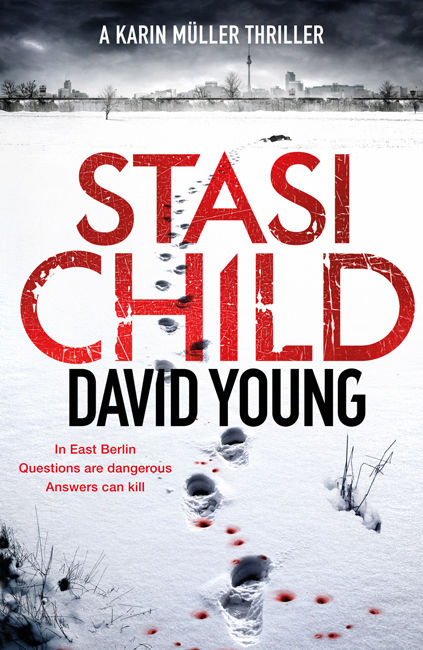

Stasi Child

Authors: David Young

STASI CHILD

DAVID YOUNG

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This novel is set in communist East Germany, the German Democratic Republic (in German the

Deutsche Demokratische Republik

, or DDR) in the mid-1970s, when the country had one of the highest standards of living of any in the Eastern bloc. At the time, with the Berlin Wall – or the Anti-Fascist Protection Barrier/Rampart as it was officially known in the East – firmly in place, few could have predicted the tumultuous events in 1989 which led to its dismantling.

The DDR has come to be identified with its feared Ministry for State Security, the

MfS

, more commonly known as the Stasi. But while the existence of the Stasi – and its network of unofficial informers – was known about at the time, its apparently bizarre methods and the huge number of people who worked for it only fully came to light

after

1989.

Criminal investigations were generally the preserve of the People’s Police (

Volkspolizei

or

VOPO

for short) and in particular its CID division (the

Kriminalpolizei

or

Kripo

). If a case had significant political overtones, then it would be taken over by the Stasi, which had its own criminal investigation department, its own forensic teams and so forth. Cases where the Stasi and

Kripo

worked together on the same team – such as the fictional one that follows – were rare, although there would often be liaison at a high level. However, many members of the

Kripo

were, of course, Stasi informers. And the People’s Police was as much an organ of the state as the Stasi: its remand prison at its Keibelstrasse headquarters near Alexanderplatz in Berlin as equally hated as those of the Stasi at, for example, Hohenschönhausen.

A possible confusion for English-language readers is the police and Stasi ranking system, based on that of the army. A murder commission or squad – such as the fictional one here – would generally be led by a captain (

Hauptmann

– the equivalent of the UK’s detective chief inspector), or perhaps – as in this case – a first lieutenant (

Oberleutnant

). This rank, that of my character Karin Müller, should not be confused with the much more senior lieutenant colonel (

Oberstleutnant

), one rank below colonel (

Oberst

).

For the sake of authenticity, I’ve retained the German ranks, and also the often monotonous communist use of Comrade (

Genosse/Genossin

) when addressing colleagues, particularly in the presence of senior officers.

D.Y.

1

February 1975. Day One.

Prenzlauer Berg, East Berlin.

The harsh jangle of a telephone jolted

Oberleutnant

Karin Müller awake. She reached to her side of the bed to answer it, but grasped empty space. Pain hammered in her head. The ringing continued and she lifted her head off the pillow. The room spun, she swallowed bile and the shape under the blankets next to her reached for the handset on the opposite side of the bed.

‘Tilsner!’ The voice of her deputy,

Unterleutnant

Werner Tilsner, barked into the handset and rang in her ears.

Scheisse! What’s he doing here?

She began to take in her surroundings as Tilsner continued to talk into the phone, his words not really registering. The objects in the apartment were wrong. The double bed she was lying in was different. The bed linen certainly didn’t belong to her and her husband, Gottfried. Everything was more . . . luxurious, expensive. On the dresser, she saw photographs of Tilsner . . . his wife Koletta . . . their two kids – a teenage boy and a younger girl – at some campsite, smiling for the camera on their happy-family summer holidays. Oh my God! Where was his wife? She could be coming back at any moment. Then she started to remember: Tilsner had said Koletta had taken the children to their grandmother’s for the weekend. The same Tilsner who was constructing some tall tale at this very moment to whoever was on the other end of the phone.

‘I don’t know where she is. I haven’t seen her since yesterday evening at the office.’ His lie was delivered with a calmness that Müller certainly didn’t share. ‘I will try to get hold of her and, once I do, we will be at the scene as soon as possible, Comrade

Oberst

. St Elisabeth cemetery in Ackerstrasse? Yes, I understand.’

Müller clutched her pounding forehead, and tried to avoid Tilsner’s eyes as he replaced the handset and started to get out of bed, heading for the bathroom. She wriggled about under the covers. It had been cold last night. Freezing cold. She’d kept all her clothes on, and her underwear now chafed at her skin under the tightness of her skirt. Before that, Blue Strangler vodka. Too much of it. Her and Tilsner matching each other shot for shot in a bar in Dircksenstrasse; a stupid game that seemed to have ended up with them in his marital bed. She could still taste the remains of the alcohol in her mouth now. She wasn’t entirely sure what had happened after the bar, but just the fact that she’d spent the night at Tilsner’s was something she knew she could never let Gottfried discover.

