Strangewood

Authors: Christopher Golden

Tags: #Psychological Fiction, #Boys, #Fantasy Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction, #Divorced Fathers, #Fathers and Sons, #Fantasy & Magic, #General, #Fantasy, #Horror & Ghost Stories, #Children's Stories, #Authorship, #Children of Divorced Parents, #Horror, #Children's Stories - Authorship

by Christopher Golden

Copyright 1999 by Christopher Golden

This book is a work of fiction. All characters, events,

dialog, and situations in this book are fictitious and any resemblance to real

people or events is purely coincidental. All rights reserved. No part of this

book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of

the author.

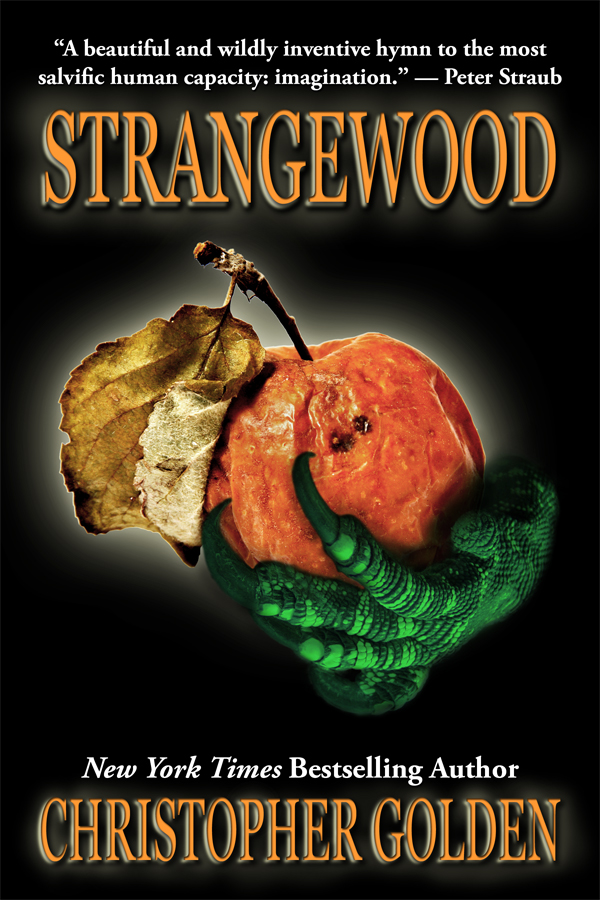

Cover Art by Lynne Hansen

Book Design by Lynne Hansen

http://LynneHansen.zenfolio.com

Art graciously contributed by:

Von-Chan - http://von-chan.deviantart.com

Guavon-Stock - http://guavon-stock.deviantart.com

For more information, contact:

[email protected]

Visit

http://www.ChristopherGolden.com

"If Clive Barker had gone

Through the Looking Glass

,

he might have come up with something as imaginative and compelling as

Strangewood

."

— Kevin J. Anderson, author of

Dune: House Harkonnen

"

Strangewood

the novel is a daring and thoroughly

engrossing blend of wonder and adventure, terror and tenderness. Strangewood

the place is what Oz might have been if L. Frank Baum had grown up on a steady

diet of Stephen King." — F. Paul Wilson, author of

The Keep

"A fascinating read." —

Cemetery Dance

Magazine

For Connie.

Without you, the sun would never rise.

Introduction by Christopher Golden

Connect With Christopher Golden Online

Other Works by Christopher Golden

By now you all know the number one question writers most

dread hearing . . . which is consequently the number one question we are asked.

Where do we get our ideas?

There are two types of people who ask this question: those

who’d like to find out where the ideas come from so they can go there and pick

up a few, and those who think I’m absolutely insane because of the weird shit I

write.

Most of the time, I push the question off. The truth is,

most ideas are bits of inspiration and information I’ve cobbled together over

the course of months or years, things that are completely unrelated but which

end up revealing themselves as connected, if only I’d work a little harder at

filling in the blanks. These are ideas that are built, not found.

Recently, I’ve actually dreamed a couple of book ideas, but

I don’t talk about that much because I think it pisses people off. It means I

didn’t work for them. That’s not precisely true — dreams don’t make a lot

of sense and so they have to have the blanks filled in as well — but

still, it makes it sound easy.

