Storm's Thunder (30 page)

Authors: Brandon Boyce

I hear Merle try to wrangle his customers back to the bar. “You heard the sheriff. Get back inside and I'll buy you cocksuckers a drink.” But the promise of a shootout draws men's attention like flies to a dead cow, even under the threat of free whiskey.

A drunken voice yells out, “Send the halfbreed in after 'em, Sheriff. No sense in gettin' you'self kilt.” I want to turn around, but do not.

Elbert Pooley's wagon lies jackknifed in the middle of the road. His two mules, spooked by the explosion, strain and whinny against the reins, dragging the wagon in a slow-moving arc. Elbert is down with the mules, holding the bridle of one and trying to grab the other. “Take cover, Elbert. Leave them mules be,” I say to him.

“Their legs will snap!” Elbert pleads, trying not to cry. I take the bridle of the bucking mule and calm her.

“Cut 'em free then.” I know by Sheriff's tone that this is meant for me and I start pulling at the leather. Elbert stops dithering and gets busy on the other mule. Sheriff takes a knee behind the overturned wagon and peers around at the bank door directly in front of him. I get my mule free, slap her hindquarter, then set about helping Elbert, who is making a mess of it.

“This one here,” I say, unfastening the proper line. The mule pulls free and I put Elbert's hand up to her bridle.

“God bless you, son. God bless, you!” Elbert says, leading one mule off with him to chase after the other.

I glance over at the bank, squat down behind Sheriff. “Two geldings hitched up out front.”

“And neither one spooked,” Sheriff says. “I suspect they have seen this before.”

“Not much cover here with this wagon.”

“No, but it will have to do.” Sheriff turns his head toward me, but not all the way, keeping one eye on the door. “You best go on. Get over to the post office. Tell Bertram to wire the governor's office. Tell him to send marshals. Then go fetch Doc. We are going to need him for sure.” Sheriff sees that I do not want to leave him so he says, “I will be all right, Harlan. Now go on.”

I stay crouched and run off down the alley opposite the Loan and Trust. At the end of the building I turn left and flank Main Street from the alley behind the chemist's. I enter the post office through the back door, all the while hoping I do not hear a gunshot, or worse, a scream. I arrive at the front of the post office but find no one behind the counter. “Anybody here?” I ask.

“We're down on the dang floor and I suggest you do the same.” The voice of Bertram Merriman, the postmaster, sounds far away. I turn toward the window and see Jasper Goodhope on all fours behind the writing desk, still clutching the letters he came in to post. Through the window I have a clear view of the Loan and Trust. The upturned wagon is off to the left and I can just see the edge of Sheriff's boot behind it.

“Who is it?” Jasper asks. “Is it the Snowman, you reckon?”

“Don't know.” I crouch down to where the glass meets wood. All at once a man kicks up a horse and a second later that same bandit who followed the safe outside comes barreling around from the back of the bank on a palomino he must have had tied up there. Clever thieves. Keep the horses spread out. He is at full gallop when he hits the street. He cuts hard to the left, rushing away from the sheriff. The bandit fires his Colt three times, hitting the wagon twice. He holds the booty in his rein hand. A fine rider. Even better with the gun. Sheriff rises and fires off two shots from his Spencer, but the palomino knows what guns mean and has her rider a hundred yards off before Sheriff can get a bead on him.

I see the door of the Loan and Trust swing open, revealing darkness inside and little else. Sheriff swings the Spencer around toward the door. “You come out slow with your hands where I can see them.” Sheriff's voice echoes through the window. Then silence. I hear Jasper Goodhope's heart pounding beneath his clothes. Sheriff rises a little, which I do not like. But he might see something I cannot.

The dark interior of the bank holds no clue, until a muzzle flash barks out from it, biting an apple-size chunk from the wagon's flank. Sheriff falls to his side, hit, but not dead. He regains the Spencer, leans around the side of the wagon, pounds a half dozen rounds into the dark void and through the walls. The Spencer clicks empty and he grabs his right-side Colt. From the darkness comes a single shot that pierces the wagon like it was not there. Sheriff slumps.

Two men charge out of the bank. The barefaced man fires deliberately toward the saloon, discouraging any vigilante sniping. The one covered in blue leaps from the railing and lands in the saddle of his gelding before positioning his compatriot's horse for a similar mount. He calls out to the town, but I swear his eyes fall on me. “Anyone riding after us gets the same.” Then he kicks up the gelding and they are gone.

I am already halfway to Sheriff. I turn him overâhis green eyes seem to look

through

me. But then they focus, finding me, recognizing me.

through

me. But then they focus, finding me, recognizing me.

Sheriff touches my face for only the second time in my life. “It was the Snowman. I seen him with my own eyes. Snowman, sure as day.” He tries to say something else, then stops, exhausted.

