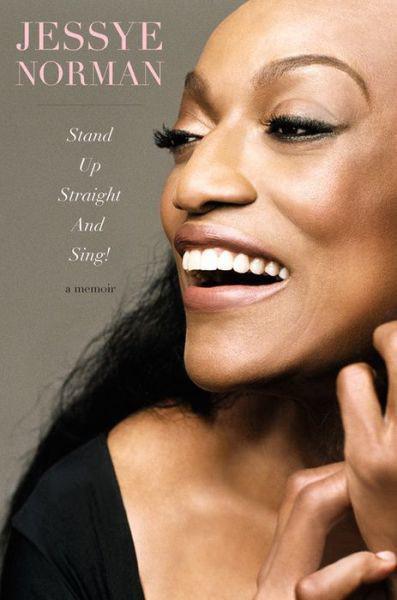

Stand Up Straight and Sing!

Read Stand Up Straight and Sing! Online

Authors: Jessye Norman

Tags: #Singer, #Opera, #Personal Memoirs, #Music, #Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography, #Retail, #Composers & Musicians

Table of Contents

Church, Spirituals, and Spirit

Racism as It Lives and Breathes

The Song, the Craft, the Spirit, and the Joy!

Copyright © 2014 by Jessye Norman

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Norman, Jessye.

Stand up straight and sing! / Jessye Norman.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN

978-0-544-00340-8

1. Norman, Jessye. 2. Sopranos (Singers)—United States—Biography. I. Title.

ML420.N736A3 2014

782.1092—dc23

[B]

2013046581

e

ISBN

978-0-544-00338-5

v1.0514

All song translations © Jessye Norman.

Do not reproduce without permission of author.

I am honored to dedicate this book first to my parents, Janie and Silas Norman Sr., then to my siblings, Elaine, Silas Jr., Howard, and our beloved angel, George.

And lastly to our big, bountiful family, with every single one of whom our ancestry is shared, as well as those who compose an extended, multitudinous group. As Richard Bach wrote:

“The bond that links your true family is not one of blood, but of respect and joy in each other’s life.”

Blest be the tie that binds.

Introduction

In the summer of 1972, at the first rehearsal of what became a thrilling concert performance of

Aida

with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl, I met a young soprano who was making her American operatic debut and about whom I had heard much—but whose voice I had not heard at all. Friends who had had told me, “Just wait!” Fortunately I did not have to wait long; nor did I have to wait to discover that this brilliant young woman was well on her way to a fully realized career as one of the very rare sovereign artists.

Over the more than forty years since that day I have had the joy and privilege of making music with my friend, Jessye Norman. Indeed, we have evolved a simple and all-but-tacit language in our collaborative process so that we are able to react to one another instantly on stage. She is an extraordinarily dedicated artist, extremely disciplined, but at the same time deeply expressive, lively, and spontaneous in response to every detail demanded by the composer of whatever music is at hand. Our work has encompassed an especially diverse repertoire for voice and instruments—opera, oratorio, and

songs

!—dozens of small masterpieces of words and music for voice and piano; perhaps the most astonishing repertoire of all. Not every great composer wrote operas or oratorios but they all wrote songs—

glorious

songs: Beethoven, Schubert, Strauss, Mahler, Wagner, Brahms, Ravel, Debussy, Poulenc, Berg, Schumann, Schoenberg, Wolf, Ives, Copland, to name a few, and of course, “Anonymous,” the most prolific of all, over many centuries, an incredibly vast collection of the world’s folksongs and spirituals.

All of these composers provided us with far too many memorable collaborations to describe in this short introduction. That may have to wait for my memoir! But the shortest possible list of my favorites would have to include:

- Our first “Recital with Orchestra” with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, in which Jessye sang the entire program, just as she would in a recital with piano.

- Beethoven’s

Missa Solemnis

with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival. - Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festival on the occasion of Jessye’s Salzburg debut.

- Her performing as soloist in the first of what became an ongoing series of concerts with the Met Orchestra playing as a symphonic ensemble at Carnegie Hall.

- The time Jessye sang both Cassandra

and

Dido in the same performance of

Les Troyens

at the Met. - The concert of Spirituals, with Kathleen Battle at Carnegie Hall.

- Strauss’s

Vier letzte Lieder

and Wagner’s

Wesendonck Lieder

on the same program with the Berlin Philharmonic. - The rehearsals, performances, and recording sessions for Schoenberg’s

Erwartung. - The recording sessions for

Die Walküre, Parsifal,

and songs of Beethoven, Wolf, Debussy, and Schoenberg. - Lots of recitals, especially in Vienna, Salzburg, Chicago, and New York—and the unique Songbook series at Carnegie Hall.

Over the years at the Met, I was lucky to work with Jessye in dozens of exciting rehearsals and performances, starting with her unforgettable debut in

Les Troyens

on the opening night of the Metropolitan’s one hundredth anniversary season. The excitement never flagged as she gradually built her singular Met repertoire:

Die Walküre, Parsifal, Tannhäuser, Erwartung, Bluebeard’s Castle, Oedipus Rex, Ariadne auf Naxos, The Dialogues of the Carmelites, The Makropolus Case

. . .

