Sunlight on My Shadow

Read Sunlight on My Shadow Online

Authors: Judy Liautaud

Tags: #FAMILY &, #RELATIONSHIPS/Family Relationships

Table of Contents

- SUNLIGHT ON MY SHADOW

- COPYRIGHT

- DEDICATION

- CHAPTER 1 THE CABBAGE PATCH DOLL

- CHAPTER 2 MY DAD, JOHN N.

- CHAPTER 3 MY MOM, ETHEL MAY

- PART I - COMING OF AGE

- CHAPTER 4 THE GOODNESS METER

- CHAPTER 5 HUMMINGBIRD NESTS

- CHAPTER 6 EIGHTH-GRADE SEX EDUCATION

- CHAPTER 7 THE ROLLING STONE NIGHTCLUB

- CHAPTER 8 ROUNDING THE BASES

- CHAPTER 9 THREE STRIKES AND I’M BUSTED

- CHAPTER 10 THE INTERVIEW

- CHAPTER 11 CROSSING THE CAVERN

- CHAPTER 12 THE NIGHT MY LIFE CHANGED FOREVER

- CHAPTER 13 BATHROOM JUNKIE

- CHAPTER 14 MICK, GUESS WHAT?

- CHAPTER 15 CONSEQUENCES OF A SWOLLEN BELLY

- CHAPTER 16 FRONT SEAT OR ELSE

- CHAPTER 17 MY SORRY LIFE

- CHAPTER 18 BREAKING THE SILENCE

- CHAPTER 19 HYSTERICAL PREGNANCY

- CHAPTER 20 COMING CLEAN TO MOM AND DAD

- CHAPTER 21 A VISIT TO DR. KELLER

- CHAPTER 22 GOOD-BYE, MICK

- PART II - GROWING UP BEFORE MY TIME

- CHAPTER 23 LEAVING HOME

- CHAPTER 24 HELEN’S WELCOME-WAUPACA, WI.

- CHAPTER 25 MOTHBALLS

- CHAPTER 26 SELF-IMPOSED BOOT CAMP

- CHAPTER 27 BRING ON THE SUNSETS

- CHAPTER 28 LEAVING WAUPACA

- CHAPTER 29 THE HOME FOR UNWED MOTHERS

- CHAPTER 30 THEY CALLED ME JUDY L.

- CHAPTER 31 VISITS WITH MY SOCIAL WORKER

- CHAPTER 32 WAKE-UP CALL AT WAKING OWL BOOKS

- CHAPTER 33 MY BODY GREETS D-DAY

- CHAPTER 34 THE BIRTH

- CHAPTER 35 RECOVERY

- CHAPTER 36 THE BABY IS TAKEN

- CHAPTER 37 HOME TO GLENVIEW

- CHAPTER 38 THE ROTTEN AROMA OF A LIE

- CHAPTER 39 MICK AGAIN

- PART III - COMING TO TERMS WITH MY PAST

- CHAPTER 40 ROCKY MOUNTAIN HIGH

- CHAPTER 41 A STROKE OF GRACE

- CHAPTER 42 SEARCHING FOR BABY HELEN

- CHAPTER 43 THE NEXT STEP

- CHAPTER 44 LOSS

- CHAPTER 45 THE JOY LUCK CLUB

- CHAPTER 46 BLAST FROM THE PAST

- CHAPTER 47 INTUITION

- CHAPTER 48 A CALL TO KAREN

- CHAPTER 49 LOST AND FOUND

- CHAPTER 50 CHANGES

- CHAPTER 51 SUNLIGHT IN THE SHADOWS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ON MY

