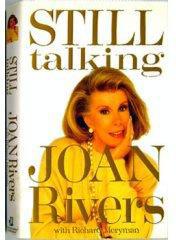

Still Talking

Authors: Joan Rivers,Richard Meryman

STILL TALKING

BY

JOAN RIVERS

WITH RICHARD MERYMAN

AVON BOOKS

A division of

The Hearst Corporation

New York, New York 10019

Copyright ţ 1991 by Joan Rivers

Front cover photograph by Charles William Bush Published by arrangement with’tLrtle Bay Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-53477 ISBN: 0-380-71992-4

First Avon Books Printing: December 1992

AVON TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND IN OTHER COUNTRIES, MARCA REGISTRADA, HECHO EN U.S.A.

Printed in the U.S.A.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Melissa,

who has shared so much of the pain,

and so little of the glory

Thanks to Susan Kamil,

who was head of the cheerleading team,

and to Dorothy Melvin and Tom Pileggi,

who taught her the steps.

1

THE news had already been on the radio, and all hell had broken loose. The phones had been ringing with calls from friends and the press, but my daughter, Melissa, had already taken over. It was she who received the phone call from Philadelphia, and immediately called the house staff together. Her face streaming with tears, she told them, “I want you to know he loved you all very dearly.”

Now she was making the important calls to the extended family and organizing the secretaries to notify a long list of friends and acquaintances. My assistant, Dorothy Melvin, had flown to Oklahoma to meet her boyfriend’s parents; at the airport they gave her the news, and she took the next plane back.

Flowers began arriving-which pleased and enraged me for my husband’s sake.

The time when Edgar needed such attention was after the firing from Fox.

They were two months late. I sent most of them to an AIDS hospice.

The awful practicalities took over-can Edgar be cremated in time for a service on Sunday? Which temple for the funeral? Who should speak at the service? Who should handle the catering for the reception afterward? How many valet parkers would we need? I think everybody during the first days of a death feels the person is somehow there, knows what is happening, and the buzzwords for the next three days were, “It should be done right. Edgar would have wanted that. “

A rabbi arrived with words but no comfort. The press was telephoning. My publicist, Richard Grant, came to write the press release and work up an obituary. Almost

1

nobody knew that I had separated from Edgar, and I was terrified that it would leak out and become a scandal, the press picking us apart again.

During this frenetic activity, my Yorkshire terrier, Spike, came into the office and did something he had never done before, never did again. He jumped up on Edgar’s chair and onto his desk and sat there.

Throughout the day my support group kept arriving. Coral Browne, wife of Vincent Price, heard the news on the radio, and this elegant British actress, never out of her Chanel suit, jumped into her car wearing a bathrobe and slippers and drove over immediately. She was furious with Edgar for doing this to me, but insisted: “All right, darling, you’ve got to deal with this. You’ll get through it.”

From New York came Tommy Corcoran, a loyal friend since before Edgar; from Las Vegas came Mark Tan, a columnist who adored Edgar, their friendship dating back to the nights we roamed the casino showrooms. My dear friend and dresser Ann Pierce came from Vegas and moved in. Dorothy Melvin moved in. Kenneth Battelle, the great hairdresser, who had been wonderful to me for twenty years, called and said, “What can I do?” I said, “Come out. “

This man who in thirty-four years of business had never missed or broken an appointment, this Calvinist who once worked right through pneumonia, got on the next plane.

Tom Pileggi, though Edgar’s closest friend, did not come out, and I completely understood. When Edgar lied to him about his state of mind, saying, “I won’t do anything foolish,” Tom answered, half joking, “If you do, I won’t come to your funeral. ” Well, Tom lived by the code that a man’s word is his bond. That weekend, full of anger and sorrow, he went off by himself on his boat.

When Roddy McDowall arrived, very consoling, a man who truly loved Edgar, he brought a message from Elizabeth Taylor. She had told him, “If Joan wants to call me, she can.” I thought, Call her? Who the hell does she think she is? Gee, if I’m real polite maybe she’ll even say something kind to me. That anger was the first emotion to penetrate my numbness.

STILL TALKING 3

In my trancelike state, I wanted people around me who were feeling the sharp pain of mourning, who could do my feeling for me, could give Edgar that testimony to his value. I wanted Edgar, who had been so unloved for the last three years, so put down and hurt and publicly humiliated, to have their caring and respect. The only people I wanted around were those who knew the worth of the man. Certain relatives, who would have upset him, we asked not to come.

My inner circle constantly gathered in little groups, talking, talking, talking, often in the kitchen when they came down to get a snack, or in strange places-meeting each other on the stairs and sitting down and talkingsearching, searching for the why, searching for the unknowable.

Billy Sammeth, my manager, said, “He had played out all his cards. ” I repeated to the others something Edgar said to Tom Pileggi-“Pride can kill a man, and that’s all I have left.” Most of those closest to me in my life believed that Edgar wanted to be found and have his stomach pumped. They argued that he had left his hotel room door unlocked-very un-Edgar-so security guards could easily save him. They pointed out that his body was found on the floor, evidence that he had reached too late for the telephone and missed and fallen.

Melissa-and Tom Pileggi talking on the telephonebelieved that Edgar thought he had cancer, which ran in his family. They reminded us that he had a growth in his mouth that kept returning. Tom said, “He thought he was going to slowly deteriorate to nothing, and he didn’t want his family to see him die that way. ” For some reason, what gave me the most comfort, what I kept repeating, was somebody’s opinion that “Edgar was looking for a door to go through and take his pride with him.”