The book you hold in your hands is Jessye’s latest work of art. Not a career chronicle like so many (“and then I did . . .”) but the story of her magnificent life written in her own words—not the words of a “ghostwriter,” and, of course, in her own voice as well. Her mastery of language goes hand-in-glove with her mastery of music and singing, and her work ethic is ideal! Would that it were a model for every singer.

In this fascinating memoir, you will feel Jessye’s unique presence on every page—her passion, her sense of humor, and her full-scale zest for life. I recommend it as a “must-read,” not only for her legion of admirers but also for the layman, for students of every age—everyone who cares about the artistic life.

James Levine

New York City

February 2014

Prelude

It was a beautiful autumn when I found myself in Europe for the very first time, in bustling, stylish Munich. While completing a master’s degree in vocal performance at the University of Michigan, I had been among the students selected from around the country by a special committee of the United States Information Agency to participate in international music competitions. I was thrilled to be taking part in the prestigious Bayerischer Rundfunk Internationaler Musikwettbewerb, the Bavarian Radio International Music Competition. Julius, a great friend and fine pianist whom I knew from my undergraduate days at Howard University, had traveled with me as my accompanist. There was electricity in the air: the whole city seemed to be involved in the events at the Bavarian Radio. All of the performances during the competition were to be held before a live audience.

The country Julius and I had left behind for these few weeks was on fire. The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the previous spring had sparked riots all over the States. Classes at Berkeley had not taken place in months. Los Angeles, Detroit, and Newark were ablaze with the passion for peace and justice. Protesters marched, organized sit-ins, and took over administration buildings on college campuses. Attacks on Dr. King’s legacy were as vicious as the trained-to-kill dogs, fire hoses, and smoke bombs directed at American citizens exercising their civil rights. Those sworn to protect and serve stood quietly on the sidelines or, worse still, joined the chorus of hate emanating from those sidelines.

The war in Vietnam had surely and steadily lost support, and no half-truths or presidential speeches beginning with the words “My fellow Americans” could douse the flames of revolution visible just across the street from the White House, in Lafayette Square. The country roared in opposition to the status quo. Europe was no less a hot spot, particularly in Paris, where student protests against university tuition payments and other concerns made for significant unrest. The world was most certainly in a state of evolution and revolution.

I had participated in mass meetings and protest marches, carrying signs exhorting

NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE,

and lending my voice to the song concluding almost every gathering, Pete Seeger’s “We Shall Overcome.” I understood that many organizations, with varying approaches to the fight for justice, were needed. No single civil rights group could channel every frustration, or rally everyone to stand tall in the face of those who would just as soon see us crawl away in defeat. Every voice needed to find its own place, its own platform from which the cry for freedom and equality could be heard.

Even though I was engaged increasingly in politics and social issues back home, I was enthralled by gorgeous Munich, and had few worries about my participation in this important competition. I felt that I was there to offer what I had been trained to do, first at Howard, then the Peabody Conservatory, and now at Michigan, with these very words from my mother in my ears from my earliest memories: stand up straight and sing!

Shortly after our arrival, Julius and I received the time slot for our appearance in the first round of the competition. All was well. Our performance time in hand, we went into a rehearsal room to make our final preparations, mindful of the wonderful honor that had been bestowed on us. Yes, we were here to represent ourselves, but more importantly, we were representing the United States of America in an international forum. We took this to heart.

Julius and I moved through the first round of competition with appreciation for all the work we had put into rehearsing and studying for this moment. We felt compelled to do even more, and work even harder in the next round. This was a serious event and an important time in our young lives, and we were grateful that we felt prepared.

Round Two.

A different kind of electricity surfaced in the second round of competition. Almost as soon as the names of those who had made it to the second round were announced, I was called into a room far away from the performance hall, without my friend Julius. There, the adjudicators of the competition suggested that having my own accompanist in Round One had given me an unfair advantage over the other singers. The fact that some of the other singers were participating with their pianist spouses or their coaches was not part of the discussion.

This was unusual behavior for a jury—and most assuredly against its own rules. Normally, there is absolutely no interaction between an adjudicator and a competitor. I was told that I would need to give up my accompanist and sing with one of the piano accompanists provided by the organizers. I did not know quite what was afoot, but I knew enough to request that the new pianist, Brian Lampert from London, should rehearse with me every single song and aria on my list, before I went forward in Round Two.

In the first round, competitors may make their own choices from the list of music approved at the time of their acceptance into the competition, as long as this does not exceed the performance time limit. In the second round, the jury chooses from that same list what the competitor will perform. In still another unusual move, the adjudicators summoned me a second time to discuss my second-round performance. This time I was advised that the jury wished me to sing something that was not on my previously submitted list of repertoire. To my knowledge, no other contestant was being offered such creative treatment.

Now, I had reviewed the requirements carefully for this competition and knew them by heart. I was therefore very comfortable in stating my case: “I am sure that you are not permitted, according to the rules governing the competition, to ask me to sing anything that is not on my list,” I said. “And why would you want me to sing something I have not prepared, in any case?”

“Well,” one judge said, “you have performed the second aria of Elisabeth in

Tannhäuser

during the first round. We would like to hear you sing the first aria.” I stated that I of course knew the first aria as well, but that my vocal professor and I felt that the first aria did not lend itself as a performance piece with piano nearly as well as with an orchestra. That was why this aria was not on my list.