Stars of David (48 page)

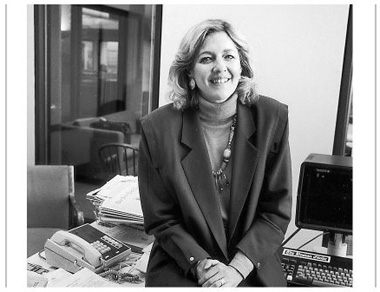

Ellen Goodman

ELLEN GOODMAN PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1987 BY JILL KREMENTZ

BOSTON GLOBE

COLUMNIST ELLEN GOODMAN, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1980 for distinguished commentary and whose column is syndicated to over 450 American newspapers, says her thick blond hair used to tag her as gentile, especially in the dating scene at Radcliffe. “It was more of an issue that nobody knew that I was Jewish; I had a neutral nameâHoltzâand that blond hair. Coincidentally, I was paired with a roommate who was Jewish. She introduced me to artichokes.”

How Jewish does she feel now? “It's sort of like when someone says, âAre you a feminist?' and they think you should duck under the table. But my answer to âAre you a feminist?' is âSure; I'm part of a hundreds-of-years-old tradition of women who believe in equality.' If someone says, âAre you Jewish?' that's also a question rarely asked by someone who is thinking positively. Particularly when we were kids. I remember, when I was in sixth or seventh grade, being pushed on the way home from the swimming poolââThe Tank,' as we called itâby some Irish girls. I don't remember whether I told my parents or not.”

Does she recall being frightened? “The thing that I've never been quite sure of is why I didn't run away. I guess it was an issue of twelve-year-old dignity.”

Goodman is eating a chicken pita sandwich at a round wooden table in her quiet second-floor office close to Harvard Square. She says she was raised by a German-Jewish father, an attorney, who became more involved in Jewish life as an adult. “He developed what I would describe as a âthey'regoing-to-kill-you-for-it-anyway-so-you-better-know-something-about-it' attitude,” says Goodman. “The weirdest part of his Jewish activity was that in 1948 or 1949, he became National Commander of the Jewish War Veterans. (He was in the army but never went overseas.) He thought there should be a Jewish military group for the image of the Jews.”

Her father worked on John F. Kennedy's campaign for the U.S. Senate in 1952. “My Uncle Mike referred to my father as âVice President in Charge of the Jews.' He and Kennedy became quite close at that time; my parents went to [Jack and Jackie's] wedding. My mother describes herself as âthe only person who changed for the Kennedy wedding at a gas station in Rhode Island.' Everyone else who went to the wedding was rather fancy.”

Goodman is very close to her daughter, Katie, who she says “bagged Hebrew school early on,” partly because Goodman didn't push it. “I think at some point I wanted that weekend time with her. I wasn't very committed and she wasn't all that interested. But we've always celebrated family Hanukkah, Passover, Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur.”

Katie married a man Goodman describes as a “Catholic-Baptist-Buddhist combo.” She's not sure how her grandson will be raised and won't say whether he had a bris. “I don't discuss my grandson's penis in print.”

Did she wish that Katie had married a Jew? “It's complicated. None of the children of the next generation in our family married Jews. In fact, I think the only one who will eventually have a Jewish life partner is my cousin, who's gay. His partner is converting to Judaism. In some ways I think he cares the most. But it was not important to me. However, it would have been important to me that she not marry someone who took

another

religion very seriously. For her to have married a very religious personâ or even an Orthodox Jewâwould have probably freaked me out.”

Goodman finishes her sandwich and, before I go, tries to sum up her view of Jewish identity. “When Madeleine Albright's linkage to Judaism came out, I remember thinking that her parents could have been self-hating, self-denying Jews; a lot of people had that reaction. But her parents could also have been people who didn't want to be defined by something they didn't believe in and so chose to convert or redefine themselves. Or they could have been totally secular people. So if you define them and her as Jewish, are you doing what the Nazis did, which is to make Judaism a race? If you don't, are you then denying a connection with an ancient tradition and group? If you insist on being connected to the past, what does it mean? I'm not being very articulate about this.

“Unless you are a true believer, should you maintain a connection based onâquote ââblood'? What do you think religion is? What do you think ethnicity is? It's endless. So a lot of people give it a good leaving alone. A lot of people deal with it as a serious part of their spiritual life and a lot of people leave it alone. I'm somewhere in that mush. Someone asked me once, âDo you pray?' And I said, âNo, I don't pray.' On the other hand, I've been on an occasional plane when I've given a little Shema. When the plane goes down, I may be saying a Shema.”