SHADOW

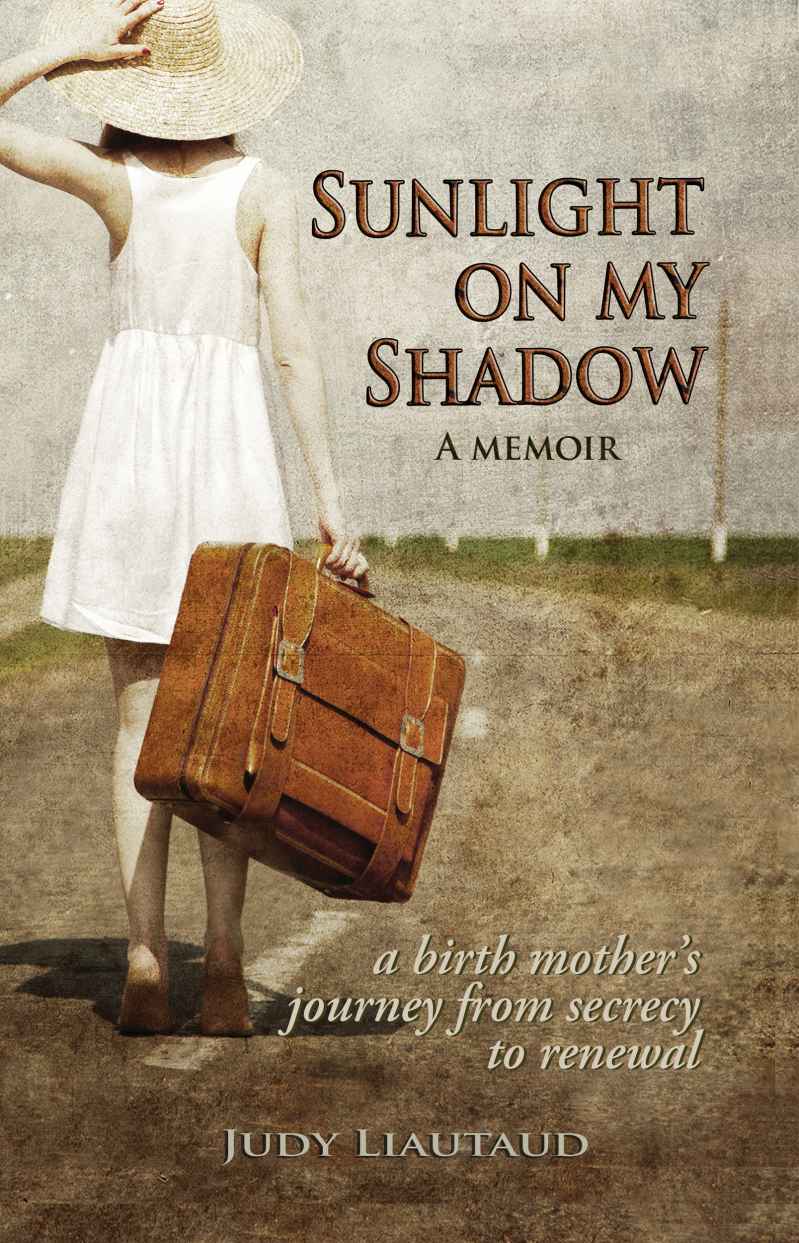

A Memoir

A Birth Mother’s Journey from Secrecy to Renewal

Judy Liautaud

City Creek Press, Inc. ~ Minneapolis

This is a work of non-fiction. In all cases I have tried to be truthful and when necessary I have verified my recollections with others. Most names have been changed, except for the first names of close friends and family.

S

UNLIGHT ON

M

Y

S

HADOW

C

OPYRIGHT

© 2013

BY

J

UDY

L

IAUTAUD

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or in the case of reviews. Address for information: City Creek Press, Inc.~PO Box 8415~Minneapolis, MN 55408

F

IRST EDITION PRINTED

2013

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012916300

Print ISBN: 9781883841171

EBook ISBN: 9781883841072

Published by

:

City Creek Press

PO Box 8415

Minneapolis, MN 55408

This book is for those of us who have been tethered to shame, regret, and secrecy — that we shall soar on the wings of loving acceptance, whole again, and free into the open sky.

HAPTER

1

T

HE

C

ABBAGE

P

ATCH

D

OLL

The last time I played with a doll was over twenty years ago. I thought I was done with all that.