“We will get you to Doc's. I swear it.” I watch the blood drain from his face. He starts to look through me again, all the way to heaven. I try to lock eyes with him, but I cannot see his face through all the damn water.

CHAPTER TWO

The last of the mourners disappears down the hill trail heading back to town. My Sunday shirt is soaked from shoveling. I take a seat beneath the shade of the big pinyon pine and steal my first smoke of the day. Even with three of us laying into our spades, it took a quarter hour to fill in the berm of fresh earth that holds the sheriff.

The widow was laid to rest earlier this morning, in the churchyard. Padre spoke a good piece beforehand, carrying on about damnation for the offenders and the broken morality of the West. He had to lump his lamentations for Sheriff and Widow Daubman into a single go because he knows most rightly that assembling the citizenry of the Bend twice in one day, even if the second time is for their beloved sheriff, is beyond the miracles of the Almighty.

From the churchyard the townsfolk followed the wagon carrying Sheriff's casketâa handsome, cherrywood design donated with respectful condolences from the mortuary in Heavendaleâin a slow-moving processional down Main Street and up the half-mile trail to Sheriff's final resting place. The heat stirred a few sighs of vexation, which stern eyes quickly silenced.

All of Caliche Bend had come to honor its fallen lawman. All except Frank Wallace, who remains bedridden on Doc's orders, and Mrs. Wallace, who must be half deaf herself the way poor Frank shouts everything now. Frank Wallace has come along in the two days since the Snowfall, when the search party, headed by me, found him mumbling nonsense in Big Jack Early's cornfield an hour after dusk. My nose led the way, the smell of charred flesh and urine-drenched wool lighting him up like a beacon.

Frank Wallace is lucky. Whatever shard of metal dismembered him was hot enough to cauterize what it left behind. Otherwise he would have bled out and the smell that drew me to him would have been the same one that attracts the vultures.

Doc worked on him through the night while the padre convened a vigil of the widows that prayed and wailed by candlelight until dawn. When Frank Wallace opened his eyes just before noon the next day, he was, save for his damaged hearing, in remarkable possession of his facultiesâso much so that two hours later he was able to holler out his account of the robbery from his bed.

At the mayor's insistence, a man from Western Union was brought in to serve as scribe, scribbling down every word. I and a dozen other folks gathered outside Frank's window to hear the account, while Mayor Boone stood bedside, nodding solemnly at the appropriate junctures. When Frank Wallace, hoarse and weak of body, finally concluded his narrative, Boone anointed himself official witness by certifying the written record with his signature.

“Well done, Frank. They will hang by this, for certain,” Walter Boone said, collecting the ream of parchment the moment the ink had dried.

Tending to personal matters in Santa Fe at the time of the murders, Boone had received the news by telegram at his hotel and returned on the first train. He had not yet been home when he strode out of Frank Wallace's house carrying the pages in his valise. The sight of his steamer trunk aboard the wagon, hastily packed no doubt, confirmed his direct arrival from the depot.

* * *

The fine headstone, spared the vicious glare of an unfettered sun by the broad branches of the pinyon, sends its gentle warmth through my waistcoat as I lean against it. I know it is the warmth of Sheriff and of Mrs. Pardell next to him, beneath a fathom of New Mexico dirt. My finger drifts languidly over the stonecutter's work. The Pardell name I have seen enough times to know the letters. But the latest amendment, D-A-V-I-D, chiseled this very morning, marks what can only be Sheriff's Christian name, while the fresh numbers recall a life that began some fifty years ago and ended, by a lone slug from a murderer's forty-four, in 1-8-8-7.

“If I go before my dear Catherine, be sure I am buried here.” Sheriff said those words to me after the huge Mexican bighorn gave the place to us. I'd spotted the big male among the ewes, stone still, nearly invisible against the ashy rock slope. His eyes had me in his stare. I nodded just the slightest to tell Sheriff I had something.

“I don't see him,” Sheriff whispered.

“He's there,” I said, even softer. “Just below that gray boulder.” A half minute passed before Sheriff let out a small breath that told me he saw the ram too.

Sheriff brought up the Spencer and fired. The ram buckled, then recovered and skipped off. The ewes scattered. With Sheriff clamoring behind me, I tracked the ram for an hour, following the scant blood drops and faint click of his hooves over the rocks until the animal could run no more. He knelt down and waited for us. When we found him he was still breathing, his eyes open and at peace. This was a few yards from where Sheriff now lies. The big ram wanted us to have this placeâwe had earned it. He stayed alive long enough to make sure we understood.

I thanked him and with my knife passed him on without suffering. I joined Sheriff at the edge of the overlook. “My God,” Sheriff said. “What a view.”

