Stories of Faith and Courage From World War II (19 page)

Read Stories of Faith and Courage From World War II Online

Authors: Larkin Spivey

Tags: #Religion, #Biblical Biography, #General, #Spiritual & Religion

Dear friends, do not be surprised at the painful trial you are suffering, as though something strange were happening to you. But rejoice that you participate in the sufferings of Christ, so that you may be overjoyed when his glory is revealed.

—1 Peter 4:12–13

A Jubilant Mood

The Canadian ship

Kamsack

had been through a rough deployment. Days of mountainous seas and freezing rain had sapped the crew’s strength and spirit. Sent to rescue a torpedoed ship under the worst possible conditions, they had labored and suffered at their duty stations aboard the small corvette. Frank Curry described his feelings as this ordeal came to an end on Christmas Eve:

We staggered into Sydney harbour this Christmas Eve, feeling pretty good about accomplishing our mission. What a feeling to tie up securely to a jetty where everything is still—the crew in a jubilant mood, and I am no exception. Make and mend in the afternoon and we spent it cleaning our mess decks. Duty watch for me—on Quartermaster from 20002400, and I saw Christmas Day come in from the frozen gangway. Celebrated by taking a hot shower and climbing into my hammock at 0100.

114

There are few satisfactions like that of successfully completing a difficult job. This wartime sailor ushered in Christmas Day in pretty miserable conditions on a small and battered ship, but he nevertheless knew that he was safe and warm and that he and his fellow crewmen had accomplished a difficult task under almost impossible conditions.

One of my mother’s favorite sayings was, “Happiness is a byproduct of duty well performed.” Her point was that happiness is not found as an end in itself. It finds us when we do what we’re supposed to do. This was certainly the case with these sailors of the

Kamsack

. In Colossians Paul exhorts us to work at our duties with all our hearts, recognizing two things: first, that this kind of effort will be rewarded by the Lord, and second, that we are really serving Jesus Christ with our work (Colossians 3:23–24). If we can remember this as we diligently do our jobs, happiness will indeed be the wonderful byproduct of our work!

Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for men, since you know that you will receive an inheritance from the Lord as a reward. It is the Lord Christ you are serving.

—Colossians 3:23–24

Was God There?

In 1943 George Hurley wrote a poetic description of the physical, mental, and spiritual hardships of shipboard life in the Arctic. There are seventy-eight verses in this work, and several touch on the issue of God’s presence in this remote corner of the world.

Rosary beads are my frozen tears / Will they thaw in future years?

Valor so common not recorded in history / Ships just vanish, a Russian mystery.

Dear friend, Jesus, to You I call / Help your lambs before we fall

I can’t promise I’ll be good tomorrow / But the Bible says you watch the sparrow.

No one is talking, I hear no voices / Am I spared? Has God made his choices?

Why did he leave me, I’ll never know / But it looks to me like the end of the show.

Drink a toast to the bastardly sons / Don’t mention the battle we surely won

God took a vacation, left us alone / Out in the ocean, so white with foam.

Oh we cursed you, old ship, you were so slow / But you took us there, where no one would go

Brought us back to the American shore / No one could ask for anything more.

115

It’s ironic and very human that the seaman would credit his ship for a safe return home, but accuse God of abandoning him. As an unbeliever, I have done the same thing in times of stress. I wondered where God was, even while marveling at the selflessness of young Marines helping each other. Since becoming a Christian I have asked God to forgive this lack of faith and appreciation. One solid pillar of my faith is that God did indeed protect me many times in the past. I try to make amends for my blindness every day by thanking him for watching over me then and now.

Remember the wonders he has done, his miracles, and the judgments he pronounced.

—Psalm 105:5

The Arctic Is Neutral

George Hurley, the young sailor-poet, wrote of his despair at the death that he witnessed:

No life boat for me, I die where I stand / Like an icicle, shiny and grand

The arctic is neutral, it takes no side / All dressed in white, waiting for its bride.

So much suffering, so many dying / So many shipmates died just for trying

All of their labor, all of the toil / all of the bodies covered with oil.

116

In combat I have experienced my own despair in the midst of violence and death. I was unfortunately not a Christian at that time. I anguished at the apparent randomness that took some and not others, and felt that God could not be involved in any of what I was seeing on a daily basis. I am not qualified even now to comment on God’s attitude toward war or those involved in the fighting. There have obviously been good men and women on all sides in every war praying fervently for deliverance. Many believe that their prayers were answered. What about those whose prayers were not answered?

There is no definitive answer to such a question. We don’t know the spiritual condition of those who have fallen, and we don’t know God’s plan for their eternal futures. We do know that everyone must die eventually and that the span of our lives, whether twenty-five years or eighty-five, is nothing from God’s perspective. God never promised to shield us from hardship or harm. He only promises to be with us in every situation, if we faithfully turn to him. We also have the same dilemma as the apostle Paul, not knowing who gets the better deal: the person called to heaven or the person left to face the challenges of this world.

For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain… I am torn between the two: I desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far; but it is more necessary for you that I remain in the body.

