Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City (35 page)

Read Strolling Through Istanbul: The Classic Guide to the City Online

Authors: Hilary Sumner-Boyd,John Freely

Tags: #Travel, #Maps & Road Atlases, #Middle East, #General, #Reference

This, then, is the great külliye of the Süleymaniye. Surely there can be in the world few, if any, civic and religious centres to compare with it in extent, in grandeur of conception, in ingenuity of design, or in the harmony of its parts.

S

İ

NAN’S TÜRBE

Before we take leave of the Süleymaniye, we might stop for a moment at the tomb of the architect, which stands in a little triangular garden at the north-western corner of the complex. Sinan lived on this site for many years and when he died he was buried in his garden, in a türbe which he had designed and built himself. Fom the apex of the triangle radiate the garden walls, enclosing the open marble türbe. An arcade with six ogive arches supports a marble roof which has a tiny dome over the sarcophagus; the latter is of marble with a turbaned tomb stone at the head. Outside the türbe are several other graves, presumably of Sinan’s wife and children, but unfortunately there are no inscriptions.

On the south wall of the türbe garden there is a long inscription by Sinan’s friend, the poet Mustafa Sa’i, which commemorates the architects accomplishments. Mustafa Sa’i also wrote of Sinan in his

Tezkere-ül Ebniye

, and from this and other sources we can piece together the life-history of this extraordinary genius. Sinan was born of Christian parents, presumably Greek, in the Anatolian district of Karamania in about 1490. When he was about 21 he was caught up in the

dev

ş

irme

, the annual levy of Christian youths who were taken into the Sultan’s service. As was customary, he became a Muslim and was sent to one of the palace schools in Istanbul. He was then assigned to the Janissaries as a military engineer and served in five of Süleyman’s campaigns. In about 1538 he was appointed Chief of the Imperial Architects, and in the following year completed his first large mosque in Istanbul, Haseki Hürrem Camii. In the following half-century he was to adorn Istanbul and the other cities of the Empire with an incredible number of mosques and other structures. In the

Tezkere

, Mustafa Sa’i credits Sinan with 84 mosques, including 42 in Istanbul, as well as 52 mescits, 63 medreses, seven Kuran schools, 22 türbes, 18 imarets, 20 kervansarays, three hospitals, 35 palaces, eight storehouses, 52 hamams, six aqueducts and eight bridges, a total of 378 structures of which 86 still remain standing in Istanbul alone. And although he was in his 50th year when he completed his first mosque in Istanbul, this renaissance man got better as he grew older and was all of 85 when he completed his crowning masterpiece, the Selimiye mosque in Edirne. He did not pause even then and in the years that were left to him he continued his work, building in that period, among other things, a half-dozen of Istanbul’s finer mosques. Koca Mimar Sinan, or Great Sinan the Architect, as the Turks call him, died in 1588 when he was 97 years old (100 according to the Muslim calendar). He was the architect of the golden age and his monuments are the magnificent buildings with which he adorned this city.

Galata Bridge

to

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

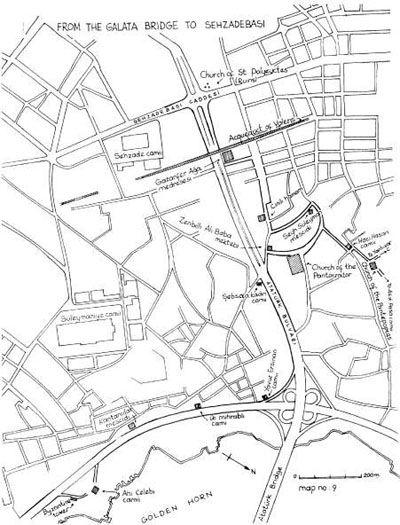

Once more we begin our stroll at the Galata Bridge, this time to begin walking up the shore of the Golden Horn before heading up hill to the district called

Ş

ehzadeba

ş

ı

, just to the north of the

Ş

ehzade mosque. The first part of our stroll takes us through the oldest market area of the city, a rough and colourful quarter that is stubbornly resisting attempts to modernize it.

THE PRISON TOWER

The part of the market district just above the Galata Bridge and between the shore road and the Golden Horn is known as Zindan Kap

ı

, or the Prison Gate. This waterfront quarter was one of the oldest and most picturesque neighbourhoods in Istanbul, but in the early 1970s almost all of its buildings were demolished in a project designed to create parks along the shore of the Golden Horn but which here resulted only in a scabrous parking lot. One of the few surviving monuments is an ancient tower behind a late Ottoman commercial building known as the Zindan Han. This is by far the largest of the few surviving defence towers of the medieval Byzantine sea-walls along the Golden Horn. The tower was for centuries used as a prison (in Turkish,

zindan)

by both the Byzantines and the Ottomans, particularly for galley slaves. Within the tower, known to the Venetians as the Bagno, is buried a certain Cafer Baba, who, according to legend, came to Constantinople as the envoy of Harun al-Rashid to the Empress Eirene (r. 797–802), but was here imprisoned and died; his grave was rediscovered and restored after the Conques and is to this day much venerated. According to Evliya Çelebi: “Cafer Baba was buried in a place within the prison of the infidels, where to this day his name is insulted by all the unbelieving malefactors, debtors, murderers, etc. imprisoned there. But when (God be praised!) Istanbul was taken, the grave of Cafer Baba in the tower of the Bagno became a place of pilgrimage which is visited by those who have been released from prison and who call down blessings in opposition to the curses of the unbelievers.” The tower was restored in 1990 and the supposed grave of Cafer Baba on the ground floor of the tower was opened to the public as a Muslim shrine.

