Spirit of the Place (9781101617021) (17 page)

Read Spirit of the Place (9781101617021) Online

Authors: Samuel Shem

After what Miranda called “the shortest bath in history,” Cray was back down at the TV. He popped in the cassette and sat an inch from the screen and yelled back over his shoulder, “Can I eat in front of the TV?”

“You know the rule.”

“Yeah, but tonight's special 'cause there's a guest.”

“A guest who'd like to have you eat with us, right, Dr. Rose?”

“Yeah, I really would,” he said loudly so Cray could hear. “Call me Orvy.”

“But, Mo-om, that's

why

I wanna eat in front of the TV!”

Miranda looked at Orville and shrugged. “Okay.”

Cray shouted, “Yes!” and became silent and still, but for his eyes.

At dinner they talked relaxedly about anything but themselves and their probable love, spending much too long on Hendrick Hudson.

“His name isn't Hendrick but Henry,” she said. “He's English, not Dutch. He sails not under the flag of England but for the Dutch East India Company. The trip here is a disaster. He's trying to reach the Spice Islands. First, he sails in the exact wrong direction, due north up the coast of Norway. The ship freezes. The crew mutinies. He turns back and sails in another exactly wrong direction, west across the Atlantic, and finds the mouth of this river, thinking it will lead to something called the Furious Overfall, and then to the Spice Islands. The Overfall, of course, is a total lie, a fantasy made up by a British explorer named Davies.”

“I love the way you do that,” Orville said. “How you always tell the past in the present tense.”

“Oh. Maybe because the present is so tense sometimes. History's easier for me.”

“For me, too, ever since I met you.”

She blushed. “Colonel Staats, a surgeon and fur traderâ” Their eyes met and she laughed. “Colonel fur traderâ” Again, they blushed and laughed. “Oh, fuck Colonel Staats!”

“No, no,” Orville said, in mock seriousness. “Colonel Staats is crucial.” She grinned, dimpling her cheeks. “So, does Henry Hudson really land here?”

“How do you mean, âreally'?”

“I mean, is it true, then, that he lands here?”

“You think that there exists a âtrue' history?”

“Sure.”

“Oh. Well. When I teach history, in my first lesson I ask the class to write down a sentence describing the weather that day. I write down my own sentence. I read a few of theirs out loud. They're all accurate descriptions: âIt was a sunny day,' or âThe sun shone all day long.' Then I take out my description, âThe day was dark, filled with incessant, driving rain.' I hold mine up to them and say, â

This

is the one that will survive.'”

“So there's no true history?”

“The little histories can't help but be true.”

“Little histories?”

“Of people like us.”

“Ah,” he said, nodding. “Little people like us, yes.”

Looking at him, she got flustered, and brought in of all people Tolstoy. “If you believe Tolstoy, the big historyâsingularâthe one that's written down in books and called âhistory' is at heart a few crucial little ones. When someone asked Napoleon how he chose his generals, he said, âI choose the lucky ones.' Apocryphal, but still.”

“Sounds good to me, Miranda.” The use of her name felt intimate. The glow and scent of the wood fire, the glow of the white wine, the first real easing of worry about how each appeared to the otherâit was sensual, even sexy. They sat and talked for a long time.

“

Look for the bare necessities, the simple bare necessities, forget about your worries and your strifeâyeah, man!”

interrupted the video from the next room.

Miranda watched Orville turn to look. He clearly was not used to having a child around, to attending to two or three or ten things all at once.

Orville was of two minds. He wanted to make contact with Cray but at the same time wanted Cray to evaporate for a while so he could take Miranda in his arms.

“I'd like to try again with Cray,” he said.

“Fine.” She got up, feeling a little tipsy from the wine. “Let's make a little sally into Cray Country.”

Cray was still frozen by the set, a few inches from the screen. A forkful of pasta was in his hand, a plateful on his lap. His straight red hair shone.

Orville made several attempts to engage Cray, starting with, “Hi, Cray.”

Nothing. The boy wouldn't even look at him.

Miranda watched this, saw in Orville the clumsy overtrying of a man who never had children. She felt both sorry for him and more loving toward him for that lack. She touched his arm and said, “It's okay. Let it go.”

But Orville persisted. He himself loved Disney's

Jungle Book,

having watched it years ago when he'd babysat Amy. His favorite animals were the elephants. At one point the elephant leader, Colonel Hahti, does something stupid with his own son, the littlest and last elephant in line, and the colonel's wife, Winifred, confronts him. Orville knew the line by heart, and recited Winifred's line along with her, mimicking exactly her voice, that of a stern old Victorian matron, “

Oh shut up, you pompous old windbag!

