiver run up her spine as Natalie whispered in her ear.