On a spring day in 1984 my two little girls, Kiona and Tessie, were at school. We were living in Cedar Fort, Utah, nestled on the edge of the Oquirrh Mountains, population 341. I was busy sewing hang-gliding harnesses for our flight school, Wasatch Wings, but couldn’t find the scissors. Perhaps my kids were the culprits, so I went down to my girls’ bedroom to take a look. There was the scissors lying on the floor next to one of their Cabbage Patch dolls. Alongside the doll were her adoption papers. You could fill these out, send them in, and get an official-looking birth certificate with your kid’s name on it as the parent. The girls had made a little rag dress for the doll, using my scissors and sewing scraps. The doll looked like an orphan in need of some kind of comfort, so I picked it up. I didn’t pick her up with the usual intention of cleaning a messy floor, but to cuddle her as if I were a child playing house. Nestling her head in the crook of my arm, I cradled her body close to me. I embarrassed myself, acting so childishly, and questioned my sanity. I was thirty-four years old, after all, and had two children of my own. Something urgent nudged me past my ill ease. I sat down on the edge of the twin bed and swayed back and forth while hugging the doll-baby. When I looked into her face, I saw sweet eyes and dark swirls of hair pasted to her head, reminding me of my baby, born seventeen years ago.

I wished I had held her back then. Her body close to mine felt delicious. I hugged tighter. Love pulsed through me with a soft electric hum. I started to cry and squeezed her body closer. I looked into her eyes and told her I was sorry. I was sorry I gave her away and I was sorry I punched my stomach when she was inside me. I was sorry I was missing her life and I was sorry I never held her. I sat there and rocked her while tears dripped down and slid their salty taste into my mouth.

I can’t say how long I was there, sitting on the edge of the bed with the doll in my arms, but I stayed until I had said everything that had been knotted inside of me for the past seventeen years. When my words and tears dried up, I tucked the doll into the twin bed and pulled the covers to her chin. Grabbing the scissors from the floor, I went back upstairs and sat still at the sewing machine. I stared out the window and watched the newly budded leaves swaying on the trees. I felt crusty and smelly, as if I had been camping for a long time, and just took a warm, cleansing shower. I found it strange how emotionally strong I felt, as though my body had been infused with a life force and a renewed capacity for joy, after doing something so insane.

It was then that I realized how much I had been holding inside and how much I was hurting, deep within the dark spaces of shame and regret. A bit of sunlight crept into my darkened heart.

The breakdown in the bedroom didn’t come as a shock. I knew I was hurting. The ache was tangible, a shadowy lump in the left side of my body, inside my ribs. I had forgotten about the movie I had seen a year ago, which likely prompted my impulse to bond with the doll. I was with several midwives, labor coaches, and birth class instructors. It was about helping patients handle the grief of losing a baby in a more tender and caring way. The conventional method, whisking the stillborn away so the woman wasn’t traumatized by a gray, lifeless child, turned out to be more harmful than helpful, the film said. The sweet women had felt their babies alive and well and had whispered to their little ones that they couldn’t wait to welcome them into this world. Then, all of a sudden, there was nothing. No baby. Just silence after the birth. The women yearned to rub their hands over their baby, look at the tiny ears and toes. Well-meaning relatives and friends told the women it was pointless to have a funeral since the baby had never lived. Minimizing the loss made the women feel very alone in their sorrow. After months and years had passed, they wondered if something might be wrong with them because they couldn’t get past their grief. They referred to themselves as emotional wrecks.

To help these women, health professionals were given tools to facilitate the process of grief. They gave the women dolls, proxy children, similar in weight to a newborn. They encouraged the women to role-play the rebirth of their babies, caress the dolls, and tell them how they were missed. Although they were initially fearful that they would crumble under the pain of loss, the women trusted the nurses and let their feelings and words flow. It was a heart-wrenching scene. In the end, the women said this exercise was extremely helpful. Almost all of them reported feeling at peace and lighter.

As I sat and watched the movie, a chord of familiarity resonated in my body. I thought the exercise might do me some good. I thought back to 1967, the last time I saw my baby. A junior in high school, I was one of those girls who got in trouble. I didn’t think I fit the profile of these fallen girls. I came from a good, middle-class, Catholic family. I did my homework and got good grades. I used to grab my white leather missal and walk in the early morning darkness so I could ride the city bus to church. I attended Mass during Lent every day before school started. God had been good to me, answered my prayers. Somewhere along the line, I took a wrong turn. God wasn’t going to get me out of this one, as I prayed rosary after rosary that my period would start.

