Spain (9 page)

Authors: Jan Morris

For Spain is full of hardshipâdo not be deceived by the smiles, the elegant clothes, the ubiquitous aerials and the slum clearance. Men of the Spanish bourgeoisie, teachers, bureaucrats, or army officers, often have two separate jobs to make ends meet, and even the overwhelming love of children that is so characteristic of Spanish life stems partly from the fear of poverty, for one day those boys and girls, so prettily indulged today, will have to support their aged parents. There is no more heart-rending experience than to spend a morning with a team of Spanish sardine fishermen on a bad day; they work like slaves, wading into the sea with their huge net, laboriously hauling it, inch by inch, hour by hour, up the sands: so much depends upon that catch, so much labour and good humour has been expended, so courteous are those men to one another, so many hungry children are waiting to be fed at homeâand when at last the catch appears, a dozen small fish in the mesh of the net, a sensation of hopeless resignation seems to fall upon the beach, and the fishermen, carefully clearing up their tackle, separate to their homes in weary silence.

All this you may sense most pungently in Andalusia, if you get off the main roads and keep your reactions sharpened. The worst is over now, as modernity creeps into the south; down on the coast the glittering blocks of the tourist towns are very symbols of change and chance; but this is a country only just escaping from indigence, and there are abject corners still. Only within the last couple of decades have Andalusian country people been introduced to running water, lavatories, domestic electricity, tractors. Many village streets are still made of earthâcloudy dust in the summer, impassable when the rains fall. In thousands of village houses cocks, goats and even pigs share living quarters with the owners. The children look much healthier nowadays, but the last generation's poverty is everywhere to be seenâwomen aged beyond their years, men mis-shapen, blind or mindless.

Sometimes even now this poverty is so primitive that you have to rub your eyes or blink to make sure that you are in Europe at

all. The cave-dwellings of Andalusia, for instance, though generally comfortable enough, are sometimes little more than burrows: if you wander through the great cave-city of Guadix, east of Granada, which rises like a huge warren among the hills above the town, you will find that the lower caves are nicely whitewashed and pleasantly furnished, lit by electric light, with bright curtains at their entrances, flowers on their trellises, and demure women sewing at the tables of their little patios. Go further up the hill, though, through the maze of lanes and cave-terraces, and presently you will find those tunnels getting dirtier, and darker, and crumblier, and more lair-like, until at last, in the ashen slopes high above the town, some wild covey of slum children will come swooping out of a crack in the ground, so wolfish, swift and swart that you will turn on your heels instinctively, and fall headlong down the hill again.

And most elemental of all are the strange thatched huts, more haystacks than houses, that you still see here and there in Andalusia, like kraals in the African veldt. I was once most kindly entertained in one of these homesteadsâa pair of huts, side by side, with living quarters in one and sleeping quarters in the other. Nothing could be simpler, or much nearer the lives of our neolithic forebears. An open fire burnt in the centre of the living hut, and everything inside seemed charred or blackened with smoke. The hut-people had no beds to sleep on, only a pile of blankets; they had no schools to go to; they lived, so far as I could make out, on soup and bread; and when I stumbled over a sack upon the ground, I heard a faint but testy squeak beneath my feet, and discovered that it contained a small black pig. Those Spaniards possessed, I think, not one single inessentialânot a picture, not an ornament, not even a ribbon for the hair. They could not read, they had no wireless, and they had never seen a city. They were, as nearly as a European human can be in the twentieth century, animals.

But animals of dignity. I asked the father of the family if he liked his way of life, and his only complaint was the inflammability of the hutsâthey were

always

burning down, he said. The Spaniard bears his poverty without much grievance, so that

the visitor, overwhelmed by the flourish of it all, scarcely notices how poor the people are. Indeed, life is undeniably improving, as modernity creeps in: most villages have electric street lighting nowadays, and there can hardly be a row of houses in Spain that does not possess a television. Your conscience will not always niggle you, as you wander through Andalusia. It is a tactful kind of Paradise. You will be able to convince yourself, easily enough, that half the poor prefer to be poor, and the other half won't be poor much longer.