”

“Shhh!” Cray hissed. “Now you made me miss it!” He hit Stop, Rewind, Play.

Miranda held out her hand to Orville and led him away, out of the reach of the TV.

“Bye, Cray,” Orville said airily.

Nothing.

“Well, that was a big success,” Orville said.

“Join the crowd. It's almost nine thirty. He and I are gearing up for what I've labeled âThe Nightly War of the Bedtime.'” They laughed. “He's a night owl. He'd stay up until midnight if I let him. Lately it's a real struggle to put him down.”

“I'd like to stay, but with Bill gone, I've still got to make rounds at the hospital.”

“Some other time.”

“I don't meanâ”

“I do.”

He understood and took her hand. “Is it that he doesn't like me? Or is afraid of me? Or just doesn't care?”

“I would guessâand it's just a guess, mind youâthat he's afraid to care, 'cause he might just care too much.”

Orville sighed, relieved. “Yeah, like us all.” He squeezed her hand, feeling sad, sad to leave her, the boy, this cluttered coziness.

Saying good-bye on the doorstep, out of sight of Cray, they hugged. At first it was a we're-adrift-together-in-a-life-raft kind of hug, but then the physical space turned more friendly and they really hugged, he feeling her breasts against his sweater, she feeling his fingers on her back, then tracing light whorls on the nape of her neck, like phantom hair. Standing together out on the cold shelf of winter, just behind the boy's back, it felt illicit, sexy.

“Maybe I could stay?” Orville said.

“You will sometime.” Turned on, she shiveredâand then doubted. “Won't you?”

“Yes.”

· 13 ·

Howdy, partner,

Boca's great. Babs shops & we play bridge with a nice couple Wolfgang and Kenni Vista from Altoona, PA. (“If God'd wanted to give America an enema,” Wolfy says, “he'd stick it in Altoona.”) They're starting a trip around the world. Weather great. Starbusol working even at low doses. Be back a little later than planned. Keep the good virgins of Columbia happyâall three of 'em. Heh heh.

Yr frnd, Bill

This oversized postcard, picturing on the obverse side a glorious sunset framed by a palm tree swooping up from a beach like an exhaust trail from an exploding missile, was dated December 17. It had arrived the day before Christmas. When Bill's expected date of return to Columbia had passed, Orville tried to call him. There was never an answer at the condo. Liberated from caring for the Columbians, Bill had no need for an answering machine.

The troubling thing for Orville was that Bill had mentioned no clear date for his return. And Orville was superstitious about dates. December 17 was a particularly auspicious one: at exactly 10:35

A.M.

on Thursday, December 17, 1903, at Kill Devil Hill, Kittyhawk, North Carolina, Orville Wright took man's first flight, 120 feet in twelve seconds. Bill writing on the eightieth anniversary of this great day for mankind seemed ominous to the other Orville now. Even the headline in

The Columbia Crier

â

BOARD TO DEBATE CHICKENS AT KINDERHOOK LAKE

âcouldn't cheer him up. His thought? Don't bet against the chickens. But who cared. He was in love.

Despite the holiday-season carnage in Orville's practice, he and Miranda were seeing each other as often as possible. They told each other their life storiesâthe censored versions that you tell to non-first loves. He told her about Lily and the hamsterâthe scientific proof of his sterility. He said nothing about his conversations with his floating mother and nothing more about Celestina, whom he'd come to realize was also a floater. Ever since the day in the freezing cold outside the library when he'd read Miranda a piece of a Selma letter and she'd said it didn't seem all that bad, he'd known that it would be a mistake to talk to Miranda about Selma at all. Lily had always despised Selma and maintained that one of the reasons their marriage had fallen out of the sky was that Selma was always

there,

always sticking her nose into things, trying to control them. After seeing Miranda's reaction to the letter, Orville vowed never again to let Selma into this love affair. He promised himself that he'd never talk about her, never even tell Miranda when he had gotten another one of Selma's letters. In his mind there was now a big

KEEP OUT MOM

sign on the door. Selma would be his secret.