Then there’s the “eureka” idea. I’ve had three of those

revelatory moments thus far in my career and I’ve been very pleased with the

results each time.

Strangewood

came about that way.

I had recently been to a convention where Clive Barker was

urging the writers in the audience not to restrict their own imaginations. He

felt that the worst thing a writer could do was to have an idea and then rein

it back, tell themselves it was too wild.

The timing of this was vital.

Shortly after I returned from that convention I was being

interviewed for a magazine by my friend and later colleague Hank Wagner. My

son, Nicholas, was perhaps three at the time, and what we’ll call a

Winnie-the-Pooh aficionado. Which is to say we had more than two dozen Pooh

video tapes that we watched round the clock.

I love Winnie-the-Pooh. Always have. I read the original

Milne to my kids when they were very small. But good God, there’s only so much

of anything one man can take. I told Hank that I had watched so much Pooh that

I’d reached the point where I’d love to see armed warriors on horseback ride

down into the Hundred Acre Wood, skin the little bastards, and nail their pelts

to trees.

Strangewood

was born in that moment. The whole thing.

Certainly there were details that came later, some of them intrinsic to what I

perceive as the success of the story. Also, as I wrote, I was greatly

influenced by a wonderful short story I had read years before called “The Power

of the Mandarin,” by the cartoonist, writer and gentleman, Gahan Wilson.

But for all intents and purposes, that was it. The light

bulb. The eureka idea.

So for those of you who ask that question, you now have an

answer, at least where this story is concerned.

What a relief to find that the mad imagery that had come

into my head at that moment was vivid enough not only to propel me through the

book, but to carry others along with me. I asked a handful of writers I knew to

have a look at it, some of them friends and others friendly acquaintances, and

I waited with trepidation for their replies. You can not possibly imagine the

relief and elation I felt when the feedback began to arrive from authors who

had always had my deep and abiding respect: Peter Straub, F. Paul Wilson,

Graham Joyce, Kevin J. Anderson and others lent their voices in support. I felt

blessed and, also, like the luckiest bastard on Earth. I thought I ought to

hurry up and get the book out before they changed their minds.

Upon publication, readers embraced the book as well. The old

adage about not being able to please everyone is true, of course, but by and

large those who ventured into

Strangewood

with me that first time around

seemed to have been more deeply affected by it than the readers of anything

else I had ever written. I received countless e-mails asking for more

adventures in Strangewood . . . and who knows? Perhaps, one day. In fact,

there’s a story in my head already, a sort of eureka junior, and I even have a

title . . . but that’s for another time.

Unfortunately, word didn’t get out quickly enough, or widely

enough and as so often happens,

Strangewood

slipped out of print. But

the e-mails kept coming. People continued to ask about it. And my editor, Laura

Anne Gilman, continued to champion this odd little story.

So here we are, back again, hopefully for a much longer run

this time.

I’ve often referred to

Strangewood

as the book with

which I “grew up” as a writer. Sort of ironic, I think, given that it concerns

children’s literature and the sorts of characters that populate the landscapes

of such works. Nevertheless, I still think of it that way. The dark fantasy

novels I’d previously written were about action and ideas. Don’t get me wrong,

there’s something to be said for that.

The Shadow Saga

will always be

near and dear to my heart and I intend to keep visiting that world. But I found

with

Strangewood

that I had other types of stories in me.

Instead of action and ideas,

Strangewood

is about

characters and situations. While working on it, I began to think of it — and

to refer to it — as a domestic dark fantasy. To me, that meant that it

was about the people first, about an ordinary group of people with ordinary

problems. In this case, about Thomas and Emily Randall, recently divorced, and

their troubled son Nathan. It was about extraordinary things happening to these

ordinary people, and the consequences that resulted from that. It was about

fatherhood and divorce, about creation and neglect, and about how we have to

negotiate emotionally when love falters.

See, and you thought it was just about talking crows and

pissed off saber-toothed tiger men.

Strangewood

remains my favorite of all my books.

I hope you enjoy your journey there.

Forgive me, please, if I also hope that you don’t emerge

entirely unscathed.