For one must admit that the earthiness of Spain, which is the cousin of backwardness, is often very beautiful to experience. One of the glories of Spain is her bread, which the Romans remarked upon a thousand years ago, and which is said to be so good because the corn is left to the last possible moment to ripen upon the stalk. It is the best bread I know, and its coarse, strong, springy substance epitomizes all that is admirable about Spanish simplicity. It is rough indeed, and unrefined, but feels full of life; and poor Spain too, as you may see her in Andalusia, seems crude but richly organic. Some of her vast landscapes have still never felt the tread of a tractor. All has been tilled by hand, and all still feels ordered and graceful, the energies of the earth rising in logical gradation through ear of corn or trunk of olive into the walls and crowning towers of the villages, sprouting themselves like outcrops of rock from the soil. Spain is a hierarchal country: on the farm, from the grave old paterfamilias at one end to the turnips in the field at the other; in the nation, from the grandees of Church and State, the brilliant young men at the Feria, or the debutantes showing their knees in the noisy sports cars of Madrid, to those simple people of the thatched huts, with their huddle of blankets on the earth floor, and their piglets in sacks beside the fire. It may not be just, the

sol y sombra

, it is inevitably changing, but it feels all too natural: just as the bread, though it may lack finesse, certainly fills you up.

Cante jondo

, I observed a few pages back, is part Oriental, part Gregorian, part Moorish, part Jewish, and is best sung by gypsies. I was, however, oversimplifying. Some authorities detect Phoenician origins in this archetypically Spanish music. Some fancy echoes of Byzantine liturgy. Some hear the rhythms of the African Negroes, and some castanets of Troy. There never was such a palimpsest as Spain, so layered with alien influences. From the tiers of the Roman amphitheatre at Sagunto, the

casus belli

of the Second Punic War, you may see the memorials of five different cultures: in the hillside above, the holes of the Iberian troglodytes; in the country around, the vines of the Greeks; beneath your feet, the Roman paving-stones; behind your back, a rambling Moorish castle; and away at the water's edge, the tall black chimneys of a blast furnace. Spain is the most militantly insular of States, but she is trodden all over with foreign footsteps.

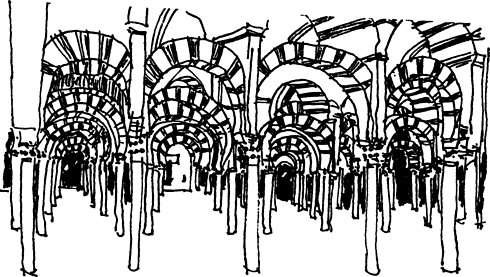

How much is Moorish in the national temperament, and how much indigenous Iberian, the experts seem unable to decide; but there are moments, when the harshness of Spanish life feels

particularly oppressive, when one is tempted to call everything abrasive Iberian, and everything lubricant Moorish. Certainly there are nagging undertones of regret to the greatest of the Islamic monuments of Spain, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, for now that its mihrab has been demoted to be a mere curiosity, its courtyard taken in hand by the canons, its huge martial expanse blocked by the Christian altars in the middle, its old brotherly arcades walled in, its ablution fountains converted to ornamental pools, and its wandering sages banished for ever from the orange treesânow that it has been Christianized for seven hundred years, it feels a marvel

manqué

, a Dome of the Rock drained of its lofty magic, or a Kaaba removed from Mecca. It is only lately, under the example of foreigners, that the Spaniards have really recognized the Moorish genuisâUnamuno, indeed, thought the Moorish conquest the supreme calamity of Spain. The Alhambra was used by the conquering Christians as a debtor's asylum, a hospital, a prison, and a munitions dump, and it is only in our own times that they have placed upon the ramparts of that golden fortress the haunting appeal of De Icaza's blind beggar:

Dale Limosna, Mujer

,

Que no hay en la vida nade

Come la pena de sex

Ciego

en Granada

.

Â

Alms, lady, alms! For there

Â

is nothing crueler in life

than to be blind in Granada

.

The last Moriscos, or Christianized Moors, were expelled from Spain in 1609, but all over this country you will see people in whom the Moorish blood still runsâswarthy, skinny men built for the burnous, women whose eyes peer at you obliquely out of narrow windows, scampering small boys like Kasbah urchins, old men with fringed beards like marabouts. There are no longer, as there were before the Civil War, women in the south who veil their faces like Muslims; but time and again, when some old

village lady wanders into the grocery store and spots a stranger there, you will notice that she takes the corner of her black headscarf between her teeth, and holds it there defensivelyâprecisely as the women of Egypt, midway between purdah and emancipation, half veil themselves in reflex. The Spaniards do not ride their donkeys in the rump-seated Arab manner (though the Spanish knights of the tourneys did adopt the short stirrup of the Moors); close your eyes one day, all the same, when some blithe donkey-man is passing your window, and as the neat little clip-clop of his hoofs echoes down the street, and as the man hums, half beneath his breath, some complex quarter-tone refrain, you may almost think yourself in Muscat or Aqaba, watching a portly merchant of the suk plodding through the palm groves.