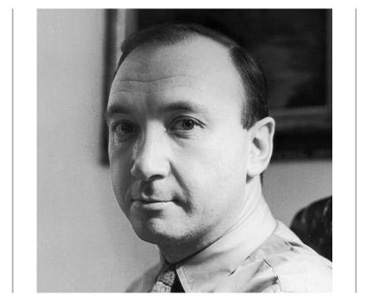

Jeff Zucker

WHEN JEFF ZUCKER, president of NBC Universal Television Group, who oversees NBC's news, cable, and entertainment, was struggling with colon cancer in 1996 at the age of thirty-one, he found himself reaching for faith. “I think we all use religion and God at convenient times, let's be honest,” he says in his large office in Rockefeller Center. “I think when I was sick, I definitely talked to God. I did do that. I probably talked to God in a way that I probably never did before or haven't enough since.”

Did it make him more religious? “I think a lot of people find comfort and solace in God or religion in times of trouble. And you don't have to be over-religious to want to ask somebody else for help. Whether you can see them or not. I think you always want to believe that there is a greater being.”

While Zucker was in treatment, he and his wife, Caryn, went to Temple Emanu-El to speak with the junior rabbi who married them. “I thought she was helpful,” he says. “She just gave us comfort.”

Recently he's been more drawn to Jewish ritual, spurred by fatherhood, not cancer: “It's been less about when I was sick and more about having children,” he says. “I do want my kids to have a sense of belonging to something they can hang on to and believe inâhaving a community. I think being Jewish is really that community.”

He says that view is shared by his wife, Caryn Nathanson, a former associate producer for

Saturday Night Live

. I ask if he thinks it's easier to be married to another Jew. “Totally. I think that if you grow up Jewish in Miami or New York or anywhere else, that there's a common thread of understanding and values that are implicit.”

Before he was married, was it important to him to find a Jewish wife? “I think I always knew that I would,” he replies, though he says he was more ecumenical in his dating years. “I think all Jewish guys like dating the shiksas,” he says with a smile. “But I don't want to insult you.”

Zucker grew up in Miami, where he was bar mitzvah and confirmed at Temple Israelâ“the most Reform synagogue in South Florida.” His family's weekly tradition was Hebrew school and football. “After Sunday school, my folks would pick me up and we'd go to the Dolphin game,” he recalls.

He said he didn't miss a Christmas tree, in part because Miami isn't exactly a winter wonderland that time of year, and he used to fast on Yom Kippur though he doesn't anymore. I ask him why not. “I don't know,” he answers. “Now that I have children, I would like to get back into doing it.”

He's currently a member of Temple Emanu-El in New York, and says his kids received an early dose of Jewish education in preschool at the 92nd Street Y. “Every Friday they would have prayers,” he explains. “So they know a little bit about Friday night Shabbat dinner. They know they're Jewish.”

How would he answer his children when they ask him what it means to be a Jew? The rapid-talking television executive pauses for the first time. “I think it means that we believe there's a God who looks out over all of us.” Another pause. “A large part of Judaism is the type of home you have and the feelings that are expressed there and the expectations that are around you. And it ties us to a tradition and a way of living that our grandparents and their grandparents lived.”

I wonder if, when he was sick, he made any bargains with God; especially after the cancer returned three years following the first bout. Zucker shakes his head. “No bargains. But you're always reaching out in times of need. And just because you can't see Him, doesn't mean He's not there.”

Neil Simon

NEIL SIMON PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1970 BY JILL KREMENTZ

MARVIN NEIL SIMON ONCE WROTE that he dropped his first name when he realized that “Marvin Simon” would never “be announced on the public address system at Yankee Stadium as playing center field for the injured Joe DiMaggio.” In a phone interview from Los Angeles, he says he did not grow up in “what you would call a really Jewish home.” His parents kept separate dishes for the High Holy Days and tore off pieces of toilet paper before the Sabbath arrived, so they wouldn't have to “work” on the day of rest. That was about the extent of it. “They ate the right food,” he adds.

Simon soured on religious education when he was chastised for asking what he thought was a reasonable question in Hebrew school. “The rabbi was telling us about Adam and Eve and their children, Cain and Abel,” Simon recalls. “He said Cain slew Abel and then went out into the world and wherever he went, people shunned him. And I said, âWhat

people

? You just told us they were the only human beings on earth.' The rabbi said, âShut up.'” Simon pauses. “Things like that are what discourage you from having a religious background.”