I guess I think that during all those days of mixed messages, he wanted in his head to die and in his heart to live. I think he was throwing out cries for help to bring me back, but people get enmeshed in their stratagems until they don’t know if attempting suicide is a game or feel, By God, I’ve got to do it. And then when Edgar felt the

pills taking over, it was, Uh-oh, this is stupid. I’ve got to get help.

One thing everybody agreed on, Edgar had needed to go into therapy. That would have been the only way to save him.

Throughout the morning Melissa was all poise and efficiency, directing the office. But as the day progressed, she began disintegrating, and the veil would momentarily drop and the pain was stark in her face.

I was dazed with shock. I could remember, as if it were a century ago, waiting in the hospital room that morning after minor surgery-and Melissa suddenly appearing, short of breath from running. She said, “Sit down. ” I said, “Tell me.” I like my bad news right away and standing up. She said, “Daddy’s dead.”

I have no memory of the next few minutes. I am told I went stark white. My right hand clamped onto the chair in front of me. Staring sightlessly out the window, I moaned over and over, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God. Oh, my God.”

In my head I screamed the words, “What have I done? What have I done?” If I had made that one phone call to Edgar saying, “Come home,” he would still be alive. I had killed Edgar as surely as though I had pulled a trigger.

I think the body takes over at crisis moments, knows what is best for itself, ignores the mind where the hysteria runs riot. I shut down, entered a strange sphere of detachment, floating above reality. I heard myself talking to people, but that was not me talking, that was my voice in an echo chamber.

The body also softens such a blow with disbelief. This had to be a mistake, a waking nightmare that would go away. I was waiting for somebody to call and say, “Wrong person. Terribly sorry. Gee, what an error.” I think that is what Melissa wanted from her mother, who had always taken care of everything-confirmation that nothing had happened, wanted me to say, “Oh, it’s all a mistake. Don’t bother yourself.”

She would find me-in the bedroom, the office, my

STILL TALKING 5

dressing room, the bathroom, the kitchen table late at night-and we would shut the door and talk and talk and talk, going over the same ground again and again. Sometimes I put my arms around her or held her hands. On that Friday, as we sat together on the small step up to my bathtub, she told me, “I can never be truly happy again. I’ll always be thinking, If only Daddy were here. He’s never going to see my children. He’s never going to meet the man I marry. “

She was devastated that her own father had lied to her, had said he was coming home. She flayed herself for not telephoning him a second time on Thursday night; maybe the sound of her voice would have changed his mind.

She looked for some rationale to ease her guilt. She said, “Nobody ever made a decision for my daddy, and we should allow him the dignity of making his own final decision.” Then she reminded herself that in Philadelphia he was not the rational man she admired and said, “He was my father, but he wasn’t my father. “

I tried to help her by interpreting Edgar, giving her reasons why he had been so terribly ill and frightened. We talked angrily about what the article in People magazine and Fox did to Daddy. I linked together for Melissa his disintegrating health, his Germanic background, his uprooted, displaced, isolated childhood, his belief that you always had to be what you were supposed to be and live up to that standard, his belief after Fox that the career was finished. I showed Melissa a little picture of Edgar on his first day of school in Germany, wearing a cap in the sun, the apple of his parents’ eyes, standing there still healthy, carrying a cone container of candy for the teacher. Ahead lay Hitler and TB and the heart attack and being tossed and turned and frustrated-and then his fulfillment was taken away, and again he was not allowed to have his dream.

But I was helpless to heal my daughter. To me motherhood had always been teaching and protecting, giving Melissa as much knowledge as I had about any situation that came up in her life. Though children totally reject advice, you hope you are planting a seed. When Melissa

was little, I would say, “Don’t waste your tears. God only gives you a certain amount, so don’t waste them on this.” Later when something bad happened-when her first romance broke up-I said, “Trust me. The pain will pass. ” My counsel had always been, “Whatever is bothering you, write it down in a book. Close the book, and a year later you’ll open it up and say, `Big deal.’ “

Now, those lessons were empty. This was what she had saved her tears for.

This would forever be a well of pain. I had no comfort to give Melissa, no way to protect her. For the first time as a mother, I felt helpless. There was no one I could call to make it okay, nothing I could do. I was now a failure as a mother as well as a failure as a wife. Instead of protecting my daughter, I had been the catalyst in the death of her father.

In the afternoon of that Friday my numbness gave way to anger-anger at myself, anger at Edgar for doing this to both of us, especially to Melissa, the one person for whom he felt unconditional love. In direct proportion to Melissa’s shift from shock into grief, my anger grew. I hated myself for giving in to it, for my weakness against it, for being so disloyal to this man who had loved me. I desperately wanted to dwell on my love, on our friendship, the way I felt I should.

I tried to tamp down the anger by seeking out people who had loved him. I tried to draw their mourning into myself to push away the rage, but then I would hate myself more because I felt I lacked the decency to grieve properly. I would see some sign of Edgar-his desk drawer slightly open and his pencil tossed on the top-and I would feel impaled by pain, and I would weep-then the sight of the pure despair on my daughter’s face would refuel my anger.

Late Friday afternoon, after my talk with Melissa in the bathroom, I sat by myself on the bathroom floor. My eyes went to the glass door of Edgar’s cabinet, the rows of pill bottles visible inside. Our life together had ended up in that cabinet. “You bastard!” I yelled out loud.

I wrenched open the door and swept every pill, shelf after shelf, into a big wastebasket, dropping them, spilling

STILL TALKING 7

them, flinging them, clumsy with rage. Then came the terrible tears of guilt. What kind of person was I? What kind of woman would drive a man to suicide and then strike out at him?