The timeless quality of Spanish life still feels very Muslim: at the frontier with Andorra, any hot weekend, a Spanish frontier official sits on a kitchen chair in the sunshine to examine the passports, and looks so thoroughly pasha-like, with his papers and his paunch, that you actually notice the absence of his hubble-bubble. The Spanish talent for enjoyment sometimes reminds me of the Arab countries: like the Egyptians, the Spaniards love public holidays, public gardens, picnics, lookout towers, rowing incompetently about in boats or trailing in vast family groups through scenic wonders. The deadpan face of Spanish politics sometimes evokes visions of reticent sheikhs, and the Spanish passion for sweet sticky cakes has something to it of houris, harems, and jasmine tea. Now and then the guidebook will tantalizingly observe, of some small village in the Ebro delta, perhaps, or a remote high

pueblo

of Andalusia, that its people âstill preserve certain Moorish customs'; and though the book is never more explicit, and the village, when you reach it, usually seems all too ordinary, still the phrase may suggest to you, in a properly Oriental way, hidden legacies of magic, pederasty, or high living that make the East feel pleasantly at hand.

For the Moorish way of life was not confined to any conquering elite. The Moors impregnated the whole of society with their manners, so that even now it is easy to imagine the black tents of the Bedouin pitched, as once they were, around the walls of

Toledo. During the centuries of the occupation, all Spain was bilingualâeven the Christian princes of the north spoke Arabic to each other, and decked themselves in Moorish fineries. The Cid fought sometimes for a Christian faction, sometimes for a Muslim, and throughout the campaigns of the Reconquest there was constant intercourse, if only through the medium of refugees, between one side and the other. Many Christians were converted to Islam. Many more, though they kept their Christian faith under Moorish rule, looked, lived, and probably thought like Moors. The Muslims were rulers in Spain for more than seven centuries, and they dug their roots deep.

There is a place in Granada that well demonstrates how deep. On the hill above the city there stands, of course, the Alhambraâfoppish within, tremendous on the outside, especially if you pick out its red and golden walls through the lens of a distant telescope, and see it standing there beneath the Sierra Nevada like an illumination in a manuscript. The building I have in mind, though, is less grandiose. It stands in the heart of the town below, and to reach it you walk down a small alley beside a bar, and push open a great studded door on the right-hand side. There you will find, tucked away from the traffic, very quiet, very old, a Moorish caravanserai. It is a square arcaded structure, with a stone-flagged court, and its walls are so high that it is usually plunged in shadow. A caretaker family inhabits one corner, and the woman may look out at you from her kitchen window, pushing the hair back from her eyes; but the courtyard itself is nearly always deserted, and feels peopled only by ghosts. Nothing is easier than to see the merchants there, with their baggage-trains and their striped blankets, their hookahs and their towering turbans. Nothing is easier than to hear the racket of their bargaining, the shouts of the caravan-masters and the grunts of their animals, the liquid flow of Arabic among the elders squatting beneath the arcade, or the lovely intonation of the Koran from some blind beggar beside the gate.

And when you leave the place, to pop into the bar, perhaps, for a glass of wine and a plate of prawns, unexpectedly you will find that the ghosts have come with you, that the man behind the bar

looks, now you think of it, remarkably like a Yemeni, and the hubbub of voices in the saloon behind your back is not at all unlike the haggle of a Syrian bazaar. It was not long ago. It is not far away. You can often see the houses of Morocco from the hills above Gibraltar, and Spain still possesses two enclaves, Ceuta and Melilla, over there on the Maghreb shore. In the Alpujarra mountains the godmother, returning the child to its parents after a christening, still says: âHere is your child: you gave him to me a Moor, I hand him back a Christian.' When in 1936 the Nationalists besieged in the Toledo Alcazar were relieved at last by Franco's Army of Africa, they knew their ordeal was over because, listening through their battered walls to the noise of the streets outside, they heard the Moroccan infantry talking Arabic.

I was once loitering though Cádiz, that old white seaport on a spit, when I came across a boy and a girl playing soldiers. The girl was dressed as a knight-at-armsâcardboard helmet, broad-edged wooden sword, a plastic shield from the toyshop and a grubby white nightgown. The boy was unmistakably a Moor, with a floppy towel-turban precariously wound around his head, and a robe apparently stitched together of old dusters. I asked each of them, as a matter of form, whom they represented. âI am the Christian

caballero

,' said the girl brightly, hitching her helmet up. The boy, however, had more sense of history. â

I am the others!

' he darkly replied, and bent his scimitar between his hands.