Tilsner was back now, proffering a glass of water with some sort of pill fizzing inside.

‘Drink this.’ Müller drew her head back slightly, grimacing at the concoction and its snake-like hiss. ‘It’s only aspirin. I’ll make some coffee while you tidy yourself up.’ The smirk on his unshaven, square-jawed face spoke of insolence, disrespect – but it was her own fault for letting herself get into this situation. She was the only female head of a murder squad in the whole country. She couldn’t have people calling her a whore.

‘Hadn’t we better get straight there?’ she shouted through to the kitchen. ‘It sounded urgent.’ The words reverberated in her head, each one a hammer blow.

‘It is,’ Tilsner shouted back. ‘The body of a girl. In a cemetery. Near the Wall.’

Müller downed the aspirin and water in one long swallow, forcing herself not to retch it back.

‘We’d better get going immediately, then,’ she shouted, her voice echoing through the old apartment’s high-ceilinged rooms.

‘We’ve time for coffee,’ Tilsner replied from the kitchen, clanging cups and pans about as though it was an unfamiliar environment. It probably was, except on International Women’s Day. ‘After all, I’ve told

Oberst

Reiniger I don’t know where you are. And the Stasi people are already there.’

‘The Stasi?’ questioned Müller. She’d moved in a slow trudge to the bathroom, and now studied her reflection with horror. Yesterday’s mascara smudged around bloodshot blue eyes. Rubbing her fingers across her cheeks, she tried to stretch away the puffiness, and then fiddled with her blonde, shoulder-length hair. The only female head of a murder squad in the whole Republic, and not yet in her thirtieth year. She didn’t look so baby-faced today. She breathed in deeply, hoping the crisp morning air of the old apartment would quell her nausea.

Müller knew she had to clear her head. Take control of the situation. ‘If the body’s next to the anti-fascist barrier, isn’t that the responsibility of the border guards?’ Despite the reverberations through her skull, she was still bellowing out the words so Tilsner could hear down the corridor. ‘Why are the Stasi involved? And why are we –’ Her voice tailed off as she looked up in the mirror and saw his reflection. Tilsner was standing directly behind her, two mugs of steaming coffee in his hands. He shrugged and raised his eyebrows.

‘Is this a quiz? All I know is that Reiniger wants us to report to the senior Stasi officer at the scene.’

She watched him studying her as she pulled Koletta’s hairbrush through her tangled locks.

‘You’d better let me clean that brush after you’ve used it,’ he said. Müller met his eyes: blue like hers, although his seemed remarkably bright for someone who’d downed so much vodka the night before. He was smirking again. ‘My wife’s a brunette.’

‘Piss off, Werner,’ Müller spat at his reflection, as she started to remove the old mascara with one of Koletta’s make-up pads. ‘Nothing happened.’

‘You’re sure of that, are you? That’s not quite how I recollect it.’

‘Nothing happened. You know that and I know that. Let’s keep it that way.’

His grin was almost a leer, and she forced herself to remember through the hangover muddle. Müller reddened, but tried to convince herself she was right. After all, she’d kept her clothes on, and her skirt was tight enough to deny unwanted access. She turned, snatched the coffee from his hand and took two long gulps as the steam rising from the beverage misted up the freezing bathroom mirror. Tilsner reached around her, grabbed the mascara-caked pad and hid it away in his pocket. Then he picked up the brush and started removing blonde hairs with a comb. Müller rolled her eyes. The bastard was clearly practised at this.

They avoided looking at each other as they descended the stairs, past the peeling paint of the lobby, and walked out of the apartment block into the winter morning. Müller spotted their unmarked Wartburg on the opposite side of the street. It brought back memories of the previous night, and his insistence that they return to his place for a sobering-up coffee – Tilsner seemingly unconcerned about his drink-driving. She rubbed her chin, remembering in a sudden flash his stubble grazing against it like sandpaper as their lips had locked. What exactly

had

happened after that?

They got into the car, with Tilsner in the driver’s seat. He turned the ignition key, his expensive-looking watch shining in the weak daylight. She frowned, thinking back to the luxurious fittings in the apartment, and looked at Tilsner curiously. How had he afforded those on a junior lieutenant’s salary?

The Wartburg spluttered into life. Müller’s memory was slowly coming back to her. It had only been a kiss, hadn’t it? She risked a quick look to her left as Tilsner crunched the car into gear, but he stared straight ahead, grim-faced. She’d need to think up a very good excuse to tell Gottfried. He was used to her working late, but an all-nighter without warning?

The car’s wheels spun and skidded on the week-old snow that no one had bothered to clear. Overhead, leaden grey skies were the harbinger of more bad weather. Müller reached out of the car window and attached the flashing blue light to the Wartburg’s roof, turning on the accompanying strangled-cat siren, as they headed the few kilometres between Prenzlauer Berg and the cemetery in Mitte.