Miranda told him about her tragedy with her daredevil husband and about her move up to Columbia from Boca Raton. But she never talked about her polio and kept everything to do with Selma a secretânot only the letters but also how Selma had told her what a “saint” her son had been, staying by her side during that long summer of her hellish disfigurement and recuperation. As Orville and she got closer, each time she sneaked into Columbia to mail a new Selma letter, she felt a little strange. But what could she do? It was, after all, a good deed. While she thought it strange that he never again mentioned his mother, that was okay, tooâit kept Selma out of it.

Every time they had been together, Cray had been with them. Orville's

Hi, Cray

s were still met with silence and downward glances. Now, on Christmas Day as Orville drove out to Miranda's with Amy to exchange presents, he felt a sense of relief. He'd gotten coverage from a local surgeon until midnight, trading Christmas Day for New Year's Day, and Miranda had arranged a sleepover for Cray at Maxie Schooner's. Finally they would have time alone.

As the weeks went by, Miranda struggled with the romance. There was a physical fire between them, and she loved the way that, despite his shyness and doctor's cynicism, he had a remarkable energy, a real interest in and responsiveness to her, and to history, big and little. But with the blossoming attraction came doubt. Over and over she would hear a small voice inside saying, I doubt it, I doubt it. The doubt was about whether or not he was sincere, and about why he never brought up the fact that he was leaving in August. She knew from her past the risk of doubt, how her doubt isolated her from the person she doubted, from the person's world, from the world itself. It had happened with her husband, from their first meeting at the Gasparilla Inn on Boca Grande. He had courted her, reassured her. She resisted. Finally she had let go of her doubt. But now she was alone. In the four years since his death, she'd come to see that when he promised to stay safe for her and Cray, he lied. Stunt flying,

safe?

With Orville she felt she couldn't just jump in. The voice inside kept saying, He's leaving, right? The cost isn't just to you but to your son. Eventually Cray will respond and say hi to him. Once you say hello, you face the terror of saying good-bye.

When Orville and Amy arrived that Christmas afternoon, Miranda felt a surge of happiness. “I'm so glad you came, Amy,” she said. “You must be nervous about tonight, opening night and all?”

“Not really. Greenie Sellers says that if something goes wrong, it's right, and if it's too right, it's all wrong. Shakespeare's text doesn't countâ'cause it's postmodern.”

“Poor Shakespeare!” Miranda said. “This is my son, Cray. Cray, this is Amy.”

“Hi, Cray. What a wicked good tree! My parents don't believe in Christmas.”

“They don't?” Cray asked, his eyes wide. “What are they, Grinches?”

“Jewish. We can't even like utter the name . . . um . . . Jesus Christ.”

“But Jesus was Jewish, right, Mom?”

“Until he converted, yes.”

“This is so neat, Uncle O. My first-ever Christmas. Show me

everything,

Cray!”

Miranda was delighted. Over the past several Sundays spent with Amy working for the Worth, Miranda had fallen a little in love with her. And Amy had responded to her with the full force of an eleven-year-old going on sixteen who's found an alternative to her mother. She told Orville, “Mom and Miranda are like two different species!”

The presents were presented. Orville gave Miranda a pendant on a gold chain, a gold whale with a diamond eye. She gave him a facsimile of a Shaker book published in New Lebanon in 1823,

Gentle Manners: A Guide to Good Morals.

Amy thought this a riot, snatching it and reading aloud in her stage voice a passage about “Life as a Moral Essay” and also from “Sixty Rules of Civility,” by General George Washington.

“Scoff at none,” she read archly, “though they give occasion.”

“Scoff at none,” Cray mimicked. “Scoff at none! Yuck!”

“And listen to this!” Amy said, turning to the inside cover. “To Dr. Rose, in gratitude for your gentleness walking with me in love. . . . Uh-oh. . . .” Amy stopped, mortified. “Sorry. It's personal, right?”

“It's okay, Amy dear,” Miranda said, blushing. “Here's your gift from us.” A first edition of Stanislavsky, Volume 1:

On Acting.

Amy squealed in delight and clasped it to her heart theatrically. Orville gave Cray a video of

Jungle Book,

“to keep for your own.”

They sang a few carols and drank some mulled cider, and then it was time for all of them to go, Amy to the theater and Cray to the Schooners'. Cray gathered up his sleepover necessitiesâclothes and a teddy and a

Babar

and the

Jungle Book

video. He hoisted his backpack and a smaller wicker basket shaped like a duck. As they were putting on coats and boots, he pushed Miranda forward toward Orville, hiding behind her.