He also disliked that the subject Hebrew school seemed to care most about was tuition. “The rabbi would say to me, âYou got the money? Did you give us the money yet?' It's very possible and probable that the place I went to in Washington Heights was not a very good place of learning.”

Simon also found observance too demanding. “I think one of the things that put me off a little bit was the amount of time you had to spend to be a good Jew,” he says. “The amount of times you had to go to synagogue.” His older brother, Danny, went more often. “He had more fear of it,” Simon recalls. “My brother would sleep next to me and I remember hearing him at night praying, âPlease, Jewish God, give me this; please, God, give me that.' I thought it was interesting because I said, âLook; he's making selections.'”

In Simon's memoir,

Rewrites

, he recounts the family's annual visit to shul on the High Holy Days and how his father insisted he recite the prayers in Hebrew. “I would say, âI don't know what the Hebrew means.' He answered, âDo what I say. God doesn't understand English.'”

Simon, seventy-seven when we speak, says the anti-Semitism he saw in his Bronx neighborhoodâ“there were always street fights”âpaled by contrast to his later stint in the army. “In the army, I knew that I was Jewish because they would tell me so,” he says. “That was when I really got it. It struck me as being so hypocritical and kind of stupid that the guys who were the cooksâwho were to me the dumbest group of all the guys that I metâwere putting us all down for being Jewish.”

In

Biloxi Blues

, the third of Simon's autobiographical trilogy about a Brooklyn Jewish family, the main character, Eugene Jerome (played on Broadway by Matthew Broderick), goes to boot camp and learns that the same American soldiers who are champing at the bit to kill Nazis also happen to hate Jews. When the character Joseph Wykowski ridicules Eugene's fellow private, Arnold Epstein, Eugene does nothing. “I never liked Wykowski much and I didn't like him any better after tonight,” Eugene confides to the audience. “But the one I hated most was myself because I didn't stand up for Epstein, a fellow Jew.”

This Pulitzer Prizeâwinning playwrightâwith more than thirty plays and twenty films to his credit, including

Barefoot in the Park, The Odd Couple, The Sunshine Boys, The Goodbye Girl

, and

Brighton Beach Memoirs

â chose to re-create one of his first comedy-writing jobs in his script for

Laughter on the 23rd Floor

. It was based on the writing team of Sid Caesar's

Your Show of Shows

, which included Simon, Carl Reiner, Larry Gelbart (who later created M*A*S*H), Mel Brooks, and Caesar himself. “Almost all of them were Jewish,” he says. “It was just familiar and it made things easier. There would be things that were very funny that were said in the room that would come from a place familiar to us all. If a guy came from Ohio, it would be hard for him to catch up.”

He sounds annoyed when I ask him if he thinks American humor has been shaped in large part by Jewish humor because so many comedians are Jewish. “I have such a hard time talking about this and my answers are always the same,” Simon replies. “Even having difficulty talking about it says something about what my background was like.”

But Simon has often been described as a Jewish playwright. “I always felt that people were trying to pinpoint clues and say, âIs this a Jewish play?' and I never thought of that. Even though I thought my characters were sometimes probably Jewish.

Barefoot

wasn't Jewish.

Come Blow Your Horn

was.” I ask if he's bothered when critics or commentators analyze the Jewishness of his work. “It only bothers me in that not all the plays are about that,” Simon answers.

He also resists speaking about his personal life. It's well known that he was deeply distraught when his first wife, Joan Baim, died of cancer in 1973 after almost twenty years of marriage, leaving their two daughters, Nancy and Ellen. In his memoir, he writes about his helplessness watching his wife slip away.

“I looked for the God I hoped existed but was too cynical to believe in.

It did not, however, stop me from asking Him to point me in the right direction, as

I mumbled silent prayers on the carpet of my office in the late-night hours when Joan

was asleep.”

When I ask him whether his daughters feel Jewish, he says, “The youngest oneâwho's now fortyâstarted to look into it for herself in college and went to synagogue for a long time to see what she could get out of it. She wouldn't talk to me about it much; she just felt that maybe she'd missed something.”

I can tell that Simon is ready to get off the phone. When I ask my last questionâhow much it matters to him to be JewishâI assume he'll brush me off; but his answer surprises me. “It matters to me like my hands matter to me,” Simon replies. “It's there.”