—Philippians 1:21, 23 24

The Best Solvent

An unknown sailor was concerned that so many of his friends were wasting time worrying. He wrote an article that appeared in his ship’s weekly newsletter in June 1942 with timely advice for any era:

Have you ever stopped to realize that the best solvent for worry is work? Throw yourself into your job, master its details and in addition to serving your ship and country better, you will be rewarded by contentment.

Work is healthy! You can hardly put more on a man than he can bear. But worry is rust upon the blade. It is not movement that destroys the machinery, but friction… many deaths are provoked chiefly by worry over matters which never repay the time wasted on them, and which breed a race of brooders prone to disease and death…

Be matter of fact: first get to the bridge, then cross it.

And meanwhile, don’t worry whether you get to the bridge or not.

What does your anxiety do? It does not empty tomorrow of its sorrow; but it does empty today of its strength.

117

Jesus proclaimed the same message during his Sermon on the Mount. He asked, “Who of you by worrying can add a single hour to his life?” (Matthew 6:27; Luke 12:25). The point is clear: worrying accomplishes nothing. It is a pointless mental activity that only distracts us from what we should be doing. With Jesus in our lives we can focus on the truly important things that can actually be accomplished, while lifting those other concerns to him.

But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself.

—Matthew 6:33–34

An Act of Faith

Steaming in convoy at night was an exhausting experience in seamanship. To reduce the risk of submarine attack every ship had to make sure that no lights were showing. This made keeping station with the rest of the convoy an unremitting task of intense focus and eyestrain. If an escort ship were to lose position there was more than embarrassment involved. A dangerous gap could open in the defensive screen around the convoy that could let a submarine through. As if this was not challenging enough, the escorts often were required to follow a zigzag course to further thwart submarine attacks. In his classic,

The Cruel Sea, Nicholas Monsarrat describes one young corvette officer’s experience with this maneuver:

A zigzag on a pitch-black night, with thirty ships in close contact adding the risk of collision to the difficulty of hanging on to the convoy, was something more than a few lines in a Fleet Order. Lockhart… evolved his own method. He took Compass Rose out obliquely from the convoy, for a set number of minutes: very soon, of course, he could not see the other ships, and might have had the whole Atlantic to himself, but that was part of the manoeuvre. Then he turned, and ran back the same number of minutes on the corresponding course inwards: at the end, he should be in touch with the convoy again, and in the same relative position.

It was an act of faith that continued to justify itself, but it was sometimes a little hard on the nerves.

118

We live our lives with faith that the things we rely on every day will continue to work properly: a shipboard procedure, the automobile brakes, our relationships. Such faith is a matter of trust based on experience. The most vital part of our lives is of course our relationship with God, which we have entirely through faith. This faith is also based on experience and grows as we actively practice it. The more we seek him by praying and listening, the more we will feel his presence and grow in confidence that we are “on station,” even in the darkest and most uncertain waters.

Now faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see.

—Hebrews 11:1

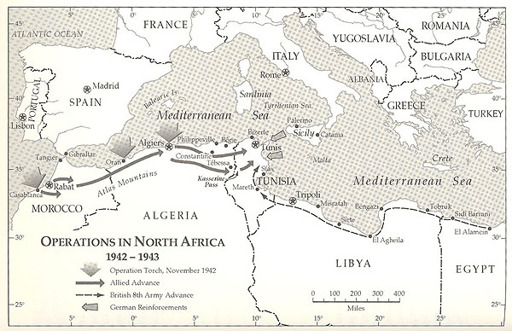

War in the Desert

The shipping lanes of the Mediterranean Sea have historically been vital to France and England in support of their commerce with the Middle East and Asia. In 1939, even though war was imminent in Europe, the Mediterranean seemed secure, with strong British and French naval and ground forces in place and an ostensibly neutral Italy. This picture changed dramatically with the defeat of France. On June 10, 1940, the day after the fall of Paris, Italy declared war on the Allies. With an Italian army and navy opposing them and a French fleet potentially in enemy hands, Britain suddenly faced a crisis on another front.

With visions of a new Roman Empire, Mussolini ordered his forces in Libya to begin a land offensive on September 13 to seize Egypt and the Suez Canal. Marshal Graziani, with two hundred fifty thousand troops available in Libya, ordered the Italian 10th Army to advance into Egypt. They were opposed by thirty thousand British, Indian, and Australian troops under Gen. Archibald Wavell. After advancing about one hundred kilometers, the Italian advance was stopped at Sidi Barrani and was then routed by a counterattack that advanced five hundred miles back into Libya.

To shore up his faltering ally, Hitler deployed Luftwaffe units to Italy in December 1940 to interdict British shipping and to keep supply lines open to North Africa. The Afrika Korps was organized under Gen. Erwin Rommel and began moving to Africa in early 1941. It consisted initially of one light division and one panzer division, and was later expanded into the Panzer Army Africa. Rommel soon earned the nickname, “Desert Fox,” and began to make his presence felt.

Disregarding instructions from Italian authorities and his own superiors, the German general quickly launched an offensive that penetrated almost to Egypt. He finally had to stop in late May to resupply and reorganize his forces. From this point on, for over a year, the war in North Africa became a back-and-forth struggle along a narrow one-thousand-mile strip of Libyan and Egyptian coastline. Each side sought to build up strength for the next offensive while seeking some way to outflank or outguess the enemy.