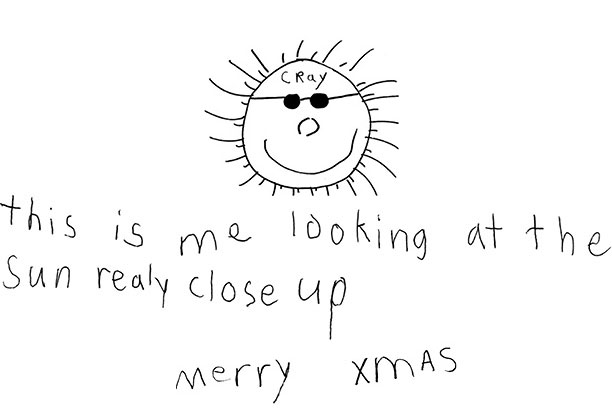

“Go on, Cray,” Miranda said. “You give it to him yourself.” Cray vehemently shook his head. “But it's from you, not me.” Another no. “Okay.” She handed Orville a card.

“Hey, thanks, Cray. It's beautiful. I love it very much.”

Cray said nothing. But then he peeked from behind Miranda's pants and for a split second made eye contact with Orville, who was so touched that he made sure not to show any sign of it, so as not to scare the boy off. Miranda felt joy, then doubt, but was left leaning toward joy.

Later that evening, as Miranda and Orville walked together down the aisle of the decaying Opera House on lower Washington, they created a stir. They were together in public for the first time. Penny waved them over to sit with her and Milt, greeting both of them warmly. Milt greeted them coolly.

“Unreal,” Penny whispered to Orville. “Amazing!”

“What?” he whispered back.

“Maybe you're getting

socialized!

Mom said she'd die before she saw it, and she did. But I always said all it would take was the right girl.”

“I thought you said Miranda's the wrong girl.”

“To Milt, yes. Me, I'm agnostic. And heyâFaith Schenckberg she's not.”

As the lights started to fall, the Schooners enteredâgrandly, smiling and waving. Both looked gorgeous, Henry in his crisp white naval officer's dress uniform and Nelda Jo in a silky red gown suspended by spaghetti straps, making her seem, to Orville, a live advertisement for whatever she ate or drank or did aerobics to or had surgery on. And was it patriotism or lust, he wondered, astir in the pants of the sturdy men of Columbia? The Schooners smiled deeply at each other, as if they'd just that day fallen in love.

Miranda bent forward and talked across Orville's lap to Penny. “Don't you feel great when you see two people smiling at each other like that?”

Penny thought hard about this. “No,” she said, matter-of-factly. “I

feel great when they both turn and smile at

me.

”

The lights went out.

A Midsummer Night's Dream

went on. Sort of. The Fairies were Hell's Angels, the Lovers were Kabukis, the Rustics were gay. The play was cut severely, and it was hard to understand who was who and what was what.

But Amy was game, playing the Queen of the Fairies, Titania. She was the only child in the play, and Orville was touched to see her stand up so bravely and sweetly in front of the crowd. She seemed to have a natural flair and voice for it. When Titania caressed Bottom (dressed as an ass), somehow the innocent sincerity of her voice and her linesâfor who of us, Orville thought, has not been fooled in love?âbrought a hush to the audience.

“Sleep thou, and I will wind thee in my arms.

Fairies be gone, and be all ways away.

So doth the woodbine the sweet honeysuckle

Gently entwist; the female ivy so

Enrings the barky fingers of the elm.

O, how I love thee! How I dote on thee!”

Miranda, holding Orville's hand, caressed it, and snuggled into his neck.

At that tender moment, however, the action shifted to a biker entering on a real Harley, and the rest of the spectacle left the audience puzzled and disgusted.

But then the New York antique dealers “got it.” A murmur sped through the crowd: “It's all a jokeâon

us!”

The play lasted forty-two minutes, which seemed to Orville and Miranda more like two hours. The New Yorkers leapt to their feet for a standing ovation.

Milt said to Orville, “Forty bucks an hour to that fucked-up dwarf Greenie Sellers for lessons in royal bullshit like

this?

”

In the receiving line, Amy asked them, “How'd you like it?” Orville and Miranda said that both the play and she were great.

“Yeah?

Really?

”

“Really,” Orville said. Miranda nodded.

“Cool! And did ya hear? They're talking about taking it to New York!”

Orville shook the tiny Sellers's hand. He'd known Greenie as a boy, a misfit sent by his rich parents to prep school in Tokyo, and from his officeâa man expert in phantom complaints, but for a menagerie of veneria to make a profligate Venetian proud.