Starcross (6 page)

Authors: Philip Reeve

Still smiling, Mother turned to look out through the crystal windows at the promenade, and at the bone-dry, bone-white sandscape stretching away towards that hard horizon. A fitful breeze was blowing dust devils between the wheels of the bathing

machines which waited mournfully in the starlight at the desert’s edge. All else was as dry and still and silent as the land of Death.

‘How long has the tide been out?’ she asked.

‘About one hundred million years.’

‘And when does it come back in?’

‘Oh, every twelve hours or so.’

‘How

very

intriguing,’ said Mother.

In Which I Have a Curious Encounter, and a Light Breakfast.

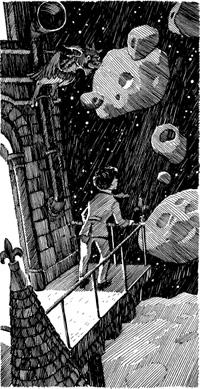

Our suite of rooms was at the very top of one of Starcross’s airy turrets. One reached it by climbing a long spiral of stairs, a perfect cataract of blood-red carpet, barred with gilt stair-rods. You would hardly believe the view which we had from our sitting room! I flung wide the windows and stepped out on to the wrought-iron balcony outside, gazing up in wonder at a sky

full of tumbling asteroids. ‘Look,’ I cried. ‘There is Vesta! And there is New Westmoreland, and Winnet, and the celebrated Ferrous Dumpling …’

But Mother and Myrtle only yawned, and declared that they wished to take a restorative nap before we all went down to breakfast.

There was a bedroom for each of us: the neatest, cleanest rooms you can imagine, each with a closet and a washstand and a brass bedstead. Myrtle and Mother retired to theirs, and I lay down in mine, but I could not sleep. I wanted to be up and

doing

, not wasting the first hours of my holiday in dull slumber! Oh, I put out the light and

tried

to sleep, but

sleep would not come. I was aware of the distant humming of gravity generators deep in the hotel somewhere, and the gleam of asteroid light through the crack of my bedroom door. And I was aware, too, of a strange feeling that I needed to

open

that door and look out into our sitting room.

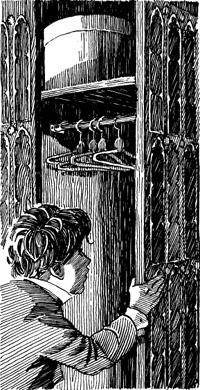

After a while I lit the lamp again, and gave into temptation. I eased the door open gently, for I could tell by the quality of the silence that Myrtle and Mother had both fallen asleep. The sitting room lay in darkness, except for the faint pale oblongs of the starlit French windows, and the lace curtains, which stirred like ghosts in a gentle breeze.

Cautious and expectant, I crossed the soft carpet and opened a closet. I had not noticed this closet earlier, yet now I somehow knew that it was there, and

that I should find something intriguing inside it.

At first there seemed to be nothing inside but a dangle of wooden coat hangers, which I took care not to rattle, as I was afraid it would wake Mother and Myrtle. Then, on a shelf above me, I noticed a large hatbox. I lifted it down. It was made of stiff white card, and printed on the lid was this legend:

TITFER’S TOP-NOTCH TOPPERS

Taking the box into the glow of lamplight from my halfopen bedroom door, I set it down on an occasional table, where I took off the lid. Inside, nestling in a lot of crisp crêpe paper, sat the tallest, blackest silk top hat I had ever seen. Even the lining was black, and without any label to say who had made it; but it did not need one, for I knew that Mr Titfer was the finest hatter in the Solar System, and a hat as splendid as this could only have been created by him.

10

I remember wondering what previous guest had left it behind in my closet, and why he had thought fit to bring such formal headgear to a beach resort.

And then, naturally, I felt an urge to put the hat on. But as I pushed aside the crinkling paper and made to lift it from its box a voice behind me whispered softly, ‘Moob!’

I looked up, startled, the hat forgotten. ‘Myrtle?’ I breathed. But Myrtle was asleep; I could hear her maidenly snores through her bedroom door, and anyway, she is not the sort of girl who goes around saying ‘Moob!’ in the middle of the night.