As I stare out at it now, the panorama of the landscape appears much as it did on that day three years ago when we discovered it. The whole of the valley stretches in both directions to the horizon. To the south, the white houses and fertile fields of Agua Verde hug the banks of the river. The snaking, emerald water holds its hue even in the full glare of the sun. Clear air makes the town appear much closer than its true distance of twelve miles, but to anyone in Caliche Bend, the bloom of prosperous green that is Agua Verde lies across a dusty, inhospitable ocean of busted claims and broken dreams.

Our neighbors to the north seem equally unreachable. The town of Heavendale, with its mines running rich with copper and turquoise, shimmers regally from its perch atop the foothills of the valley's northward rising edge. Eight hardscrabble miles of high desert separate it from the Bend, which, after crossing, greet the weary traveler with a sign that reads:

HeavendaleâCloser to God

.

HeavendaleâCloser to God

.

The Sangre de Cristo range rises like a spine to the west, straight across from me, bridging the whole of the valley and pinning those who live in it behind an impenetrable wall of cragged peaks, perilous ravines, and general misery. The Sangres swallow a man whole. They can wilt the heartiest frontiersman or freeze an entire mule train in its tracks. Billy goats starve in the stingy landscape while the punishing winds have been known to grind adobe huts into dust. Even the strongest Navajo hunters stay away from all but the lowest ridgesâand even then, they venture into the Sangres only for a guarantee of a big reward, perhaps to finish off a wounded elk that could feed a village for a week. The Sangres were not put here to be crossed. They are here to be respected.

The valley thrives at its extremities, protects its flanks, and in its barren and forgettable crotch, offers up the Bend. I tune my ears to the sounds of its discontent. I can almost hear the arguments brewing at the meeting hall, where this minute strident voices debate the proper course of action. It is a circus of frustration I will step into soon enough. But for now, my eyes fix on the Sangres.

A wildfire, when it happens, coats the sky for miles in a billowy, ashen cloud. And a controlled brush burn or the clearing of timber leaves a choking thumb smudge of black. But the thin gray string of vapor rising from the pass directly across from me now indicates none of those things. From the Bend I would not see this spindly column of smoke at all. Only here in the foothillsâblessed by the sharp eyes the Spirits gave meâam I of sufficient altitude to detect it. Perhaps Sheriff guides me still, or through him, the bighorn. But the meaning of the smoke is clearâa mile or two into the Sangres, in a pass the Navajo call the Gulch of No Place, a campfire burns.

I pull hard on the last of my cigarette and stub it out on the ground. Then I steel myself for the long walk back to town. There will be no sleep for me tonight.

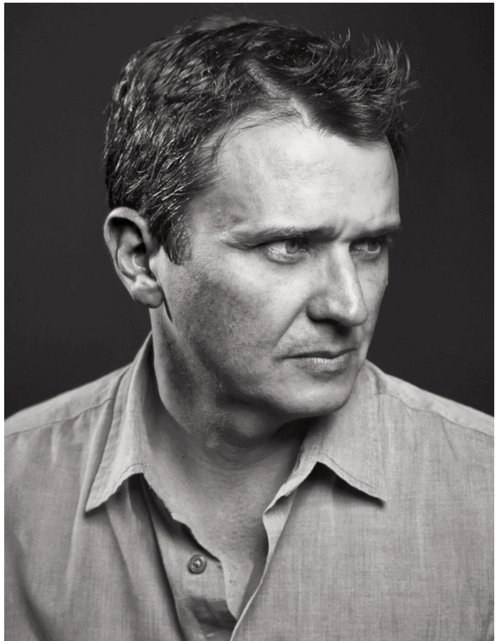

Randall Slavin

B

RANDON

B

OYCE

was born in Staunton, Virginia, and received a B.A. in English from California State University, Los Angeles. An accomplished screenwriter, his films include

Apt Pupil

,

Wicker Park

, and

Venom

. His short fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals. His first novel,

Here by the Bloods

, was published in 2014.

Storm's Thunder

is his second novel. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife.

RANDON

B

OYCE

was born in Staunton, Virginia, and received a B.A. in English from California State University, Los Angeles. An accomplished screenwriter, his films include

Apt Pupil

,

Wicker Park

, and

Venom

. His short fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals. His first novel,

Here by the Bloods

, was published in 2014.

Storm's Thunder

is his second novel. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife.

Other books

Love, Lies, and Murder by Gary C. King

End Zone by Tiki Barber

Rocky Mountain Angels by Jodi Bowersox [romance]

Smooth Operator by Emery, Lynn

Nightmare by Joan Lowery Nixon

The Memory of Death by Trent Jamieson

Nine Days by Toni Jordan

The Element by Ken Robinson

The Steel of Raithskar by Randall Garrett

Paranormal Curves (BBW Collection) by Curvy Love Publishing