Nor were the Moors the only Orientals to bring a tang or a smoulder to Spainâitself a country, for all its brackish magnificence, that sometimes seems short of salt. It is almost five hundred years since the Jews were expelled from Spain, but even now you often feel their presenceâshadowy, muted, but pervasive still.

Their position in Spanish society, before their expulsion (or conversion) in 1492, fluctuated from ignominy to near-supremacy. The Visigoths often treated them abominablyâunder King Erwig, for instance, their hair was cropped, their property was confiscated, their evidence was not acceptable in a court of law,

and they were given a year to recant their faith. Under the Muslims, on the other hand, they thrivedâit was partly Jewish help that enabled the Moors to occupy Spain so swiftly. Beneath the tolerant aegis of Islam, for three centuries they enjoyed their golden age: rich, honoured, cultivated, influential. There were towns in Spain that were entirely Jewish, and even Granada was known as the City of Jews. The Jews were the doctors of Moorish Spain, the philosophers, occasionally the diplomats, sometimes even the generals. Their own culture flourished as it seldom has in Europe, first in Granada, then in Toledo, and a reputation of almost Satanic ability surrounded their affairs. âPriests go to Paris for their studies,' it used to be said, âlawyers to Bologna, doctors to Salerno, and

devils to Toledo!

'

In the Christian kingdoms, before the completion of the Reconquest, the Jews intermittently prospered too, and at least among the ruling classes there was nothing pejorative to a Hebrew name. Alfonso VIII of Castile had a Jewish mistress, Pedro I of Aragón had a Jewish treasurer, in the synagogue called El Tránsito in Toledo an inscription on the wall honours, all in one whirl, the God of Israel, King Pedro the Cruel of Castile, and Samuel Levi. There were several Jewish Bishops of Burgos. It was only in the late fourteenth century, when the Reconquest was nearly complete, that the persecutions began againâand even then those Jews who accepted Christianity at first suffered no hardship, and formed indeed almost the whole merchant and banking class. The secret practice of Judaism, however, turned the people against them, and in the end the most devoutly Christian Jew was likely to be suspected of continuing his dreadful practices in private, burning Catholic babies when nobody was looking, or interspersing his Masses with black magic. The afternoon of the Spanish Jews burst into a blood-red sunset. Harassed by the Inquisition, deserted by their patron-kings, burnt in their hundreds, in the very year of the fall of Granada they were expelled

en masse

from Spanish soil. Thus the Catholic Monarchs, at the moment of Spain's greatest opportunity, threw out of their domains several hundred thousand of their most talented, efficient, and necessary subjects.

They went without their possessionsâcapital they could take out, through letters of credit on banks owned by Jews elsewhere, but their libraries, their treasures, their land and their fine houses they left behind. They left their shades in the old Jewish quarters of the cities, from the hill-top ghetto of Toledo to the lovely labyrinth called Santa Cruz in Seville. They left synagogues here and there, converted nowadays into churches or museums, with crumbling friezes of Hebrew script around their walls, and dim memories of great wealth. They left some hints of their extraordinary talents. It is said that the tremendous sculptor Gil de Siloé was a Jew. Some people think Columbus wasâin his will he left âhalf a mark of silver to a Jew who used to live at the gate of the Jewry in Lisbon'. St. Theresa had Jewish origins. There was indeed a time when most men of culture in Spain were Jewish, and such a hegemony cannot easily be expunged; the Jews have left behind them a strain of blood, a look in the eye, that is apparent everywhere in the cities of Spain, and subtly contributes to her grandeur.

For several centuries after the expulsion there were no Jews in Spain at all, except those who had merged undetectably into the Christian whole. They were remembered with distaste. The palace called the Casa de los Picos in Segovia, which is studded all over with diamond-shaped stones, is said to have been faced in this way, after the expulsion, to blot out memories of its former Jewish ownership: till then it had been known as the House of the Jew, now it was the House of Bumps. In many a Spanish cathedral you will find memorials to Christians allegedly murdered by Jewish fanatics, and even today one guide to Seville describes a particular corner of the city as having been âa last outpost of bearded Jews, charlatans, and other queer characters'. A few Jews have come back, all the same. Some returned in the nineteenth century, and some have more recently arrived as refugees from Muslim Morocco. The English cemetery at Málaga is mostly occupied by people like John Mauger, Master of the Schooner

Lady Marsella

, Henry Hutting of the Brig

Dasher

, or William P. Beecher, of New Haven, Connecticut, whose tomb, erected to âcommemorate the merits of his useful life', is embellished with a

mourning figure of Liberty and the thirteen stars of the original Union; tucked away in one corner, though, there is the grave of a solitary Jew, who died in 1961 of the Christian era, or 5721 years after the Creation.