Christopher Golden

Bradford, Massachusetts

In the traditions of the Fantastic, the motif of the Woods

looms large. Christopher Golden’s

Strangewood

emerges, trailing clouds

of glory, from those very traditions. The Woods is a place of archetypal force.

The writer who invokes the power of the greenwoods knows that the stakes are

high and the list of antecedents long. In fact it would take a book on its own

to chart the treatment of the theme and the antecedents are too rich to

catalogue here.

In fact I ought to write it, though I know I won’t because

it would take too long. But if I did I could talk about how fairy tale

tradition locates so many of its glorious stories —

Hansel and Gretel

,

Babes In The Wood

,

Red Riding Hood

, just to name three — in

the Woods for very particular reasons. Or why

A Midsummer Nights Dream

by ol’ Will Whatsisname has to be located in the Forest of Arden; or about Kipling’s

Man-Cub, just like Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan, being raised in the jungle by

animals.

In their brilliant cataloguing of Fantasy motifs the

encyclopaediasts Clute & Grant generated the phrase

Into the woods

to denote the process of transformation or passage into a new world signaled by

entering woods and forests. It is very often that, but it’s actually even more

specific, and certainly more than the usual fantasy portal to transformation. For

the Woods is a very literal place of both dark and light. Of beaten pathways

and uncharted zones. Of twists and turns. A place where you may encounter

strange allies or enemies masquerading as friends. It is the primal locus of

fear and wonder. In other words, in the fiction of the Fantastic, the Woods is

so often the psychic correlative to the condition of Childhood.

The Woods stands in for the budding consciousness of the

child, the individuation of character, and the ultimate emergence from the

woods represents the passage out of childhood. Or to put it another way, the

passage out of unconsciousness and into self-consciousness. For example, CS

Lewis launches the children of his

Narnia

sequence into the woods before

having them emerge as heroes. But — and it’s a big but — the

protagonists do not have to be children. More recently and in works more

complex, varied (and dare I say superior to Lewis), Charles De Lint (

Greenmantle

),

Rob Holdstock (

Mythago Wood

) and Ramsey Campbell (

The Darkest part of

The Woods

) — just to name a few — explore the awe-inducing presence

of the Greenwood and its role in the human psyche.

Christopher Golden takes this rich tradition and braids it

beautifully with another pattern recognisable to the connoisseur of the

Fantastic concern: that of the artist (in this case a writer) haunted by his

own creations, Stephen King’s

The Dark Half

and Peter Straub’s more

recent In

The Night Room

being too very fine examples of the species. All

writers work with antecedent forms. What separates the mere copyist from the

creator (and Christopher Golden along with all the authors mentioned above is a

superb creator from antecedent form) is the originality of vision that makes a

story worth recasting in a persuasive new form.

In the case of

Strangewood

, what Christopher Golden

does is to complicate all of the above by positing the question of the

relationship between Childhood, Creativity and the Imagination. These are

indeed haunting themes for all writers, especially authors of the Fantastic. There

is, after all, a relationship between vulnerability and the imagination. What

can be more vulnerable than the image of a small child in the woods? And what

can be more clever than that device by which Christopher Golden brilliantly

contrives to have not only the child, Nathan, at risk in the woods; but also to

render the adult hero of the narrative, Thomas, as simultaneously the

responsible father and the original child, the “Our Boy” of Strangewood.

It’s a master-stroke of story-telling, and one which

elevates

Strangewood

, pushing it into that prized place in which the

story is mysteriously larger than itself.

So there is in

Strangewood

an exploration of the

complex relationship between a writer’s family dynamics, childhood,

imagination, creativity and children. All of this is offered in a fascinating

double narrative, where Strangewood reaches out, root and branch, to impact

upon the world of its creator.

Thomas, the protagonist of the story, is an author who

suffers an extreme responsibility for the things he has created in the

children’s novels he writes. A terrible revenge is visited on his own child. The

novel links a disintegrated marriage, which of course threatens the happiness

of the child Nathan, with the internal collapse of the Fantasy world — Strangewood

— created by the author Thomas. The question is whether the crisis is

precipitated by the flawed nature of Thomas, or by the crisis of his marriage;

but whichever it is, in this case “the sins of the father are visited on their

sons.”