‘Moob?’ came the voice again, sounding plaintive. Perhaps it was not a voice at all, I reasoned, but only the wind moaning around our turret. I went to the window, and found that I had left it ajar – that was why the curtains had been billowing in such a ghostly manner. I made to close it, then, on a sudden impulse, opened it wider instead and stepped out to stand upon the balcony once more. The air of Starcross was thin, and smelled like string.

‘Moob!’ whispered the voice, or the wind, or whatever it was. A shadow moved at the far end of the balcony and I almost yelped with fright. Then, telling myself not to be so funky, I edged towards the place. That part of the balcony was deeply shaded by the space ivy growing up the turret wall. Was it my imagining, or did two pale flames burn in the darkness there, no larger than the flames of safety matches,

yet steady, and set side by side, for all the world like watchful eyes?

A cat, I thought, with some relief, and said, ‘Here, puss, puss, puss …’

Suddenly I felt an odd lurching sensation and a wave of dizziness which made me snatch at the balcony rail for support. When it passed, the balcony was bathed in light. My own startled shadow was thrown against the wall, and another shadow,

a shadow cast by nothing that I could see

, slid like an oiled black eel between the railings of the balustrade.

I turned to search for it, and stopped, amazed. The inky sky with its scattering of asteroids was changed to a spotless dome of azure blue. Mid-morning sunlight filled it and shimmered on the waters of a bay which lay where, only seconds before, there had been nothing but a waterless sea of sand. The knoll was an island now, and the air was full of the invigorating scent of ozone. I could

hear the crisp sigh and snore of the little waves as they curled in to break upon the shore, and see a troop of burnished automata emerging from the hotel’s side entrance to pull down the awnings of the beach cafe, rake the sand and untether the bathing machines.

I do not know how long I stood there, dumbstruck, gawping at that sudden ocean. I did not move until I heard the cheerful clamour of a gong, announcing that it was time for breakfast.

In the breakfast room, just as Mr Titfer had promised, we met some of our fellow guests: a large, flowery-looking lady, who beamed most cheerfully at us as we entered, and elbowed her small, meek husband so that he looked up from his scrambled egg and beamed too, and an elderly gentleman with a military air, who sat alone at a window-table, dividing his toast into neat triangles and applying butter and marmalade with brisk strokes of his knife.

Automated waiters saw us to our table and inquired in their flat voices whether we should like tea or coffee, brown toast or white?

‘Why, tea, of course,’ cried Myrtle, startled and mildly scandalised. ‘We are English! And who on earth would want brown toast? White, with marmalade, if you please.’

The waiter executed a mechanical bow and went scudding silently off on well-oiled casters to fetch our breakfasts. As he left, my mother caught the eye of the military-looking gent, who seemed amused by Myrtle’s outburst.

‘We must tell Titfer to see if he can’t make those clockwork men of his able to distinguish English guests from those from those of other nations, eh?’ he chuckled. ‘Pray permit me to introduce myself. I am Colonel Harry Quivering of Her Majesty’s Martian Army (Ret’d).’

‘Mrs Emily Mumby,’ said my mother sweetly. ‘And these are my children, Myrtle and Art.’

The colonel said that he was pleased to meet us, and that in his opinion it would liven the place up a bit to have some kids about. (You may imagine how this went down with Myrtle.) He went on to explain that he had been several weeks at Starcross. It was, he claimed, the best-appointed

billet he had ever kipped in, and he had lived in his time everywhere from London to the wilds of Mercury. ‘Titfer certainly knows his business,’ he concluded.

‘Indeed. I must say we are very impressed by the sea view,’ said Mother, gazing out thoughtfully at the glittering blue expanse beyond the promenade. ‘How does he do it, do you think?’

‘I’m afraid I couldn’t venture to say, ma’am,’ said the colonel, spearing a kipper with the practised ease of one who has spent many years cactus-sticking in the badlands of Mars. ‘Some sort of scientific miracle, I daresay. Science is advancing with such great leaps in the present age that it’s impossible for an old soldier to keep up with it. One never knows what these brainy coves like Titfer will come up with next!’