Just beyond the Zindan Han are the shattered remnants of an arched gateway from the medieval Byzantine period. The identity of this gate is uncertain, but in early Ottoman times local Greeks referred to it as the Porta Caravion (the Gate of the Caravels), because of the large number of ships which were moored at the pier nearby, the ancient Scala de Drongario. This pier, known as the Yemi

ş

Iskelesi, or Dried Fruit Pier, was still in use up until the mid-1980s, but then it was demolished along with the rest of the Zindan Kap

ı

quarter, which was for many centuries the principal fruit and vegetable market of the old city but is now only a fading memory.

THE MOSQUE OF AH

İ

ÇELEB

İ

Passing the gateway, we soon find ourselves in front of an ancient mosque, Ahi Çelebi Camii. This mosque was founded at an uncertain date by Ahi Çelebi ibni Kemal, who was Chief Physician of the hospital of Fatih Mehmet and who died in 1523 while returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca. The building is of little architectural interest, aside from the fact that it was apparently restored at one point by Sinan. Its principal interest to us is its association with Evliya Çelebi, whose

Seyahatname

, or

Book of Travels

, we have so often quoted in our guide. One night in Ramazan in the year 1631, when Evliya was 20 years old, he fell asleep and dreamt that he was in the mosque of Ahi Çelebi. While praying there, in his dream, he was astonished to find the mosque fill up with what he described as “a refulgent crowd of saints and martyrs,” followed by the Prophet, who gave him his blessings and intimated that Evliya would spend his life as a traveller. “When I awoke,” writes Evliya, “I was in great doubt whether what I had seen was a dream or reality, and I enjoyed for some time the beatific contemplations which filled my soul. Having afterwards performed my ablutions and offered up the morning prayer, I crossed over from Constantinople to the suburb of Kas

ı

m Pa

ş

a and consulted the interpreter of dreams, Ibrahim Efendi, about my vision. From him I received the comfortable news that I would become a great traveller, and after making my way through the world, by the intercession of the Prophet, would close my career by being admitted to Paradise. I then retired to my humble abode, applied myself to the study of history, and began a description of my birthplace, Istanbul, that envy of kings, the celestial haven and stronghold of Macedonia.” But such beatific visions are denied to the modern traveller, who must now resume his stroll through Stamboul, heading up the main highway that leads along the bank of the Golden Horn between the two bridges.

KANTARCILAR MESC

İ

D

İ

, KAZANCILAR CAM

İ

İ

, AND SA

Ğ

RICILAR CAM

İ

İ

As we walk along the left side of the avenue we pass in turn three little mosques which are among the very oldest in Istanbul, all of them built just after the Conquest. The first of these that we come to is Kantarc

ı

lar Mescidi, the mescit, or small mosque, of the Scale-Makers, named after the guild whose artisans have had their workshops in this neighbourhood for centuries. This mosque was founded during Fatih’s reign by one Sar

ı

Demirci Mevlana Mehmet Muhittin. It has since been reconstructed several times and is of little interest except for its great age.

The second of these ancient mosques which we pass, about 250 metres beyond the first, is called Kazanc

ı

lar Camii, the mosque of the Cauldron-Makers, here again named for one of the neighbourhood guilds. It is also known as Üç Mihrabl

ı

Camii, literally the mosque with three mihrabs. Founded by a certain Hoca Hayreddin Efendi in 1475, it was enlarged first by Fatih himself, then by Hayreddin’s daughter-in-law, who added her own house to the mosque, so that it came to have three mihrabs, hence its name. The main body of the building, which seems to be original in form though heavily restored, consists of a square room covered by a dome resting on a high blind drum, worked in the form of a series of triangles so that pendentives or squinches are dispensed with. In the dome are some rather curious arabesque designs, not in the grand manner of the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries nor yet in the degenerate Italian taste of the nineteenth; they are unique in the city and quite attractive both in design and colour. The deep porch has three domes only, the arches being supported at each end by rectangular piers and in the centre by a single marble column. The door is not in the middle but on the right-hand side, so as not to be blocked by the column; this arrangement, too, was common in the preclassical period, but there are only a very few such examples in the city. To the south of the main building is a rectangular annexe with a flat ceiling and two mihrabs; it is through this annexe that we enter the mosque today. According to one authority this section is wholly new; possibly, but as far as form goes, it might well be the dwelling house added by Hayreddin’s daughter-in-law.

The third mosque is found about 150 metres farther on, a short distance before the Atatürk Bridge. This is called Sa

ğ

r

ı

c

ı

lar Camii, the mosque of the Leather-Workers, which guild once had its workshops in this area. The building is of the simplest type, a square room covered by a dome, the walls of stone. It was restored in 1960 with only moderate success. But although the mosque is of little interest architecturally, its historical background is rather fascinating. For one thing, this is probably the oldest mosque in the city, founded in 1455 by Yavuz Ersinan, standard-bearer in Fatih’s army during the final siege of Constantinople. This gentleman was an ancestor of Evliya Çelebi; his family remained in possession of the mosque for centuries, living in a house just beside it. Evliya was born in this house in about 1611 and there, 20 years later, he had the dream which changed his life (and immeasurably enriched our knowledge of the life of old Stamboul). The founder himself is buried in the little graveyard beside the mosque. Beside him is buried one of his comrades-in-arms, Horoz Dede, one of the fabulous folk-saints of Istanbul. Horoz Dede, or Grandfather Rooster, received his name during the siege of Constantinople, when he made his rounds each morning and woke the troops of Fatih’s army with his loud rooster call. Horoz Dede was killed in the final assault and after the city fell he was buried here, with Fatih himself among the mourners at his graveside. The saints grave is venerated to this day.