In the 1950s and 60s, over one and a half million girls got pregnant out of wedlock, were sent away, and gave their babies up for adoption. We were liberating ourselves from the strict moral codes that our parents purportedly lived by, yet there was no readily available birth control, and nobody talked about it. Condoms were guarded behind the pharmacist’s counter and remained there, unless you were 18 and could show an ID to make a purchase. It was before Roe v. Wade. The only abortions I heard of were from a movie I saw at school where desperate teens went for coat-hanger abortions performed by sleazy people who lived off alleyways; the girls escaped death by a thread.

The mothers and fathers of the girls who got in trouble concocted stories to explain their daughters’ absences. School policy did not condone advertisement of this abhorrent behavior, so it was grounds for being expelled. Shunned by society, we were sent far from home to protect our secret. Many of us went away to Homes for Unwed Mothers. Some of these buildings were originally constructed to hospitalize the returning World War II veterans. Then, in the late 1940s, the hospital floors were converted into delivery rooms and maternity wards. Cots lined the walls for sleeping quarters and industrial-sized kitchens adjoined the dining hall. The home I stayed at was stark, yet efficient.

Fictitious names added dimension to our secret fantasy, as we were instructed to never, under any circumstances, give away our last names. We must, however, give away our babies. Our interlude with passion faded like a morning mist as we moped around the building, donning sack like blouses that camouflaged our protruding bellies. We were girls in waiting: waiting for our sentence to be carried out until the days of reckoning. Labor, birth, adoption. Clean and slick. Back home to resume life as usual, miraculously recovered from our alleged illness, instructed to never look back.

The master plan was to keep it a secret and all in my past. When it was over, I’d erase the memories like a swift punch of the delete key. When I was just sixteen, the carefully woven lie was a lifesaver. It would protect me from extra bullets of shame that already riddled my bones—the fear of what others would think if they knew I committed the mortal sin of sex before marriage. Shame sucked the breath out of me and lay tight on my throat and chest. If there was a way to get out of this predicament without being thought of as a slut for all eternity by my classmates at Regina Dominican High and the nuns and priests at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church, I was eager to live the lie. I imagined if they found out, I would be a castaway, a leper, friendless, shunned and ignored, banned to a lifetime of lonely regret.

Giving my baby away was not easy to forget. As an adult, the resulting grief cloaked my spirit. When I saw a baby being born on TV, I cried. When I saw a mom at the mall carrying her newborn in a pack close to her chest, I was brought to tears. When my first child was born that was truly my own, I loved her so, yet sobbed for the one I had lost and began to wonder how I could have given away my own child to a stranger.

In writing the words of my story, I try to make sense of this traumatic childhood sorrow. It continues to be a dynamic process, like riding an escalator. Sometimes I climb up as the steps move, adding speed to my journey. In less productive times I shuffle backward, against the natural momentum, afraid to move ahead. This is when I stuff the rising emotions of sadness and regret, not allowing myself to feel, causing a flat numbness. During these times of procrastination I could spend hours writing early childhood anecdotes that really had nothing to do with my story; I was not yet ready to get to the heart of the matter. The upward part of the journey is when I write what matters and become reacquainted with my teenage self. During these times of grace I uncover compassion for the child in me and I find forgiveness. Regardless of my steps up or down, I continue my quest for the top in this, my sixtieth year of life.

When I first started writing, I navigated through a fog of lost memories, adept at having stuffed them away. But as the sun clears the morning fog, one by one the memories unfolded as I wrote, until the picture was repainted.

This one, an indelible part of me:

As we stood outside the Salvation Army Home for Unwed Mothers, with the trunk open and the items being gathered for my extended stay, my father took each of my books, including my cherished white leather prayer book, and, using his Parker fountain pen, scratched my last name from the inside covers of each one. I would be referred to as Judy L. during my stay. Then, my father gave his last bit of advice, “You’ll forget about this, Judy, and you’ll never have to speak of it to anyone again. Later, you may get married, but there’s no reason to even mention this to your husband.”

AD

F

ISHING

- 1980

AD

, J

EFF

, J

UDY

, M

OM

1956